|

|

|

|

|

Initial Cutaneous Metastases of Pancreatic Cancer without Evidence of Pancreatic Mass

|

|

|

|

Priyanka Sunil Patel, Neeharika Srivastava Makani Department of Comprehensive Hematology-Oncology, LLC, St. Petersburg, FL, USA. |

|

|

|

|

|

Corresponding Author:

|

|

Dr Priyanka Sunil Patel Email: priyankapatel1995.12@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received:

01-MAY-2021 |

Accepted:

31-JUL-2021 |

Published Online:

10-SEP-2021 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

|

|

|

|

Background: Pancreatic cancer has high malignant potential and has one of the worst prognosis. Local symptoms are not well defined in pancreatic cancer because it is located in the retroperitoneum and has a thin film. Patients often do not present with the early stages of the disease. Immunohistochemical screening methods assist in diagnosing the primary tumor of origin. Case Report: A 76-year-old male presented with 1-year post laparoscopic para-esophageal hernia repair. He presented with intermittent discharge and nodular thickening around the anterior abdominal wall post-surgery with CT-guided biopsy showing metastatic adenocarcinoma, a PET/CT scan showing no abnormality within the pancreas, CA19-9 elevated, and immunostains suggestive of pancreaticobiliary primary. The patient was treated with FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy, which is the first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer, and he had an excellent response within just two cycles. Conclusion: Cutaneous metastases of pancreatic cancer without any evidence of pancreatic mass is an unusual presentation. Hence full workup including biopsy, immunohistochemical stains, PET/CT scan, serum tumor markers, and additional gastrointestinal workup (EUS, ERCP) is required to evaluate for primary pancreatic mass. |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

Adenocarcinoma, Biopsy, CA-19-9 Antigen, Fluorouracil, Pancreatic Neoplasms.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff2455350000004606000001000900 6go6ckt5b5idvals|3090 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Exocrine pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal malignancy. Annually, in the United States, nearly 57,600 patients are diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic cancer, and almost all are expected to die from the disease. Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States among both men and women. Eighty-five percent of these tumors are adenocarcinomas arising from the ductal epithelium. Pancreatic cancer mainly affects individuals residing in the Western/industrialized parts of the world; the highest incidence is reported in high-income North America, Asia Pacific, and Western and Central Europe, while people living in South Asia and eastern and central Sub-Saharan Africa have the lowest reported incidence [ 1]. Major risk factors for pancreatic cancer are new-onset diabetes after 50, smoking, high body mass index, chronic pancreatitis, and a family history of pancreatic cancer [ 2]. Pancreatic cancer has a high malignant potential and has one of the worst prognosis. The 5-year survival rate for stage 4 pancreatic cancer is approximately 3%. Local symptoms are not well defined in pancreatic cancer because it is located in the retroperitoneum and has a thin film. Thus, patients often do not present with the early stages of the disease [ 3]. Pancreatic cancer cells metastasize initially to the liver and lung and then to relatively slow-growing tissues such as skin, muscle, and bone [ 3]. The pathophysiology of cutaneous metastases of pancreatic cancer is not well described; possible mechanisms responsible for skin metastases in pancreatic cancer are the “soil and seed” hypothesis, which is the seeding of a tumor during resection, chemotaxis hypothesis, which is the spread of cancer cells with high expression of chemokine receptor to the specific sites, direct invasion, lymphatic system, and hematogenous spread [ 4]. Cutaneous metastatic disease has been well-described in both leukemias and other solid malignancies. Any changes in the skin should raise the suspicion of metastatic disease, especially in patients with a history of cancer or those with a high risk of cancer. A biopsy is needed to make the diagnosis. Immunohistochemical screening methods assist in diagnosing the primary tumor of origin. Immunohistochemical findings can also help direct treatment options. There have been improvements in immunohistochemical staining, and now with newer next-generation sequencing, the cell of origin can often be determined. With advances in newer therapies that prolong survival, prompt identification of cutaneous metastases can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality [ 5]. We present the following case report in accordance with the CARE-Guidelines. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Case Report

The patient is a 76-year-old male with a past medical history of para-esophageal hernia, hiatal hernia, atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation, hypothyroidism, male erectile dysfunction, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who presented 1-year post-laparoscopic para-esophageal hernia repair and cholecystectomy. The patient complained of discharge at the umbilical site, which started several weeks after his surgery. This discharge would intermittently improve. Seven months post-surgery, the skin around the umbilicus had developed a 10×5 cm area of denuded skin with maceration with several subcutaneous nodules ranging from 1.5-2 cm [Fig.1]. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis at that time revealed interval formation of nodular thickening within the undersurface of the anterior abdominal wall near the umbilicus and a large area of thickening that measures 1.8 cm in the midline. The other subtle nodules on the abdominal wall’s undersurface were suspicious for a peritoneal metastatic process. A needle core biopsy of the supraumbilical skin lesion was sent to John Hopkins reference laboratories and revealed metastatic adenocarcinoma involving fibrous tissue. The submitted immunostains showed that the adenocarcinoma was positive for CK7 and CDX2 (focal) and negative for CK20, TTF-1, PSA, and PSAP. Immunostains performed at John Hopkins show the adenocarcinoma positive for CDX2, with loss of DPC4 labeling. This immunophenotype was suggestive of spread from a pancreaticobiliary tract primary.

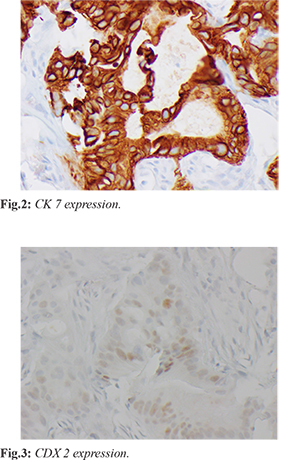

A PET/CT scan was performed and showed abnormal focal uptake in the lower pelvic mesenteric fat and upper left pelvic mesenteric fat. There was also an abnormal uptake in the anterior abdominal wall just above the umbilicus. The patient then underwent a CT-guided omental mass core biopsy, which demonstrated fibro adipose tissue infiltrated by dysplastic columnar glands, which express CK7 [Fig.2] and focal CDX2 [Fig.3] but not CK20, TTF-1, or NKX by immunostains. The immunohistochemical features were not specific to the primary site but favored an upper gastrointestinal (pancreaticobiliary) primary over a lower gastrointestinal tract. The next-generation sequencing assay for the biopsy showed no genomic alteration. The patient was offered additional gastroenterology evaluation with upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasound; however, the patient declined further procedures.

Lab work at time of diagnosis demonstrated a CA 19-9 at 462 U/mL (normal 0-35), CEA at 4.6 ng/mL (normal 0-4.7), and AFP at 2.3 ng/mL (normal 0-8.3). The diagnostic workup with imaging studies, two separate biopsies reviewed by three pathologists, and blood tests were highly suggestive of adenocarcinoma from the pancreaticobiliary source. Patient started treatment with FOLFIRINOX regimen which includes the following: irinotecan 180 mg/m2 on Day 1, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 on Day 1, leucovorin 400 mg/m2 on Day 1, 5-fluorouracil 400 mg/m2 IV bolus on D1 and 5-fluorouracil 2400 mg/m2 over 46 hours continuous infusion via port every 14 days. The patient has thus far received ten cycles of FOLFIRINOX. The patient noted an almost complete resolution of his skin nodules after just two cycles of chemotherapy [Fig.4]. Repeat PET/CT scan following 12 weeks of chemotherapy also demonstrated excellent response to therapy.

Discussion

We describe an unusual case of pancreatic cancer, presenting as cutaneous metastases. The most common site of cutaneous metastasis from the pancreas is the umbilicus, known as Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule. Our case is unique because the non-healing incision site with cutaneous metastases of pancreatic cancer is presented without an actual pancreatic mass. The patient had an interval formation of nodular thickening within the anterior abdominal wall’s undersurface near the umbilicus after his hiatal hernia repair revision. The area was biopsied and showed metastatic adenocarcinoma favoring pancreaticobiliary primary. The patient had two separate biopsies confirming that this adenocarcinoma is likely from a pancreaticobiliary source with an elevated CA19-9 at the time of diagnosis in the 400 range. Patient had a full-body PET/CT scan that showed no abnormality within the pancreas. The patient declined to pursue any additional gastrointestinal workup and was eager to start systemic therapy. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer is rare, often providing the only external indication of internal malignancy. Therefore, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of skin lesions. Cutaneous metastases indicate widespread dissemination and a poor prognosis [ 6]. Cutaneous metastases are seen in 0.7-0.9% of cancer patients. They may be the first manifestation of tumor metastases of an internal malignancy or a cancer recurrence long after treating a primary tumor. Breast, lung, and large intestine are the most common primary sites for skin manifestations of metastatic adenocarcinomas. Less common sites are the stomach, prostate, pancreas, ovary, endometrium, and thyroid [ 5]. Cutaneous metastases commonly originate from breast cancer, melanoma, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer in adult women. It most commonly originates from lung cancer, melanoma, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer in men. In children, they are neuroblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma [ 7]. Brownstein and Helwig classified metastatic cutaneous tumors into three types: nodular, inflammatory, and sclerodermoid; the most common is the nodular type [ 3]. Abdominal cutaneous metastases are common because the tumor cells distributed in the peritoneum metastasize to the umbilicus, adjacent to the epidermis, and can form a nodule, called Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Approximately 44% of the cutaneous metastases from pancreatic cancer are Sister Mary Joseph nodules [ 3]. Determining the primary source of the cutaneous metastasis from an occult tumor is very difficult. However, immunohistochemistry may allow the physician to identify the primary neoplasm precisely [ 8]. Pancreaticobiliary ductal adenocarcinomas have a cytokeratin immunophenotype identical to normal pancreatic ducts, including being positive for CK 7, 8, 18, and 19. Nearly 90% of pancreaticobiliary adenocarcinomas stain diffusely with CK 7 antibody and 50% stain diffusely with CK 19 antibody. Hence, the findings regarding the immunohistochemical expression of CKs are beneficial in diagnosing metastatic carcinomas [ 8]. Immunohistochemistry showed that cytokeratin (CK) 20-negative, and CK7-, CK19- and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9-positive were specific diagnostic markers for pancreatic cancer [ 6]. DPC4 gene is a tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 18q21.1 that mediates the downstream effects of TGF-ß superfamily signaling, resulting in growth inhibition. Inactivation of the DPC4 tumor suppressor gene (deleted in pancreatic carcinoma, locus 4; Smad4) is relatively specific for pancreatic carcinoma. Some studies have suggested that it may even be a molecular prognostic marker for pancreatic carcinoma [ 9]. In our patient, there was a loss of DPC4, again suggesting pancreatic cancer. CDX2 is also an important immunohistochemical stain in diagnosing pancreatic cancer. CDX2 plays a role in inhibiting cell proliferation and repressing cyclin D1 transcriptional activity through the proximal nuclear kB binding site in pancreatic cancer cells [ 10]. More than a third of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas show a weak and heterogeneous expression pattern of CDX2. In comparison, the expression pattern of colorectal lineage is unique and different and shows a strong and uniform expression of CDX2. Thus, when describing the CDX2 staining, most pathologists have to carefully interpret the CDX2 expression pattern instead of just assigning positive and negative expressions. Studies have demonstrated that CDX2 might play essential roles in pancreatic cancer development and oncogenic transformation [ 11]. The biopsies obtained from our patient’s nodules were focally positive for CDX2. Our patient was treated with a regimen commonly used in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. FOLFIRINOX is a regimen consisting of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin is considered the first-line standard of care therapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer patients with good clinical performance status. Studies have shown an improvement in median Progression-Free Survival (PFS) to 6.4 months with FOLFIRINOX compared to 3.3 months with gemcitabine alone with median Overall Survival (OS) from 6.8 months with gemcitabine to 11.1 months with FOLFIRINOX [ 12]. As compared with gemcitabine, FOLFIRINOX was associated with a survival advantage but had increased toxicity [ 13]. Fortunately, our patient has been tolerating the FOLFIRINOX regimen well with minimal toxicity and great response to therapy. The only limitation of our case report is the patient declined a gastrointestinal workup.

Conclusion

We describe a unique case of cutaneous manifestation of metastatic pancreatic cancer without a pancreatic mass. In patients presenting with cutaneous lesions, particularly around the umbilicus area, a biopsy with a comprehensive evaluation of immunohistochemical stains with diagnostic imaging and procedures are required for a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

Contributors: PSP: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work and manuscript drafting; NSM: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. PSP will act as a study guarantor. Both authors approved the final version of this manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of this study. Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References - Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Rahman M, Washington L. The seemingly innocuous presentation of metastatic pancreatic tail cancer: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13:178.

- Ito H, Tajiri T, Hiraiwa S, Sugiyama T, Ito A, Shinma Y, et al. A case of rare cutaneous metastasis from advanced pancreatic cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2020;13:49-54.

- Saif MW, Brennan M, Penney R, Hotchkiss S, Kaley K, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in a patient with pancreatic cancer. Journal of the pancreas. 2011;12:306-308.

- Wong CYB, Helm MA, Kalb RE, Helm TN, Zeitouni NC. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:499-504.

- Zhou H, Wang X, Gao F, BU B, Zhang S, Wang Z. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: A case report and systematic review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Araújo E, Barbosa M, Costa R, Sousa B, Costa V. A first sign not to be missed: Cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001356.

- Jun DW, Lee OY, Park CK, Choi HS, Yoon BC, Lee MH, et al. Cutaneous Metastases of pancreatic carcinoma as a first clinical manifestation. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 2005;20:260-263.

- Hua Z, Zhang YC, Hu XM, Jia ZG. Loss of DPC4 expression and its correlation with clinicopathological parameters in pancreatic carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2764-2767.

- Takahashi K, Hirano F, Matsumoto K, Aso K, Haneda M. Homeobox gene CDX2 inhibits human pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by down-regulating cyclin D1 transcriptional activity. Pancreas. 2009;38:49-57.

- Xiao W, Hong H, Awadallah A, Zhou L, Xin W. Utilization of CDX2 expression in diagnosing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and predicting prognosis. Plos one. 2014;9:e86853.

- Stephane Thibodeau S, Voutsadakis IA. FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of retrospective and phase II studies. J Clin Med. 2018;7:7.

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817-1825.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Google Scholar for

|

|

|

Article Statistics |

|

Patel PS, Makani NSInitial Cutaneous Metastases of Pancreatic Cancer without Evidence of Pancreatic Mass.JCR 2021;11:186-190 |

|

Patel PS, Makani NSInitial Cutaneous Metastases of Pancreatic Cancer without Evidence of Pancreatic Mass.JCR [serial online] 2021[cited 2026 Jan 3];11:186-190. Available from: http://www.casereports.in/articles/11/3/Initial-Cutaneous-Metastases-of-Pancreatic-Cancer-without-Evidence-of-Pancreatic-Mass.html |

|

|

|

|

|