|

|

|

|

|

Pancreaticopleural Fistula: Revisiting a Rare Complication

|

|

|

|

Niket Shah, Naimish Mehta, Vivek Mangla, Romil Jain, Samiran Nundy Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and Liver transplant, Sir Gangaram Hospital, New Delhi. |

|

|

|

|

|

Corresponding Author:

|

|

Dr. Niket Shah Email: nikk240488@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received:

25-DEC-2022 |

Accepted:

06-MAY-2023 |

Published Online:

25-JUN-2023 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

|

|

|

|

Background: Pancreatico-pleural fistula (PPF), a rare complication of pancreatitis, stems from pancreatic duct leakage or pseudocyst rupture. Diagnosis traditionally relies on a triad of pancreatitis history, imaging evidence of pancreatic duct disruption with concurrent pleural effusion, and elevated pleural fluid amylase. While CT has 47-63% sensitivity, MRCP (80%) and ERCP (78%) offer improved visualization and therapeutic potential. Case Reports: Case 1: A 37-year-old male, non-smoker, non-drinker, presented with worsening dyspnea due to left-sided pleural effusion. A 5 mm pancreatico-pleural fistula was found and surgically treated via Roux-en-Y fistulo-jejunostomy, resulting in complete recovery over 5 years. Case 2: A 35-year-old male, chronic smoker and drinker, experienced right-sided chest pain and pleural effusion due to chronic calcific pancreatitis. Frey's procedure, drainage, and fistula division led to symptom resolution, sustained over 4 years. Conclusion: PPF diagnosis combines clinical history, imaging, and pleural fluid analysis. While CT remains useful, MRCP and ERCP provide better sensitivity. Management entails initial conservative approaches, including octreotide infusion, followed by surgery if needed. These cases highlight the importance of early recognition and multidisciplinary care for successful PPF management. |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

Chest Pain, Dyspnea, Pancreatitis, Pancreatectomy, Pleural Effusion.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff64563a0000007a06000001000a00 Introduction

Pancreatic fistula is a rare complication of acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic trauma. It develops because of pancreatic ductal disruption or rupture of a pseudocyst. Pancreatic ascites develops due to free secretion of pancreatic juice into peritoneal cavity. Pancreatico-pleural fistula formation is a very rare complication of chronic pancreatitis and even more rarely seen in acute pancreatitis [ 1, 2]. Its challenging to diagnose this rare complication and even more challenging to treat it adequately [ 3- 5]. Left pleura is the most common location for pancreatic fistula followed by right pleura and both pleural cavities [ 6]. Such exudative pleural effusions can cause chest pain and dyspnoea, like any emergent thoracic pathology e.g., aortic dissection; as a result, this diagnosis is challenging to identify. Pancreaticopleural fistula occurs in 0.4% of patients with acute pancreatitis [ 7, 8], in 4.5% of patients with pancreatic pseudocyst and in 20-30% cases of untreated chronic pancreatitis [ 9, 10]. The pleural effusion associated with pancreaticopleural fistula is typically refractory to drainage and tends to accumulate rapidly [ 7]. Thoracocentesis with measurement of amylase in pleural fluid is the most important diagnostic procedure followed by MRCP or CT for the anatomy of fistulous tract [ 11]. The management is based on three lines of treatment: the first is the conservative medical management which includes suspension of the oral intake, initiation of total parenteral nutrition and administration of somatostatin analogues; the second line is based on endoscopic management by placing a stent in the pancreatic duct, and the third line is the surgical option, consisting of surgical resection (distal pancreatectomy) and enteric shunts (pancreatojejunostomy or cystojejunostomy) [ 12]. In this article, we delve into the clinical narratives of two distinct cases that shine a spotlight on the complexities of pancreatico-pleural fistulas. These cases not only underscore the clinical heterogeneity associated with this condition but also emphasize the importance of a comprehensive evaluation and a patient-tailored therapeutic strategy.

Case Report

Case 1

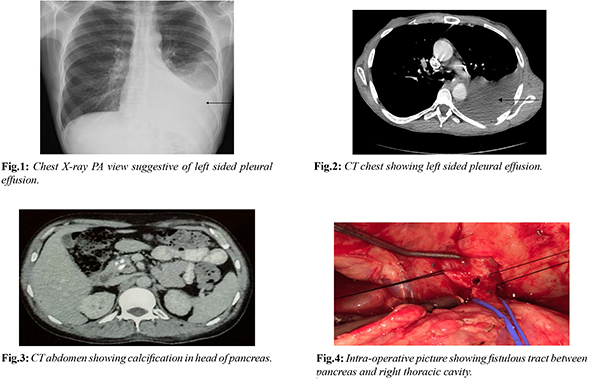

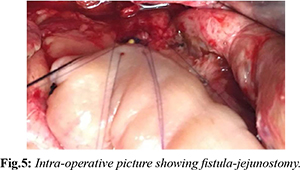

A 37 years old male presented with history of cough with expectoration for 5 months and dyspnea for 3 months which gradually increased over last 4 weeks. Patient was diagnosed to have chronic calcific pancreatitis for 5 years and he was on oral pancreatic enzyme supplementations and oral analgesics for pain relief. Patient was not a smoker and not an alcoholic. Patient was hemodynamically stable and was admitted under thoracic unit. His vital parameters were stable and was maintaining room air saturation 98%. Blood evaluation was unremarkable. His chest X-ray [Fig.1] was suggestive of left sided pleural effusion. Intravenous contrast enhanced CT chest and abdomen [Fig.2,3] showed atrophic pancreas with intra-pancreatic calcification, dilated main pancreatic duct (maximum diameter 10 mm) throughout pancreas and left sided pleural effusion. There was a fistulous tract of size 5 mm diameter and 15 mm length between pancreatic body and left pleural cavity. Left intercostal drainage tube was inserted and the fluid analysis showed high amylase value (25000 U/L). Referral was sought of department of surgical gastroenterology for management of pancreatico-pleural fistula. After thorough counseling about risks and benefits of intervention with family members of the patient, patient underwent laparotomy. Intra-operatively fistulous tract was seen arising from body of pancreas [Fig.4]. Hence division of fistulous tract with Roux-en-Y fistulo-jejunostomy with externalization of anastomotic stent was performed [Fig.5]. Post-operative period was uneventful. Repeat ICD drain fluid amylase was found to be undetected. Patient recovered well and was discharged on day 10 with an anastomotic external stent which was removed after 6 weeks. Patient is doing well on 5 years of follow up.

Case 2

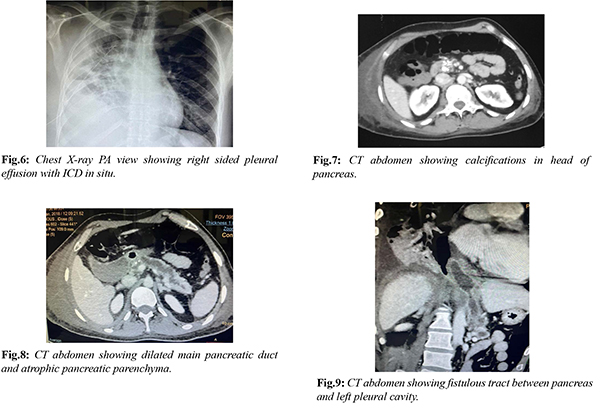

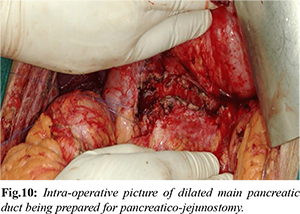

A 35 years old male patient presented with right sided chest pain for 1 month and dyspnea for 1 week. Patient had history of recurrent upper abdominal pain for past 2 years. He was diagnosed to have chronic calcific pancreatitis and was managed conservatively by oral analgesics and pancreatic enzyme supplementation. Patient was a chronic smoker for 10 years and he used to consume alcohol daily for 7 years. Patient was admitted at local hospital where chest X-ray [Fig.6] was suggestive of right sided pleural effusion and hence right sided intercostal drainage tube was placed and he was referred to our center. Patient had stable vital parameters and normal room air saturation on admission. On blood evaluation, patient had severe hypoalbuminemia (1.6 gm/dL) with raised serum amylase (370 U/L) and raised serum lipase (158 U/L). Rest of the laboratory tests were normal. IV contrast enhanced CT chest and abdomen [Fig.7-9] showed calcifications in head of pancreas, dilated MPD, peri-pancreatic region collection without MPD communication and right sided intra-thoracic fistulous extension causing right pleural effusion with collapse of underlying lung parenchyma suggestive of chronic calcific pancreatitis with pancreatico-pleural fistula. Drain fluid amylase was 7522 U/L. After detailed counseling, patient underwent Frey’s procedure [Fig.10], drainage of peri-pancreatic fluid collection and division of fistulous tract. Post-operative period was uneventful and patient recovered well. ICD tube was removed on day 5 once drain fluid analysis showed undetectable amylase level. Patient is doing well on 4 years of follow up.

Discussion

The main pathology underlying these fistulae is a persistent chronic inflammatory process of the pancreas, most often attributed to alcoholic pancreatitis [ 13, 14]. PPF occurs secondary to either pancreatic duct leakage or an incomplete or ruptured pseudocyst, with pancreatic enzymes eroding the fascial planes posteriorly [15,16]. These enzymes erode into the mediastinum via the esophageal or aortic hiatus, resulting into fistula or pseudocyst communicating with the pleural cavity upon rupture [ 16]. An anterior pancreatic disruption is more likely to lead to ascites but can also cause a PPF [ 16, 17]. A hydrothorax more commonly develops on the left but right or bilateral hydrothoraces have been documented [ 15- 17]. The pleural effusion in pancreatic diseases can be either reactionary or pathological due to the fistula. Reactionary effusions are usually small, left-sided (or may be bilateral), with amylase levels <1000 U/L and low protein content <3 g/dL, mostly seen in acute pancreatitis and resolve spontaneously. Effusions due to fistulae are usually large, commonly left-sided, with amylase levels >1000 U/L and high protein content >3 g/dL, mainly seen in pseudocysts and chronic pancreatitis and require intervention for control. A significantly raised pleural fluid amylase is the most important and confirmatory diagnostic test. Acute pancreatitis, pneumonia, malignancy, oesophageal perforation and pulmonary tuberculosis are also associated with raised pleural fluid amylase levels. There is no documented threshold amylase levels in the literature but a level above 50 000 IU/L, is highly suggestive of PPF. Both our patients presented with chest symptoms with high pleural fluid amylase levels i.e. 25,000 U/L and 7522 U/L respectively against a background of chronic pancreatitis suggesting the diagnosis of PPF. The most common symptom of PPF is dyspnoea (65-76%) followed by abdominal pain, cough, chest pain, and fever [16]. These symptoms can be confused for other acute thoracic pathology, making a diagnosis and treatment challenging. Pre-disposing factors include male sex, fifth decade of life, and chronic pancreatitis secondary to alcohol, trauma, and choledocholithiasis [7,10]. The triad of previous pancreatitis, disturbance of the pancreatic duct with pleural effusion on imaging, and pleural exudate showing high amylase levels has been thought to be diagnostic of a pancreatico-pleural fistula [14]. Amylase rich pleural fluid has been documented to be black in color, prompting the consideration of diagnosis of PPF [10,15]. Diagnostic work up includes a chest radiograph followed by a CT scan to evaluate for pancreatitis and associated complications; however, the sensitivity of CT visualization is 47-63% [ 7]. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) allow for advanced visualization and therapeutic intervention respectively with sensitivity of 80% and 78% respectively [ 7, 15]. MRI with MRCP has been found to be superior to ERCP because it provides an image of the whole pancreas as well as a possible pseudocyst. It is also able to delineate the duct of Wirsung distal to the site of obstruction. There are no specific guidelines or approach for PF management because the data is limited. Conservative management with hemodynamic monitoring has resulted in resolution in 30-60% cases [6,16]. Conservative treatment includes complete bowel rest, total parenteral nutrition, and broad-spectrum antibiotics [10]. Octreotide has been used to decrease pancreatic fistula output and reduce the closing time [7]. Both therapeutic and diagnostic, thoracentesis or tube thoracostomy can measure amylase and drain symptomatic pleural effusions [7]. Medical management is usually with octreotide alone used at an initial dosage of 50 mcg TDS increasing to 250 mcg TDS. A long course of treatment for about 2 to 3 weeks is usually required and there is a low success rate of between 30 and 65% as well as needing a longer hospital stay. It is mostly useful in patients without any ductal disruption or obstruction. In the setting of failed medical management or stricture, an ERCP with stent placement or sphincterotomy is warranted [7,10,16]. ERCP can identify the presence of a ductal stricture and the site of ductal disruption. Pancreatic stent placement provides a low resistance path for the flow of pancreatic secretions and allows mechanical closure of the site of the fistula. The duration of therapy and success rate is highly variable. A strategy of repeated ERCP every 6-8 weeks to assess fistula closure has been used by some authors [17]. Conservative management can be successful in patients with pancreatic ductal single stricture with just pancreatic stent placement, whereas patients of multiple strictures, complete duct disruption, large cysts or impacted ductal calculi are managed with surgery. Due to inflammatory reaction around pancreas, retroperitoneal space, large vessels and surrounding organs, surgical interventions can result in severe complications including death. In the early stage of diagnosis, it is advisable to minimize the initial surgery and total excision of the fistula may not be initially possible. The first intervention may involve drainage followed by staged surgeries when the acute inflammation resolves. Goals of management are to restore normal anatomy and decreasing pancreatic secretions leakage, which often requires definitive surgical treatment [7,14,16]. Successful medical conservative management can provide resolution of fistula in 30-60% with a 15% risk of recurrence. Recommended duration of continuing conservative management is 2-3 weeks [7]. Endoscopic therapy with stent placement in the pancreatic duct is used to restore ductal anatomic continuity; it is used in cases of disruption of the pancreatic duct in the body and distal stenosis to the disruption site [7].

Conclusion

A pancreatico-pleural fistula is a rare complication and a challenging diagnosis in patients with chronic pancreatitis and requires thorough evaluation in patients presenting with recurrent respiratory symptoms in the background of pancreatitis. Significantly raised pleural fluid amylase levels with MRCP to delineate the pancreatic ductal anatomy are useful in making the diagnosis and deciding the further management. Conservative medical management by somatostatin analogues and endoscopic stenting have a low success rate and surgical intervention often offers the best chance of cure.

Contributors: NS: manuscript writing, patient management; NM: chief operating surgeon case 1 and manuscript editing; VM: chief operating surgeon case 1 and manuscript editing; RJ: radiological and intraoperative details; SN: critical inputs into the manuscript. NS will act as a study guarantor. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of this study. Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References - Kaye MD. Pleuropulmonary complications of pancreatitis. Thorax. 1968;23(3):297-306.

- Machado NO. Pancreaticopleural fistula: Revisited’, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopy. 2012;815476.

- Kiewiet JJS, Moret M, Blok WL, Gerhards MF, de Wit LT. Two patients with chronic pancreatitis complicated by a pancreaticopleural fistula. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3:36-42.

- Bediwy AS. Pancreatico-pleural fistula: A rare cause of massive right-sided pleural effusion. Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis. 2015;64:149-151.

- Chawla G, Niwas R, Chauhan NK, Dutt N, Yadav T, Jain P. Pancreatic pleural effusion masquerading as right sided tubercular pleural effusion. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease. 2019;89:3.

- King JC, Reber HA, Shiraga S, Hines OJ. Pancreatic-pleural fistula is best managed by early operative intervention. Surgery. 2010;147(1):154-159.

- Aswani Y, Hira P. Pancreaticopleural fistula: a review. JOP. 2015;16(1):90-94.

- Ali T, Srinivasan N, Le V, Chimpiri AR, Tierney WM. Pancreaticopleural fistula. Pancreas. 2009;38(1):e26-31.

- Francisco E, Mendes M, Vale S, Ferreira J. Pancreaticopleural fistula: an unusual complication of pancreatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015:bcr2014208814.

- Hirosawa T, Shimizu T, Isegawa T, Tanabe M. Left pleural effusion caused by pancreaticopleural fistula with a pancreatic pseudocyst; BMJ Case Reports. 2016;bcr2016217175.

- Tay CM, Chang SK. Diagnosis and management of pancreaticopleural fistula. Singapore Med J. 2013;54(4):190-194.

- Olakowski M, Mieczkowska-Palacz H, Olakowska E, Lampe P. Surgical management of pancreaticopleural fistulas. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109(6):735-740.

- Chebli JM, Gaburri PD, de Souza AF, Ornellas AT, Martins Junior EV, Chebli LA, et al. Internal pancreatic fistulas: proposal of a management algorithm based on a case series analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(9):795-800.

- Ong Y, Shelat VG. Ranson score to stratify severity in acute pancreatitis remains valid – Old is gold. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2021;15:865-877.

- Ramahi A, Aburayyan KM, Said Ahmed TS, Rohit V, Taleb M. Pancreaticopleural fistula: A rare presentation and a rare complication. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4984.

- Singh S, Yakubov M, Arya M. The unusual case of dyspnea: a pancreaticopleural fistula. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6(6):1020-1022.

- Akahane T, Kuriyama S, Matsumoto M, Kikuchi E, Kikukawa M, Yoshiji H, et al. Pancreatic pleural effusion with a pancreaticopleural fistula diagnosed by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and cured by somatostatin analogue treatment. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28(1):92-95.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Google Scholar for

|

|

|

Article Statistics |

|

Shah N, Mehta N, Mangla V, Jain R, Nundy SPancreaticopleural Fistula: Revisiting a Rare Complication.JCR 2023;13:63-68 |

|

Shah N, Mehta N, Mangla V, Jain R, Nundy SPancreaticopleural Fistula: Revisiting a Rare Complication.JCR [serial online] 2023[cited 2026 Mar 1];13:63-68. Available from: http://www.casereports.in/articles/13/2/Pancreaticopleural-Fistula.html |

|

|

|

|

|