6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff18dd030000000e02000001000f00

6go6ckt5b5idvals|238

6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Aneurysms of visceral arteries are rare but pseudoaneursyms are even rarer [

1]. They are usually provoked by intrabadominal inflammatory processes such as pancreatitis or cholecystitis or by surgical trauma [

2]. This case report highlights how a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm led to haemobilia which presented as a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and the management undertaken.

Case Report

A 78-year-old male was admitted for functional decline, anorexia and unintentional weight loss of 7 kg over 6 months. He also had occasional abdominal pain and vomiting but no per rectal bleeding or change in bowel habits. He had never had biliary diseases or undergone any biliary tract interventions before. He also had supratherapeutic INR 8.6 (N 2-3) from warfarin. His past history includes atrial fibrillation, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

On examination he was not clinically jaundiced and had no organomegaly or abdominal tenderness. Liver function tests (LFTs) demonstrated an obstructive picture: ALP 426 (N 30-120 IU/L), GGT 284 (N 5-80 IU/L), ALT 112 (N 7-56 IU/L), Total bilirubin 25 (N <20µmol/L). Lipase was 29 (N 12-70 U/L) and white cell count (WCC) elevated at17.9 (N 4-11 x 109/L).

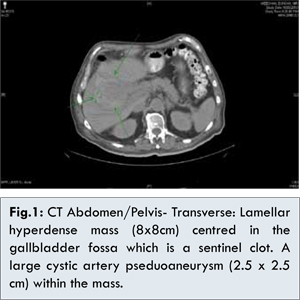

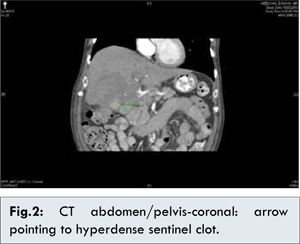

Computed tomography (CT) showed a grossly abnormal gallbladder and a sentinel clot measuring 8x8 cm centred in the GB fossa, invading the liver. Within the mass, there was a large lobulated pseudoaneurysm arising from the right hepatic artery measuring 2.5 x 2.5 cm with no active bleeding [Fig.1,2]. This could have been secondary to infiltration by gallbladder carcinoma or cholecystitis.

The patient became clinically jaundiced during admission with total bilirubin increasing to 60 in 2 days. INR was reversed with Vitamin K to 1.1. Intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole were commenced. His haemoglobin (N 130-180 g/L) also dropped from 104 to 75 with no visible evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding/melena. He then required blood transfusions. He later developed melena with haemoglobin dropping again to 81 over a few days thus requiring further transfusions. He developed right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain. LFTs were still deranged with an obstructive picture and WCC elevated at 16.7. Cancer antigen (CA) 19-9 was markedly elevated at 2144 (N 0-37 U/ml) but carcinoembryonic antigen was normal at 1.2 (N < 2.5 ng/ml). Gastroscopy revealed no active bleeding.

Angiographic platinum coil embolization of the cystic artery pseudoaneursym was then performed [Fig.3,4]. It was uncomplicated as he did not develop cholecystitis secondary to ischaemia and haemoglobin remained stable since then. Therefore, it was haemobilia causing his symptoms.

During follow-up, he was asymptomatic, not clinically jaundiced and had no abdominal tenderness. Surprisingly his CA 19-9 had drastically reduced to 27. His LFTs had dramatically reduced and haemoglobin remained stable. A repeat CT showed improvement in inflammatory changes. Thus, it may have been cholecystitis instead of gallbladder carcinoma that had caused the pseudoaneursym. An elective cholecystectomy was then offered.

Discussion

A pseudoaneurysm is a leakage of arterial blood into the surrounding tissue with a persistent communication between the artery and resultant adjacent cavity. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm can be complication of cholecystitis, cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy induced mechanical or thermal injury [

3,

4]. They manifest as haemobilia when they rupture into the biliary tree. There have been 20 reported cases of this in current literature.

Iatrogenic or traumatic liver injury accounts for approximately half of all cases of haemobilia [

5]. However, major haemobilia is more commonly associated with sepsis and inflammation producing a pseudoaneursym of the hepatic artery [

5]. Typical features of a haemobilia include RUQ abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, gastrointestinal haemorrhaging/ melena (Quincke’s triad) [

1,

6].

Although the detailed mechanism by which acute cholecystitis may lead to a pseudoaneurysm formation is not known, it is thought that with the in?ammatory process, a partial erosion of the serosa, elastic and muscular components of the arterial wall contributes to the pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery [

5]. Visceral inflammation adjacent to the arterial wall damages the adventitia and causes thrombosis of the vaso-vasorum resulting in a localised weakness in the vessel wall [

1,

5]. In addition to acute inflammation, severe damage to the GB wall by a large gallstone eroding into the cystic artery can accelerate the formation of a pseudoaneurysm [

7].

Pseudoaneurysms of the cystic artery are rare possibly because early thrombosis of the cystic artery is considered to be a reaction of the inflammatory process [

8]. However, the pseduoaneursym may have formed in our patient due to his over-anticoagulated state. Cystic artery pseudoaneursyms need to be identified as it can rupture into the peritoneal cavity and cause life threatening bleeding. They can also rupture into the biliary tract causing haemobilia and are a cause of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding. If the bleed into the biliary tree is small and chronic, it may present with recurrent melena [

9].

Colour Doppler may show a pulsatile, disorganized arterial flow pattern or characteristic bidirectional flow. If endoscopy reveals bleeding through the papilla of Vater, haemobilia could be more readily diagnosed [

8]. It is possible to miss bleeding from the papilla in patients with haemobilia as it may be intermittent in nature or simultaneous rupture into the duodenum may provide an alternative route for the blood to come out [

7].

Non-contrast CT can show an enhancing mass communicating with the artery which appears as a hyperdense lesion. This enhances in the arterial phase. It helps to confirm the diagnosis in patients with an equivocal Doppler examination before proceeding for an invasive procedure and may localise the blood vessel involved [

7].

A selective hepatic artery angiography is thought to be the gold standard in highlighting the splanchnic vascular system and the pseudoaneurysm can be treated simultaneously via coil embolization [

9]. It has been suggested that in patients with cystic artery pseudoaneurysms, angiography should be done before surgery to help plan the operative procedure.

Most commonly, angiographic embolisation is used especially in haemodynamically stable patients. Transcatheter embolization can be performed using several types of material, such as synthetic occlusive emulsions, gelatin sponges or other particles, or metallic microcoils [

4]. Super-selective catheterization of an artery and release of microcoils causes the vessel to thrombose and allows control of bleeding [

2]. Although embolisation for a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm developing after cholecystectomy is considered to be a de?nitive therapy, in cases of cholecystitis-related pseudoaneurysms, this procedure should only be considered as a temporary treatment before a cholecystectomy.

However, Delgadillo et al. reported a patient with a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery accompanied by cholecystitis that was treated only by embolizing the cystic artery with microcoils, with no recurrence during the following 5 months [

2]. In patients whose general condition would not tolerate surgery, selective embolization alone may be suf?cient to treat a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery [

10].

However, ligation of the cystic artery pseudoaneurysm with cholecystectomy is the final treatment of choice [

7]. The proximal control of the hepatic artery (i.e. encirclement of the proximal hepatic artery in preparation for temporal vascular clamping) may be mandatory in order to avoid serious and uncontrollable bleeding [

5]. Serious bleeding can be precipitated, when dissection is performed in an area where there is evidence of acute inflammation containing a pseudoaneurysm [

7].

The first reported case of the two step treatment of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm was in 2002. After a diagnosis of haemobilia was made, the patient underwent successful embolisation of the cystic artery and ten days later underwent an elective cholecystectomy with a good postoperative course [

10].

In haemodynamically unstable patients with clinical and radiological evidence of cystic artery haemorrhage, operative haemorrhage control is required and this enables concurrent cholecystectomy [

6]. The 3 major modalities used to reveal and study the size, location, and morphology of an aneurysm include thin-section CT scanning after an intravenous injection using special computer software CT angiography [CTA]; MRA and catheter angiography [

11].

Our patient’s CT findings, high CA 19-9 levels and history of unintentional weight loss and malaise prompted the provisional diagnosis of a gallbladder carcinoma triggering a cystic artery pseduoaneurysm formation. However, CA 19-9 levels can be elevated in benign biliary tree diseases such as cholecystitis, hepatitis and cirrhosis. Since the markedly elevated CA 19-9 level was only transient in our patient and he became asymptomatic on review, his presentation could have been due to a benign process, mainly cholecystitis. Furthermore, the repeat CT showed improvement in inflammatory changes. Interestingly, there have not been any documented cases in English literature of gallbladder carcinoma causing cystic artery pseudoaneurysms. However, histopathology from a cholecystectomy will help confirm the diagnosis.

In conclusion, when patients present with gastrointestinal bleeding including melena, jaundice and upper abdominal pain and when gastroscopy reveals no active bleeding, haemobilia should be considered as a possible cause of their symptoms. Although the cystic artery may thrombose in inflammatory states, cholecystitis may trigger a pseudoaneurysm formation if the patient is over anticoagulated. Angiographic coil embolisation is the mainstay treatment unless the patient is haemodynamically unstable. Surgery will be a more suitable option then.

References

- Niknam R, Afrough R, Mahmoudi L. Hemobilia Due to Rupture of Hepatic Artery Pseudoaneursym. Acta Medica Iranica. 2011;49:633-636.

- Delgadillo X, Berney T, de Parrot M, Didier D, Morel P. Successful treatment of a pseudoaneursym of the cystic artery with microcoil embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:789-792.

- Anderson O, Faroug R, Davidson BR, Goode JA. Mirizzi Syndrome associated with hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2008;2:351.

- Desai AU, Saunders MP, Anderson HJ, Howlett DC. Successful Transcatheter Arterial Embolisation of a Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm Secondary to Calculus Cholecystitis: A Case Report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2010;4:18-22.

- Akatsu T, Tanabe M, Shimizu T, Handa K, Kawachi S, Aiura K. Pseudoaneurysm of the Cystic Artery Secondary to Cholecystitis as a Cause of Hemobilia: Report of a Case. Surg Today. 2007;37:412-417.

- Fung AK, Vosough A, Olsen S, Aly EH, Binnie NR. An Unusual cause of acute internal haemorrhage: cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to acute cholecystitis. Scottish medical journal. 2013;58:23-26.

- Saluja SS, Ray A, Gulatti MS, Pal S, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Acute Cholecystitis with massive upper gastrointestinal bleed: A case report and review of the literaturew. BMC Gasteroenterology. 2007; 7:12.

- Nakajima M, Hoshino H, Hayashi E, Nagano K, Nishimura D, Katada N. Case Report: Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:750-754.

- Shah C, Johnson PT, Bhanushali A. Hepatic Artery Pseudoaneurysm. SonoWorld. Available from http://sonoworld.com/CaseDetails/Hepatic_artery_pseudoaneurysm.aspx?ModuleCategoryId=290.html. Accessed on 3rd August 2013.

- Maeda A, Kunou T, Saeki S, Aono k, Murata T, Niinomi N, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with hemobilia treated by arterial embolization and elective cholecystectomy. Journal of Hepato Biliary Pancreatic Surgery. 2002; 9:755-758.

- Joshua SA, Nayak SG, Pare VS, Ashok, Sebastian R. Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Involving the Distal Anterior Cerebral Artery: A Cadaveric Study. Journal of Case Reports. 2013;3:5-9.