Introduction

Uterine rupture, one of the causes of acute abdomen in pregnancy, is an emergent obstetric condition that can lead to maternal and fetal death. Although it is usually seen in the latter part of the pregnancy or during labour, uncommon cases of early pregnancy uterine rupture have also been reported. The highest risk factor for pregnancy uterine rupture is prior caesarean section. Caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) occurring as a result of embryo implantation on the incision scar of the uterus after caesarean birth, is a rare but potentially catastrophic complication of the previous pregnancy [1]. A delay in the diagnosis or treatment may result in uterine rupture, hysterectomy and serious maternal morbidity [2].

We present a case of complete uterine rupture in an 11 week gravida to emphasize the importance of accurate and early diagnosis of an intrauterine normal pregnancy at the early stage examination of pregnancy, particularly among those who had previous caesarean delivery.

Case Report

Twenty nine years of age, gravida:7, para:2 (caesarean delivery due to non-progressive labour in 2000 and caesarean delivery in 2002); abortion:4 (pregnancy losses of 12-14 weeks: two before the first delivery, two after the second delivery; the last curettage was done 3 years before). The patient had pregnancy control 3 times before and the pregnancy week was found to be consistent with the date of her last menstrual period. The patient consulted to the hospital where she had her pregnancy controls with the complaint of fainting three times, and she was referred to a higher hospital. Her physical examination performed at this centre revealed no vaginal bleeding and a closed cervix. In the ultrasound evaluation, crown-rump length was 47 mm (11+3), foetal cardiac activity was (+), placenta was posteriorly located, amnion fluid was adequate, and no retrochorionic hematoma was observed. The patient’s blood values were pH: 6.820; pCO2: 49 mmHg; pO2: 20.6 mmHg; haematocrit: 20.8%; haemoglobin: 6.6 g/dL; SpO2: 12%; potassium: 2.9 mmol/L; sodium: 126 mmol/L; calcium: 1.10 mmol/L; glucose: 616 mg/dL; and lactate: 16 mmol/L. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hyperglycaemia and lactic acidosis. Glucose levels continued to be high and a sudden abdominal pain developed approximately 18 hours later. In the ultrasound, diffuse free fluid was detected in the abdomen. Her haematocrit was 16 g/dL, and the patient was referred to our hospital in shock.

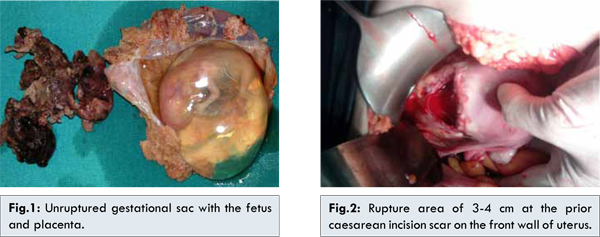

The patient was admitted to general surgery department with the preliminary diagnosis of acute abdomen and intra-abdominal bleeding, and an emergency laparotomy was performed. Approximately 2000 cc blood and coagulum was found in the abdominal cavity, accompanied with a complete rupture on the anterior wall of the uterus and an unruptured gestational sac containing a fetus inside [Fig.1]. Gynaecologic consultation was asked for the patient due to uterine rupture, and a rupture area of 3-4 cm was detected on a prior caesarean incision scar on the front wall of uterus [Fig.2].

After cleaning of the uterine cavity, the uterus was observed not to be contractible. Additionally, there was a bleeding area at the ruptured area close to the bladder. Intravenous oxytocin infusion, local oxytocin injection into the uterus and bilateral uterine artery ligation were applied. Subtotal hysterectomy was performed because of continuing bleeding, un-contractible uterus and failure to stabilize the patient’s haemodynamics. Five units of erythrocyte suspension and 5 units of fresh frozen plasma were administered per-operatively to the patient. The patient was taken to the ward after two days in intensive care unit. On the 12th day after operation, the patient was discharged without any complication. No relevant problems developed in the patient during the 2-year follow-up period.

A pre-viable fetus consistent with 11-12 pregnancy weeks, presence of invasive chorionic villi among the myometrial muscle fibres in the uterus (placenta accreta) and adenomyosis focuses were found upon pathological evaluation [Fig.3].

Discussion

Uterine rupture, one of the causes of acute abdomen seen at pregnancy, is a rare condition; however carries a high maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity. The most frequent cause of uterine rupture in pregnancy is the uterine scar dehiscence. It may also be associated with grand multiparity, cephalopelvic disproportion or transvers position, and excess stimulation with oxytocin. The condition is seen in 0.07- 0.1% of all term pregnancies [3].

In CSP occurring as a result of embryo implantation into the caesarean scar in the uterus seen in those who had caesarean delivery, the gestational sac is completely surrounded by myometrium and fibrous tissue of the scar. The cause and mechanisms are not fully elucidated. The most probable mechanism may be expressed as the myometrial invasion of the conception product through a microtubular pathway between the caesarean scar in the uterus and endometrial canal. Such a pathway can be formed following curettage, myomectomy, metroplastia, hysteroscopy, and even after manual removal of the placenta [1]. The rate of pregnancy development on the prior hysterotomy (caesarean) scar is about 1/2000 and about 6% of ectopic pregnancies among women with prior caesarean delivery is CSP [4]. We did not encounter any data regarding the frequency of spontaneous uterine rupture in the first trimester CSP in the literature, probably due to the extreme rarity of the disorder.

Primary discretional caesarean deliveries are increasing at the present time. The incidence of CSP, the rarest type of ectopic pregnancy, will probably increase with the increasing caesarean deliveries. Being suspicious is essential, especially in patients who have risk factors. While evaluating the location of gestational sac, it may be difficult to distinguish spontaneous abortion course, cervico-isthmic pregnancy and CSP in cases where the sac is located at the bottom of the uterine cavity. Transvaginal ultrasonography combined with Doppler is a proper instrument for diagnosis. The diagnostic criteria here are as follows: an empty endometrial cavity and cervical canal, a gestational sac developed on the front isthmus wall of the uterus (with or without fetal cardiac activity according to the gestational age, with or without fetus inside) absent or defective myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder, and presence of functional trophoblastic circulation in Doppler examination [1,5].

Accurate diagnosis at an early stage is of utmost importance in the management of caesarean scar gestation cases. In cases detected at an early stage, protection of uterus can be ensured through a successful medical treatment or a medical treatment combined with surgery. Such treatment modalities include administration of systemic or local methotrexate, insertion of a Foley catheter after dilatation and curettage, embolization of the uterus artery, and hysterotomy. However, in situations where adequate diagnosis and treatment are not established at the early stage, especially in cases with a viable fetus inside, gestational sac grows and may lead to uterine rupture resulting in extremely hazardous maternal and fetal outcomes which can be life endangering.

First trimester spontaneous uterine rupture associated with CSP has no standard treatment procedure, since these cases are presented in the literature as case reports [6]. In a series of 15 cases receiving medical treatment with a diagnosis of caesarean scar gestation, total hysterectomy was performed in 2 patients due to massive vaginal bleeding [7]. In another series of 18 cases administered medical and/or surgical treatment, 1 patient underwent emergency hysterectomy after serious bleeding [8]. In our case, pregnancy was first detected at week 8, and she had been examined 4 times at different time points until consulting to our clinic. She had two risk factors for a caesarean scar gestation (two caesarean deliveries and four curettages). Unfortunately, an early and accurate diagnosis could not be established, and she was followed up as a normal pregnancy. Our case had developed a CSP, and uterine rupture occurred at week 11 of pregnancy because of the delay in diagnosis, and the situation became catastrophic upon excess intra-abdominal bleeding. The patient’s vital signs could only return to normal after subtotal hysterectomy and extensive replacement. Placenta accreta outside the ruptured area was detected upon the pathological evaluation of uterus. The bleeding outside the ruptured area might be associated with placenta accreta.

In a case presentation by Matsuo et al. [9], gestational sac was found to be localized on the lower segment of front uterine wall and a defect was seen on the prior caesarean scar at the ultrasound examination of a gravida with Type 1 diabetes mellitus presenting with abnormal genital bleeding and abdominal pain. The patient underwent an emergency laparotomy one day later with the diagnosis of spontaneous uterine rupture, and uterus repair was performed. As for our case, the presence of prior diabetes was not known. Blood glucose levels remained high during the intensive care stay one day before the uterine rupture; however, these levels were within the normal range during the post-operative follow-up.

At the examination of patients presenting in the early pregnancy, lower segment of the uterus should also be evaluated; and abnormal pregnancies such as caesarean scar gestation, cervical pregnancy and placentation abnormalities should also be sought, especially in those with prior caesarean delivery.

Conclusion

In CSP cases in which an early and accurate diagnosis could not be established or was neglected, uterine rupture, acute abdomen and relevant life endangering outcomes even in the first trimester pregnancy are the undesirable events that may finally occur. During the ultrasound examination of patients presenting with suspected pregnancy, location of gestational sac can be overlooked while evaluating the gestational sac, fetus and fetal cardiac activity.

References

- Ash A, Smith A, Maxwell D. Caesarean scar pregnancy. BJOG. 2007;114:253-263.

- Fylstra DL. Ectopic pregnancy within a cesarean scar: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57(8):537-543.

- Martínez-Garza PA, Robles-Landa LP, Roca-Cabrera M, Visag-Castillo VJ, Reyes-Espejel L, García-Vivanco D. Spontaneous uterine rupture: report of two cases. Cir Cir. 2012;80(1):81-85.

- Marion LL, Meeks GR. Ectopic Pregnancy: History, Incidence, Epidemiology, and Risk Factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(2):376-386.

- Tan G, Chong YS, Biswas A. Caesarean scar pregnancy: a diagnosis to consider carefully in patients with risk factors. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34(2):216-219.

- Litwicka K, Greco E. Caesarean scar pregnancy: A review of management options. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23(6):415-421.

- Weimin W, Wenqing L. Effect of early pregnancy on a previous lower segment cesarean section scar. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77(3):201-207.

- Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(3):220-227.

- Matsuo K, Shimoya K, Shinkai T, Ohashi H, Koyama M, Yamasaki M, Murata Y. Uterine rupture of cesarean scar related to spontaneous abortion in the first trimester. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(1):34-36.