|

|

|

|

|

Unusual Presentation of Sturge Weber Syndrome

|

|

|

naloxone versus naltrexone opioid when to use naloxone vs naltrexone knagis.miga.lv

Department of Radiodiagnosis and Imaging, Government Medical College, Amritsar 143001, Punjab, India. |

|

|

|

|

|

Corresponding Author:

|

Dr. Garima Gupta

Email: ggupta085@gmail.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received:

20-DEC-2014 |

Accepted:

21-FEB-2015 |

Published Online:

15-MAR-2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

|

|

|

|

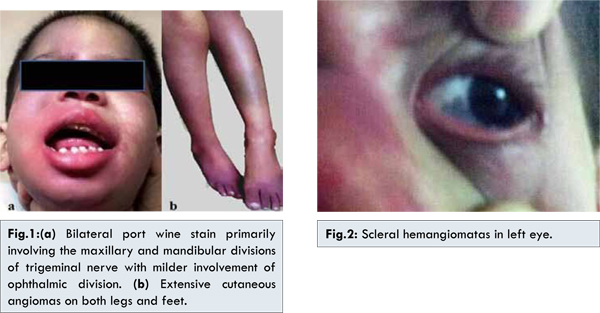

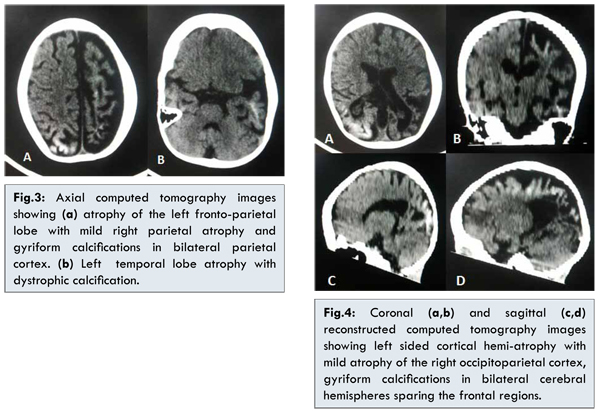

Sturge-Weber syndrome is characterized by unilateral facial port wine stain, ipsilateral leptomeningeal vascular anomalies, ipsilateral choroidal angiomas which lead to glaucoma and one or more symptoms (epilepsy, hemiparesis, hemiplegia or mental retardation). We hereby, present a case of 5 year old girl with seizure disorder, right sided hemiparesis along with angiomas on both sides of her face, more extensive and prominent on her upper and lower limbs. Ocular examination revealed raised intraocular pressure and choroidal hemangiomas in both eyes. Non contrast enhanced computerized tomography of head showed left sided cortical hemi-atrophy with mild atrophy of the right occipito-parietal cortex. Gyriform calcifications were seen in bilateral temporo-occipitoparietal regions. The case was diagnosed as bilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome with extensive extrafacial distribution of cutaneous lesions. |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

Sturge-Weber syndrome, Port-Wine stain, Epilepsy, Paresis, Atrophy, Intraocular Pressure, Humans.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff9417060000009403000001000100 6go6ckt5b5idvals|438 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), also known as ’encephalotrigeminal angiomyomatosis’ is a neuro-cutaneous disorder of unknown etiology characterized by the presence of nevus flammeus (port wine stain) affecting the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve and ipsilateral cerebral pial angiomyomatosis with ipsilateral choroidal angiomas [1]. Bilateral skin lesions and cortical involvement are rarely described. Hence, we present an unusual case of bilateral Sturge Weber syndrome along with extrafacial cutaneous involvement and bilateral glaucoma.

Case Report

A 5 year old girl presented with status epilepticus, right sided hemiparesis and diminished vision in both eyes. Past medical history revealed that blanchable cutaneous angiomas were present on face and extremities since birth. 21 days after birth, the child had clonic seizure of the right arm with secondary generalization, without any fever. Seizures were refractory to aggressive anticonvulsant therapy. She developed progressive visual loss and mild to moderate developmental delay along with right sided hemiparesis since the age of 6 months. Child also developed autistic behavioral features in the form of rocking and head banging. Previous brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) done at the age of six months revealed gliotic changes and atrophy of left temporo-occipitoparietal lobe with mild gliotic changes in the right peritrigonal region.

On recent hospital admission, physical examination showed cutaneous angiomas on face, predominantly on the right side primarily involving the distribution of maxillary and mandibular divisions of trigeminal nerve with milder involvement of ophthalmic division [Fig.1]. Few similar lesions were seen on the neck and upper back. More extensive angiomas were observed on her both upper and lower limbs [Fig.1] with sparing of palms and soles. Ophthalmological assessment revealed raised intraocular pressure and choroidal and scleral hemangiomata in both the eyes [Fig.2]. Non contrast enhanced computerized tomography (NCCT) of head revealed left sided cortical hemi-atrophy with mild atrophy of the right occipitoparietal cortex [Fig.3,4]. Gyriform calcifications were seen in bilateral cerebral hemispheres sparing the frontal regions [Fig.3,4]. Intracranial calcifications were not seen on lateral X–ray skull. MRI brain was advised but could not be done because of financial constraints. In view of the clinical features, examination and imaging findings, a provisional diagnosis of Sturge-Weber syndrome was made.

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a rare, sporadic congenital disorder characterized by a triad of cutaneous, cranial and ocular involvement, in the form of facial port wine stain (PWS), pial angiomas and glaucoma respectively. These abnormalities are attributed to malformation of an embryonic vascular plexus within the cephalic mesenchyme between the neuroectoderm and the telencephalic vesicle. The severity and extent of presentation is determined by the developmental time point at which the mutations occurred in the GNAQ gene in the vascular endothelial cells [2].

Earliest descriptions of SWS had been made by Sturge, and Weber demonstrated the characteristic intracranial gyriform calcifications [3,4]. Sturge-Weber syndrome is quite heterogeneous in its manifestations with wide variability in the natural history. Roach proposed a classification system to address this broad spectrum of Sturge-Weber syndrome presentations. Type I presents with both facial and leptomeningeal angiomas. Type II has a facial angioma without central nervous system leptomeningeal angiomatosis. Isolated leptomeningeal angiomatosis without a facial port-wine nevus is classified as Type III [5].

PWS is evident at birth usually affecting the upper face ipsilateral to the leptomeningeal angiomatosis. Bilateral skin lesions have been seen in 20% cases [6]. Extension of hemangioma to neck, trunk and extremities is seen in 34% of the patients of bilateral facial hemangiomas while 9% of patients with a unilateral facial hemangioma have an extra-facial hemangioma [7]. The present case had bilateral facial and extrafacial nevus flammeus and the latter were much more prominent and extensive.

Leptomeningeal angiomatosis, usually unilateral is the characteristic neuroimaging finding associated with SWS, involving the occipital and posterior parietal lobes. Bilateral intracranial involvement has been reported in 15% and does not correlate with the unilateral or bilateral appearance of the facial birthmark [8]. The angiomatosis is associated with poor superficial cortical venous drainage promoting chronic hypoxia of both the cortex and the underlying white matter. This ultimately leads to laminar cortical necrosis, neuronal loss, gliosis and dystrophic calcification [9]. Early cerebral atrophy may be associated with homolateral hypertrophy of the skull and sinuses, the Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome [10]. Cerebral hypoxia and stasis further leads to seizures that are observed in a majority of children with SWS. The seizures are primarily partial motor that often become secondarily generalized tonic-clonic. Bilateral intracranial involvement is associated with earlier onset of refractory seizures, developmental delays and poor cognitive development as in our case [11,12]. Hemiparesis (contralateral to the facial and intracranial lesions), migraine and recurrent stroke like episodes may also occur.

The ocular manifestations include ipsilateral choroidal and scleral telangiectasia. The choroidal angioma may alter the physiology of intraocular pressure leading to glaucoma. Glaucoma is the most common ophthalmic complication of SWS, occurring in 30-70% of patients. In 60% cases glaucoma develops in infancy when the eye is susceptible to increased intraocular pressure. Majority of patients with unilateral facial PWS have ipsilateral glaucoma. With bilateral facial PWS, 45% have bilateral glaucoma, as seen in the present case. Children with nevus on the eyelids are at elevated risk for eye and brain disease [13].

Advances in neuroimaging techniques have afforded a more precise look at the pathology of SWS. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography are the imaging modalities most widely used. Plain X ray skull and angiography are less useful. Plain skull radiographs reveal intracranial calcifications that are often gyriform and curvilinear, located in the cortex underlying the leptomeningeal vascular malformations, and are usually not seen before the patient reaches 2 years of age [14].

CT scan in SWS shows the enhancing angiomatous malformation and secondary brain changes which include ipsilateral cortical atrophy, gyriform calcification, enlargement of the ipsilateral lateral ventricle and its choroid plexus. In severe cases, a Dyke-Davidoff-Masson appearance may be seen. CT is more sensitive than radiography and MRI in detection of subcortical calcifications in patients younger than 2 years [10,15]. MRI reveals intense pial enhancement due to angiomatous malformation and subjacent cerebral atrophy. Choroidal lesions are well depicted on contrast-enhanced orbital MRIs. In addition, MRI helps to evaluate the extent of involvement and correlates better than CT with clinical progression [16].

There is no cure for this syndrome. The treatment in SWS revolves primarily around seizure control, with surgical resection only indicated in refractory cases. Physical therapy should be considered for children with muscle weakness and educational therapy for those with mental retardation or developmental delays. Glaucoma requires combined management using medical and surgical approaches, while management of port-wine stains involves laser therapy.

Conclusion

The present case report highlights unusual presentation of SWS in the form of bilateral cortical, cutaneous and ocular involvement along with widespread extrafacial cutaneous involvement.

References

- Aicardi J. Diseases of the Nervous System in Childhood. Cambridge and New York: Mac Keith Press and Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, Carol J, Baugher JD, Frelin LP, et al. Sturge-Weber Syndrome and Port-Wine Stains Caused by Somatic Mutation in GNAQ. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Sturge WA. A case of partial epilepsy apparently due to a lesion of one of the vasomotor centres of the brain. Trans Clin Soc Lond. 1879;12:162-167.

- Weber FP. Right-sided hemi-hypertrophy resulting from right-sided congenital spastic hemiplegia, with a morbid condition of the left side of the brain, revealed by radiograms. J Neurol Psychopathol. 1922;3:134-139.

- Roach ES. Neurocutaneous syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1992;39:591-620.

- Mittal K, Kaushik JS, Kaur G, Aamir M, Sharma S. Unusual presentation of Sturge-Weber syndrome: Progressive megalencephaly with bilateral cutaneous and cortical involvement. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2014;17(2):207-208.

- Uram M, Zubillaga C. The cutaneous manifestation of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Clin Neuro Ophthalmol. 1982;2:245-248.

- Pascual-Castroviejo I, Diaz-Gonzalez C, Garcia-Melian RM, Gonzalez-Casado I, Munoz-Hiraldo E. Sturge-Weber syndrome: study of 40 patients. Pediatr Neurol. 1993;9:283-288.

- Thomas-Sohl KA, Vaslow DF, Maria BL. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:303-310.

- Dyke DG, Davidoff LM, Masson CB. Cerebral hemiatrophy with homolateral hypertrophy of the skull and sinuses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1933;57:588-600.

- Alkonyi B, Chugani HT, Karia S, Behen ME, Juhász C. Clinical outcome in bilateral Sturge Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:443-449.

- Bebin EM, Gomez MR. Prognosis in Sturge-Weber disease: comparison of unihemispheric and bihemispheric involvement. J Child Neurol. 1988;3:181-184.

- Roach ES. Congenital cutaneovascular disorders. In: Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, eds. Stroke syndromes. London: Cambridge University Press, 1995:481-490.

- Boyer RS. Disorders of histogenesis: neurocutaneous syndromes. In: Osborn AG, eds. Diagnostic neuroradiology. St Louis, Mo: Mosby,1994;72-113.

- Tasdemir HA, Incesu L, Yazicioglu AK. Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome. Clin Imaging. 2002;26(1):13-17.

- Griffiths PD. Sturge-Weber syndrome revisited: the role of neuroradiology. Neuropediatrics. 1996;27:284-294.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Google Scholar for

|

|

|

Article Statistics |

|

Bhagat S, Gupta G, Singh SUnusual Presentation of Sturge Weber Syndrome.JCR 2015;5:111-115 |

|

Bhagat S, Gupta G, Singh SUnusual Presentation of Sturge Weber Syndrome.JCR [serial online] 2015[cited 2025 Oct 23];5:111-115. Available from: http://www.casereports.in/articles/5/1/Unusual-Presentation-of-Sturge-Weber-Syndrome.html |

|

|

|

|

|