6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff642e170000007503000001000b00

6go6ckt5b5idvals|735

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Hypersensitivity reaction towards the germinating fungal spores in the airways results in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA). It is seen in patients with asthma (1-2%) and cystic fibrosis (5-10%), thereby complicating its course. These patients usually present with exacerbation of asthma, fever and cough with expectoration [

1]. However, acute onset dyspnea following lung collapse due to mucus plug obstruction as a result of ABPA has rarely been reported.

Case Report

A 75 year old lady presented with history of dyspnea since 5 days, which became severe since the morning of presentation. There were no other associated or systemic symptoms. She is an asthmatic for the past 20 years on inhalers (formoterol and budesonide) and montelukast (10 mg) tablet. There is no history of similar episode in the past. She is also a hypertensive (on telmisartan 40 mg once daily).

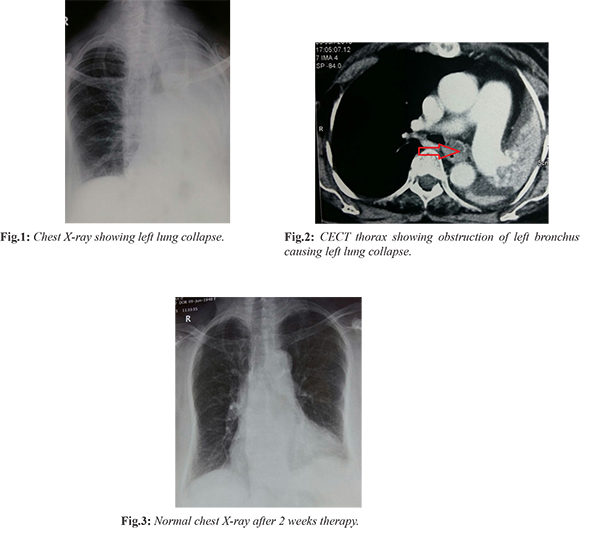

On examination, she was conscious, oriented and afebrile. She was tachypneic (24 breaths/ minute) with saturation 90% in room air. Her heart rate was 100 beats/ minute and blood pressure 140/90 mmHg. Respiratory system examination revealed a left mediastinal shift; with decreased chest movements, dull percussion note and decreased breath sounds on the left side. Other systemic examinations were normal. Her complete blood count showed eosinophilia (E 20%). Other blood investigations like renal and liver functions and electrolytes were normal. ECG showed left ventricular hypertrophy with sinus tachycardia. Left lung collapse was visible on chest X-ray [Fig.1]. Contrast enhanced CT thorax showed left lung collapse with herniation of the opposite lung and a non-enhancing lesion (probably a mass or mucus plus) completely obstructing the left main bronchus [Fig.2]. Bronchoscopy showed a thick mucus plug in the left upper and lower bronchi, which was cleared off with Mesna instillation. Bronchoalveolar lavage specimen showed fungal hyphae of Asperigillus fumigatus; while AFB stain, cultures and cytology were negative. Serum IgE levels were elevated (3700 IU/mL) along with serum A. fumigatus specific IgG levels (42.81 U/mL). Her absolute eosinophil count was also elevated (2400 cells/µL) and skin test to A. fumigatus extract was positive. In view of the history of asthma and the investigation results, the diagnosis of ABPA was made. She was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily, which was continued for 4 months. Oral prednisolone was also administered at 0.75 mg/kg/day for 2 months, followed by 0.5 mg/kg/day for 2 months and then tapered as 10 mg/day for 2 weeks, 5 mg/day for 2 weeks and stopped. Her repeat chest X-ray after 1 week of therapy was normal [Fig.3]. Serum IgE level repeated after 2 months was normal. She remained asymptomatic throughout the course of her treatment and continues to be on inhalers (formoterol and budesonide) with regular follow ups.

Discussion

ABPA results from an allergic immune response to Aspergillus fumigatus. It is commonly seen in patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis. The activation of host T lymphocytes in response to aspergillus leads to the recruitment of eosinophils and other inflammatory mediators.

The relationship between asthma and ABPA is unclear. About 25% of asthmatics get sensitized to aspergillus, but only a fraction of them develop ABPA [

2]. Airway abnormalities and excessive mucus production may act as contributory factors. The incidence of ABPA typically occurs many years after the diagnosis of asthma; and is more common among adults [

3]. With the development of ABPA, these asthmatic patients face a worsening of symptoms like cough, mucus production and wheezing. The mucus is thick and resistant to suctioning [

4]. These patients may cough out brownish-black mucus plugs composed of degenerating eosinophils, desquamated epithelial cells, and mucin [

5]. Hemoptysis may be seen in the presence of an underlying bronchiectasis. Other symptoms include low grade fever and weight loss [

1]. Several diagnostic criteria have been proposed for the diagnosis of ABPA. Our patient satisfied 5 out of the 8 criteria stated by Rosenberg et al., thereby confirming the diagnosis of ABPA [

6]. A revised diagnostic criteria was outlined by Greenberg et al. in 1991 [

7]. Our patient did not have any positive culture report for broncho-alveolar specimen. The sensitivity or specificity of aspergillus culture from broncho-alveolar lavage or sputum samples is poor; and its presence does not indicate active disease [

8].

The incidence of lung collapse following mucus plugging with aspergillosis is a rare scenario. Nomura et al. presented the case of a young individual with respiratory disease in whom the diagnosis of ABPA was confirmed with bronchoscopy [

9]. Berkin et al. reported two cases of lung collapse due to ABPA in non-asthmatic patients [

10]. In a case mentioned by Agarwal et al. the patient presented in respiratory failure following lung collapse due to ABPA [

11]. In another case by Ghosh et al. the cause for lung collapse following mucus plug obstruction by ABPA was misdiagnosed as carcinoma lung [

12].

The aim of therapy is to induce remission, which is characterized by symptomatic relief, decrease in levels of total serum IgE, improvement in lung functions and resolution of radiographic opacities. Systemic corticosteroids form the mainstay of therapy by reducing the inflammatory response to aspergillus in the lung. An aggressive regimen suggests prednisolone 0.75 mg/kg daily for 6 weeks, then 0.5 mg/kg daily for 6 weeks, then tapered by 5 mg daily every 6 weeks, for a total of 6 to 12 months. Serum total IgE have to be repeated every 8 to 12 weeks for 1 year, then annually [

13]. Antifungal agents reduce the burden of fungal organisms and prevent antigenic stimulation. It also facilitates the reduction in the dosage of oral steroids. Itraconazole is the drug of choice [

1,

14]. Monoclonal antibody against IgE like omalizumab may be of benefit [

15].

Conclusion

ABPA is a form of complex hypersensitivity reaction in response to A. fumigatus; commonly seen in association with cystic fibrosis and bronchial asthma. These patients usually present with exacerbation of symptoms. However, only a handful of cases have been reported with regard to ABPA presenting as lung collapse. This case highlights the need to consider ABPA as a differential diagnosis for atelectasis, especially in those patients with underlying respiratory conditions like asthma.

Contributors: MCS: Concept and design of case report and treating pulmonologist; RGM: Literature review, manuscript preparation and treating physician; AKD, PK: Critical revision of manuscript and treating pulmonologists; NV: Literature review and treating pulmonologist. RGM will act as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Reid PT, Innes JA. Respiratory disease. In: Walker BR, Colledge NR, Ralston SH, Penman ID (eds). Davindon’s Principles & Practice of Medicine. 22nd ed. Elsevier Limited. pp. 697-698.

- Novey HS. Epidemiology of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 1998;18:641-653.

- Ricketti AJ, Greenberger PA, Mintzer RA, Patterson R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 1984; 86:773-778.

- Greenberger PA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;110:685-692.

- Kradin RL, Mark EJ. The pathology of pulmonary disorders due to aspergillus spp. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:606-614.

- Rosenberg M, Patterson R, Mintzer R, Cooper BJ, Roberts M, Harris KE. Clinical and immunologic criteria for the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:405-414.

- Schwartz HJ, Greenberger PA. The prevalence of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with asthma, determined by serologic and radiologic criteria in patients at risk. J Lab Clin Med. 1991;117:138-142.

- Riscili BP, Wood KL. Noninvasive pulmonary aspergillus infections. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30:315-335.

- Nomura K, Sim JJ, Yamashiro Y, Hoshino M, Nakayama H, Hosaka K, et al. Total collapse of the right lung in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;36:469-472.

- Berkin KE, Vernon DR, Kerr JW. Lung collapse caused by allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in non-asthmatic patients. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285:552-553.

- Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Gupta N, Gupta D. A rare cause of acute respiratory failure-allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2011;54:e223-227.

- Ghosh K, Sanders BE. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis causing total lung collapse. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5349.

- Vlahakis NE, Aksamit TR. Diagnosis and treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:930-938.

- Wark PAB, Hensley MJ, Saltos N, Boyle MJ, Toneguzzi RC, Simpson JL, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of itraconazole in stable allergic bronchopumonary aspergillosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:952-957.

- van der Ent CK, Hoekstra H, Rijkers GT. Successful treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with recombinant anti-IgE antibody. Thorax. 2007; 62:276-277.