|

|

|

|

|

Neutropenia in Sirolimus Treated Patients of Lymphatic Malformation: A Case Series

|

|

|

|

Lama Altawil1, Nada Fouda Neel2, Alanoud Alhedyani1, Mohammad Badran3, Riyadh Alokaili3, Saad AlAjlan4 Student, College of Medicine, 1King Saud University and 2Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Departments of 3Radiology and 4Dermatology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. |

|

|

|

|

|

Corresponding Author:

|

|

Dr. Saad Alajlan Email: salajlan@kfshrc.edu.sa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received:

20-JAN-2017 |

Accepted:

04-APR-2017 |

Published Online:

05-MAY-2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

|

|

|

|

Background: Lymphatic malformations (LMs) are rare benign tumors that are at risk of various complications due to their progressive nature and critical locations. Considering the morbidity and mortality of such lesions, different therapeutic methods proposed are surgical excision, sclerotherapy, laser, aspiration, radiotherapy, and most recently sirolimus. Case Reports: We reviewed 3 cases with lymphatic malformation at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Initially placed on various treatment sessions of surgical intervention, sclerotherapy or even both prior to sirolimus, minimal improvement was noted. Sirolimus initiation was associated with significant clinical improvement. However, sirolimus was associated with neutropenia, which was successfully managed by G-CSF. Conclusion: Sirolimus can cause bone marrow suppression due to cumulative effect. |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

Bone Marrow, Lymphatic Abnormalities, Neoplasms, Neutropenia, Sirolimus.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff64a5180000000d06000001000100 6go6ckt5b5idvals|751 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Lymphatic malformations (LM) account for significant morbidity and mortality, as they continue to grow and cause the adverse effects of any space-occupying lesion [ 1, 2]. Different therapeutic methods like surgical excision: the first line of treatment; and the non-surgical methods which include sclerotherapy, laser, aspiration, and radiotherapy have been proposed [ 3]. These classical methods of treatment have their limitations, hence the popularity of incorporating sirolimus in the therapeutic regimen of complex cases had risen. Consequently, the side effects which have been noted in different populations such as bone marrow suppression in kidney transplant patients is now becoming more evident in LM populations treated with the sirolimus [ 3]. In this case series, we corroborate with what has been reported on sirolimus as an effective therapeutic regimen in the treatment of lymphatic malformation. Also, we will highlight the possible bone marrow suppression as unique adverse effect in three cases reviewed in the Dermatology department at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (KFSHRC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Case Reports

Case 1

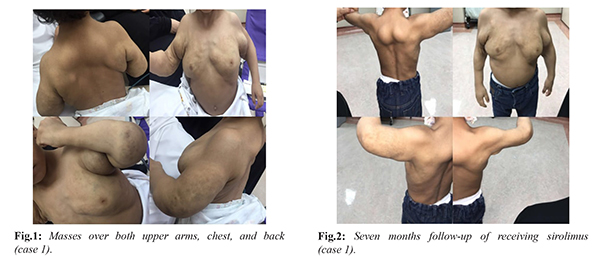

A 2 years old male, was referred to the dermatology clinic at KFSHRC for masses over both upper arms and chest and back [Fig.1]. A diagnosis of macrocytic lymphatic malformation over the upper trunk and bilateral axillary was established. The patient underwent multiple sessions of sclerotherapy with minimal improvement noted. Sirolimus was introduced as an adjuvant therapy with a dose of 0.8 mg/m2/day after family education and singed consent was provided. The dose was increased in small increments to 1.25 mg/m2/day and thereafter to 1.5 mg/m2/day. Subsequent dose increments were done to reach a trough level of 10-13 µg/L. In two months the dose had reached 1.8 mg/m2/day. However, the patient developed fever and cough along with evident neutropenia (neutrophils absolute 0.33×109/L). Sirolimus level at that time was 2.4 µg/L. Sirolimus was discontinued and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was prescribed for 10 days along with graunulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) 75 µg/week for four weeks. with noted improvement. Sirolimus was resumed at a minimum dose of 1.2 mg/m2/day and same dose of G-CSF was resumed for an additional month. The patient had no recurrence of neutropenia since then and is maintained on sirolimus [Fig.2].

Case 2

A 20 months old female, was referred to the dermatology clinic at KFSHRC with a progressively growing left neck mass [Fig.3]. A diagnosis of left sided anterior triangle cystic hygroma was made. Surgical excision with deep neurovascular dissection was done. The patient underwent multiple sessions of sclerotherapy with minimal improvement noted. Sirolimus was introduced as an adjuvant therapy at a dose of 1.6 mg/m2/day after family education and signed consent was provided. Improvement was noted [Fig.4]. However 22 days later, the patient developed neutropenia (neutrophils absolute 1.07×109/L) without any signs of fever or infection. Sirolimus level at that time was 8.5 µg/L. Sirolimus was continued at the same dose and was given 3 doses of G-CSF 150 µg/L for four weeks. Subsequent increased increments of sirolimus are expected to be added to reach a trough level of 10-13 µg/L.

Case 3

A 12 years old male from Bahrain, was referred to the dermatology clinic at KFSHRC with lymphatic malformation of the right parotid and neck involving facial bones [Fig.5]. Initially he needed tracheotomy and underwent surgery and multiple sessions of sclerotherapy. The patient was well until an eye swelling in the same site of previous surgery appeared. Enhanced facial MRI showed large right facial and submandibular as well as upper neck and posterior triangle lesion. Following the MRI, he was treated by sclerotherapy. The patient lacked response to conventional therapy, sirolimus was started as an add-on treatment after family education and singed consent was provided. Initial dosing was 0.8 mg/m2/day, dosing adjustments were made every 2 weeks in order to optimize the drug trough level to 10-13 µg/L. While on sirolimus the patient had two additional unsuccessful sclerotherapy sessions. After 5 months of sirolimus (1.9 mg/m2/day) the patient developed neutropenia (neutrophils absolute 1.26×109/L). Sirolimus level at that time was 9.0 µg/L. Sirolimus was continued at 1.9 mg/m2/day and G-CSF 128 µg/week for 4 weeks. At present, he remains on sirolimus and there has been no further growth of the mass.

Discussion

LM’s tend to grow in parallel with the patient even if not evident at birth [ 4]. It accounts for 5% of all benign tumors in children and adults [ 5]. Morphologically LMs are divided into macrocystic, microcystic or combined disease [6]. The microcytic variants are generally more challenging to deal with due to their infiltrative nature to vital organs and poor response to therapeutic regimens. To overcome this challenge combining radiofrequency ablation in combination with sclerotherapy as was reported by Niti et al. has led to a 90% improvement and minimal adverse effects [ 7]. Another report by Mitsukawa et al. showed that combining liposuction to disrupt the cyst wall followed by OK-432 on patients in 5 patients led to near complete resolution results [ 8]. Regardless, several treatment options have been proposed yet the literature isn’t enough to design an algorithm that suites all types and locations of lymphatic malformations [ 9]. Several entities such as hyoid level, bilaterally, age of onset, growth rate, type, depth, extent, anatomical location, potential deformity or dysfunction of LMs should be put into consideration before constructing a therapeutic plan [ 9].

Treatment options vary to include the surgical and non-surgical approaches [ 10]. Surgical treatment is considered the first choice and the most common approach in approaching these lesions [ 1]. However, these lesions tend to occur around vital structures such as nerves, or vessels putting them into compromise of being damaged. Some may also be deeply infiltrated making complete resection difficult. For this reason, recurrence rates tend to range between 50-100% [ 11]. Percutaneous sclerotherapy using doxycycline was first reported by Molitch in 1995 [ 12]. Commonly used variants include bleomycin and OK432 [ 13]. They work better with macrocystic variants with the former showing potential in treating microcytic varieties also [ 10]. These two methods of treatment were both attempted in treating our patients as a primary approach whether individually or combined. Other treatment modalities including aspiration usually result in temporary management. Laser excision, radio-frequency ablation, radiation, and cauterization have been employed with variable results [ 9]. Most recently sirolimus was introduced to the market. It acts as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors [ 14].

Before its potential use in treating lymphatic malformation sirolimus was used in kidney transplant patients to prevent allograft rejection. It effectively blocks interleukin-2 stimulation of lymphocyte division. Mutations along the mTOR pathway can lead to the formation of several diseases including vascular malformation [ 15]. Adverse effects in the literature are dose related and include mucositis, hypercholesterolemia, and elevated liver enzymes [ 14]. In all three cases reported by us, the patients were placed on various treatment sessions of surgical intervention, sclerotherapy or both, before initiating sirolimus. Improvement in using sclerotherapy and surgery was minimal if any. After initiating the sirolimus, the patients have shown great improvement as opposed to the baseline level at the time of presentation. Interestingly, the three cases had shown possible bone marrow suppression. They all had neutropenia two months, 22 days, and five months respectively from the time they started sirolimus. All three were managed with G-CSF with weekly dose of 75 µg and 150 µg and 128 µg respectively. One case series reported neutropenia in one of its six patients however the author wasn’t able to attribute it purely on sirolimus [ 14]. We attribute this adverse effect due to the cumulative dose of the drug. However, this adverse effect doesn’t repudiate the use of sirolimus as a treatment option in LM.

Conclusion

Sirolimus is a therapeutic option in the treatment of resistant lymphatic malformation, though it may cause bone marrow suppression. Being a retrospective study, it will need prospective follow up to strengthen it and possibly overcome the selection bias.

Contributors: LA, NFN, AA: manuscript writing, literature search; MB, RA: critical inputs into the manuscript and photographs; SAA: manuscript editing, literature search and case management. SAA will act as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References - Oosthuizen JC, Burns P, Russell JD. Lymphatic malformations: a proposed management algorithm. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:398-403.

- Ghritlaharey RK. Management of Giant Cystic Lymphangioma in an Infant. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1755-1756.

- Huber S, Bruns CJ, Schmid G, Hermann PC, Conrad C, Niess H, et al. Inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin impedes lymphangiogenesis. Kidney Int. 2007;71:771-777.

- Blei F. Medical and genetic aspects of vascular anomalies. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:2-11.

- Chen YL, Lee CC, Yeh ML, Lee JS, Sung TC. Generalized lymphangiomatosis presenting as cardiomegaly. J Formos Med Assoc Taiwan Yi Zhi. 2007;106(3 Suppl):S10-14.

- Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:412-422.

- Niti K, Manish P. Microcystic lymphatic malformation (lymphangioma circumscriptum) treated using a minimally invasive technique of radiofrequency ablation and sclerotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1711-1717.

- Mitsukawa N, Satoh K. New treatment for cystic lymphangiomas of the face and neck: cyst wall rupture and cyst aspiration combined with sclerotherapy. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:1117-1119.

- Zhou Q, Zheng JW, Mai HM, Luo QF, Fan XD, Su LX, et al. Treatment guidelines of lymphatic malformations of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1105-1109.

- Elluru RG, Balakrishnan K, Padua HM. Lymphatic malformations: diagnosis and management. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23:178-185.

- Reinglas J, Ramphal R, Bromwich M. The successful management of diffuse lymphangiomatosis using sirolimus: a case report. The Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1851-1854.

- Molitch HI, Unger EC, Witte CL, vanSonnenberg E. Percutaneous sclerotherapy of lymphangiomas. Radiology. 1995;194:343-347.

- Acevedo JL, Shah RK, Brietzke SE. Nonsurgical therapies for lymphangiomas: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:418-424.

- Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, Nelson S, Lucky A, Elluru R, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1018-1024.

- Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005;37:19-24.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Google Scholar for

|

|

|

Article Statistics |

|

Altawil L, Neel NF, Alhedyani A, Badran M, Alokaili R, AlAjlan SNeutropenia in Sirolimus Treated Patients of Lymphatic Malformation: A Case Series.JCR 2017;7:169-173 |

|

Altawil L, Neel NF, Alhedyani A, Badran M, Alokaili R, AlAjlan SNeutropenia in Sirolimus Treated Patients of Lymphatic Malformation: A Case Series.JCR [serial online] 2017[cited 2024 Apr 27];7:169-173. Available from: http://www.casereports.in/articles/7/2/Neutropenia-in-Sirolimus-Treated-Patients-of-Lymphatic-Malformation.html |

|

|

|

|

|