6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff2886180000000b06000001000100

6go6ckt5b5idvals|750

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

The word bezoar is derived from the Persian language, which means “protection from the poison”. Historically, bezoars were believed to have the power of a universal antidote against any poison. A bezoar is persistent, ingested material that collects within the gastrointestinal tract. They are retained concretions of undigested matter that accumulate within the stomach and may subsequently migrate to distal parts of the GIT. Bezoars can be made of up vegetable or fruit fibers (phytobezoars), milk curds (lactobezoars) or any indigestible material that is ingested. Trichobezoars are composed usually of swallowed hair, which in many cases is the patient’s own, but also may be a variety of fibers from blankets, doll’s hair, animal hair, or carpet fibers. Patients with trichobezoar often remain asymptomatic for many years and remain so until the bezoar increases in size to the point of obstruction. Most patients with trichobezoar suffer from psychiatric disorders including trichotillomania (pulling out of their own hair) and trichophagia (eating of hair). It has been estimated that only 1% of patients with trichophagia develop a trichobezoar. We discuss such a case of a patient with trichophagia developing a trichobezoar.

Case Report

A 12 year old girl presented to our outpatient department with complaints of upper abdominal pain and vomiting since 15 days. Pain was more in the epigastric region, colicky in nature, non-radiating, and increased in intensity after meals. Her pain used to subside after vomiting, which contained undigested food particles. She had history of fullness of abdomen after meals and decreased appetite. She had no history of fever, symptoms of acid reflux, altered bowel motility, blood in stools, hematemesis, anxiety or any stressors. Her mother mentioned that the she had a history of eating hair, papers and chalk sticks since 4 years, but since past 6 months there has been no episode of such eating habits. She hadn’t taken any treatment for the habits.

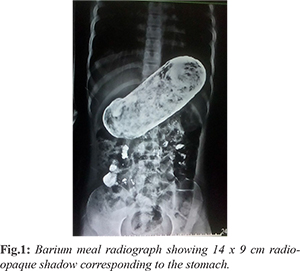

The patient had normal development and had stable vital signs. There was pallor noted with alopecia involving the frontal part of the head. Per abdomen examination revealed a firm, non-mobile 5” x 4” lump in the epigastrium, extending to left hypochondrium. Other systemic examinations were within normal limits. Laboratory evaluations revealed total leukocyte count of 4800/cmm., and hemoglobin of 10 gm/dL. Other laboratory investigations including serum electrolytes, creatinine and blood urea were within normal limits. Ultrasonography was suggestive of partial gastric outlet obstruction due to a heterogeneous mass in the stomach. A barium swallow showed radio-opaque shadow measuring 14 x 9 cm in the stomach suggestive of bezoar in gastric lumen [Fig.1].

An exploratory laparotomy was performed with a transverse incision in the epigastric region [Fig.2]. An anterior gastrostomy was done between two stay sutures. There was evidence of a large foreign body in the stomach which wasn’t adherent to the gastric mucosa. The 15 x 10 cm mass was found to a be trichobezoar and was removed [Fig.3,4]. After giving a thorough gastric wash stomach was closed in two layers. Post-operatively patient recovered well. She was kept nil by mouth for five days and then gradually allowed oral intake. A psychiatric evaluation was done post-operatively. As patient didn’t have recent history of ingestion of hair, papers etc. she was advised regular follow-up.

Discussion

A bezoar is persistent, ingested material that collects within the gastrointestinal tract. They are retained concretions of undigested matter that accumulate within the stomach and may subsequently migrate to distal parts of the GIT [1]. The first report of a trichobezoar dates back to the 18th century, when Baudamant described a 16-year-old boy with this condition [2]. The word bezoar is derived from the Persian language, which means “protection from the poison.” Historically, bezoars were believed to have the power of a universal antidote against any poison [3].

Bezoars can be made divided into three types. Phytobezoar, they are made up of vegetable or fruit fibres, lactobezoar, made up of milk curds and trichobezoar, made up of human hair. A gastric trichobezoar, is the most common type of bezoar and found in the stomach [4]. Trichobezoars are composed usually of swallowed hair, forms when hair strands, escaping gastric peristaltic propulsion are enmeshed into a ball. As this ball gets too large to leave the stomach, gastric atony may result. The mass is usually black because of the acidic nature of the stomach that denatures the proteins. Patients often have a foul smelling breath odour because of the decomposition and fermentation of fats [4].

Patients with trichobezoar often remain asymptomatic for many years and remain so until the bezoar increases in size to the point of obstruction [4]. The clinical features depend on which part of the gastrointestinal tract is involved [1]. Severe halitosis and patchy alopecia provide clues on physical examination [5]. Complications by a large eroding or obstructing bezoar additionally include gastric ulceration, obstructive jaundice, acute pancreatitis and gastric emphysema [6,7]. Other malabsorption related complications include protein-losing enteropathy, iron deficiency, and megaloblastic anemia. Bezoar is an easily missed diagnosis especially in the mentally retarded young patients. Most patients with trichobezoar suffer from psychiatric disorders including trichotillomania (pulling out of their own hair) and trichophagia (eating of hair). It has been estimated that only 1% of patients with trichophagia develop a trichobezoar [5]. Growth parameters should be measured to evaluate any malnutrition or stunted growth [8].

Radiologic investigations include abdominal radiography to reveal any distended gastric antrum, with associated dilated small bowel loop (Rapunzel Syndrome), and chest radiography to reveal any air under the diaphragm signifying intestinal perforation. Ultrasound abdomen and computerized tomography can be performed to evaluate the nature, size, and position of the mass [8,9]. Endoscopy is the diagnostic technique of choice for gastric and esophageal bezoars and has therapeutic potentials [1]. Endoscopy can help a surgeon distinguish between a trichobezoar and another foreign body that can be broken apart and removed endoscopically [10].

The advent of minimally invasive surgical techniques has increased the number of laparoscopic attempts to remove trichobezoars, but these procedures are often difficult. Advantages of laparoscopic removal are an improved cosmetic appearance, fewer postoperative complications, and reduced hospital stay [10]. Laparoscopic removal of an entire bezoar is difficult without spillage of hairs into the peritoneal cavity [11]. Open surgery is the most common technique used for trichobezoar removal. Some physicians consider conventional laparotomy to be the treatment of choice [10]. Surgical removal is accomplished by gastrotomy or enterotomy [5]. After the trichobezoar has been removed by laparotomy, it is essential to explore the remainder of the small intestine and stomach to look for any retained bezoars [12].

Bezoars have a tendency to recur in up to 14% of patients [13]. Treatment of underlying predisposing condition, increased water intake, diet alteration (eg, avoid persimmons and stringy vegetables) in case of phytobezoars, to chew food carefully, psychiatric evaluation for trichobezoars and counseling are part of treatment to prevent recurrence [3].

Conclusion

Trichobezoar should be considered in young females presenting with non-specific abdominal complaints.

Contributors: MA: study conception, operating surgeon and critical revision of manuscript; QSS: patient management and manuscript writing; PYB: critical revision of manuscript. QSS will act as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Ibuowo AA, Saad A, Okonkwo T. Giant gastric trichobezoar in a young female. Int J Surg. 2008;6:4-6.

- Fallon SC, Slater BJ, Larimer EL, Brandt ML, Lopez ME. The surgical management of Rapunzel syndrome: A case series and literature review. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:830-834.

- Hisamuddin K, Brandt CP. Hairball in the Stomach: A case of gastric trichobezoar. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1000-1001.

- Phillips JD. Rapunzel syndrome in a pediatric patient: A Case Report. AANA Journal. 2012;80(2):115-119.

- Gonuguntla V, Joshi DD. Rapunzel syndrome: A comprehensive review of an unusual case of trichobezoar. Clin Med Res. 2009;7:99-102.

- Jiledar Singh G, Mitra SK. Gastric perforation secondary to recurrent trichobezoar. Indian J Pediatr. 1996;63:689-691.

- Klipfel AA, Kessler E, Schein M. Rapunzel syndrome causing gastric emphysema and small bowel obstruction. Surgery. 2003;133:120-121.

- Hon KLE, Cheng J, Chow CM, Cheung HM, Cheung KL, Tam YH, et al. Complications of bezoar in children: what is new? Case Rep Pediatr. 2013;2013:523569.

- Ripollés T, García-Aguayo J, Martínez MJ, Gil P. Gastrointestinal bezoars: Sonographic and CT characteristics. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:65-69.

- Gorter RR, Kneepkens CMF, Mattens ECJL, Aronson DC, Heij HA. Management of trichobezoar: Case report and literature review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:457-463.

- Fraser JD, Leys CM, Shawn D. Laparoscopic removal of a gastric trichobezoar in a pediatric patient. Laparoendosc. 2009;19:835-837.

- Taori K, Deshmukh A, Rathod J, Sheorain V, Sanyal R. Rapunzel syndrome: a trichobezoar extending into the ileum. Appl Radiol. 2008;3:34-35.

- Ripollés T, García-Aguayo J, Martínez MJ, Gil P. Gastrointestinal Bezoars. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:65-69.