|

|

|

|

|

Sero-Negative Neuromyelitis Optica

|

|

|

venlafaxine alcohol side effects venlafaxine alcohol craving exlim.net Neeta Bhargava1, Vaishali Upadhayaya2, Rahul Dixit1, Suveer Bhargava3 Departments of 1Pediatrics and 2Radiodiagnosis, Vivekananda Polyclinic & Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow-226017; 3Department of Surgery, 92 Base Hospital, C/o 56 APO India. |

|

|

|

|

|

Corresponding Author:

|

|

Dr. Rahul Dixit Email: drrahuldixit86@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received:

03-APR-2017 |

Accepted:

17-JUN-2017 |

Published Online:

15-JUL-2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

|

|

|

|

Background: Neuromyelitis optica (NMO, Devic’s syndrome) is an immune mediated inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system that predominantly affects the spinal cord and optic nerves. Often confused with multiple sclerosis (MS), early diagnosis and differentiation from MS is important because of different treatment regimens. Case Report: We hereby report a sero-negative mono-phasic manifestation of this rare disease in a nine year old Indian boy. NMO was diagnosed in our case despite being sero-negative because of typical clinical findings and evidence of myelitis and optic neuritis seen in MRI. Patient was treated with pulse methyl-prednisolone followed by oral prednisolone and patient improved with some residual deformity. Conclusion: High index of suspicion is required to diagnose and treat patients at an early stage to prevent co-morbidities and complications. |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

Methylprednisolone, Myelitis, Neuromyelitis Optica, Optic Neuritis, Optic Nerve.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff247a1a0000008304000001001100 6go6ckt5b5idvals|771 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is a rare autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating condition with high female preponderance [ 1]. Initially considered a subtype of multiple sclerosis (MS), NMO is now considered a separate entity in itself especially after the discovery of a specific antibody NMO IgG in 2004 (now found to be anti-aquaporin4 IgG) [ 2]. Since then the diagnostic criteria has been revised multiple times with recent change in nomenclature to Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD) to incorporate sero-negative cases of NMO with strongly suggestive clinical and radiological findings [ 3].

The prevalence of the disease though low, its importance can’t be understated as it is more prevalent in Blacks and Asians populations [ 4]. Also, cases of sero-negative NMO are quite different from those of sero-positive NMO as they present with concurrent acute myelitis and optic nerve involvement with mono-phasic presentation and lesser female preponderance [ 5]. Nevertheless it’s important to have an early diagnosis and differentiation from MS, more so because of the high incidence of relapse in NMO and even deterioration in NMO in response to MS modifying treatment [ 6].

Case Report

We present a case of nine-year-old boy, third child of a non-consanguineous marriage, who developed high grade fever with headache and body-ache of one day duration. This was followed by urinary retention, weakness of both lower limb which gradually progressed to total loss of power in both lower limbs and altered sensorium. During initial hospitalization his sensorium improved but he developed diminution of vision. He was referred to our institute after 17 days of onset of illness. He had complete blindness, with total paraplegia, loss of both bowel and bladder control. There was no history of seizure, vomiting, rashes, and no history of similar episodes in past. The child was fully immunized.

On examination child was fully conscious, speech was normal, and was able to eat and drink normally but did not have bladder and bowel control. He had total blindness with no perception of light. Vitals were stable, no cranial nerve deficit, there was decreased tone and 0/5 power in both lower limbs. Deep tendon reflexes and superficial reflexes were absent along with sensory level. Both upper limbs were normal. Rest of systemic examination was within normal limits.

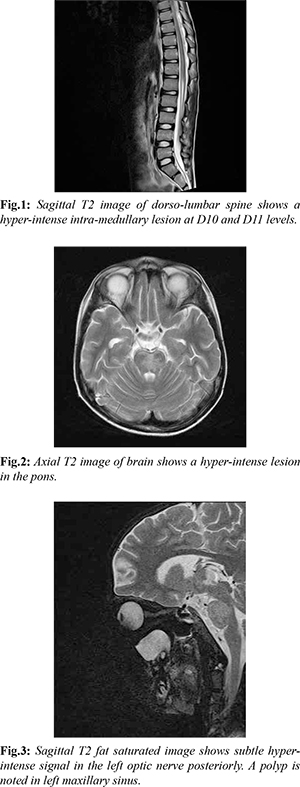

Blood investigations revealed mild anaemia with otherwise normal blood counts. Biochemical profile and CSF analysis were normal. MRI spine was done which revealed a T2 hyper-intense lesion in the lower cord at D10-D11 levels [Fig.1]. MRI brain with screening of optic nerves was also done and revealed hyper-intense lesion in pons and a subtle hyper-intensity in T2 FLAIR image in the left optic nerve posteriorly [Fig.2,3]. Considering the clinical profile of the patient, the possibility of demyelinating lesions due to NMOSD was suggested. It was thought that delayed imaging was responsible for the short segment lesion in the spinal cord.

CSF sample for NMO-IgG was sent but it came out to be negative. Nevertheless, patient was treated on lines of NMOSD and was started on methyl-prednisolone intravenously as pulse therapy at 30 mg/kg/day once a day for three days followed by oral prednisolone at 7 mg/kg/day for six weeks in tapering doses. Along with steroids, multivitamins especially vitamin B12 was given. Over a course of next few weeks, patient’s vision improved and he regained his vision completely, there was gain in power in both lower limbs along with bowel and bladder control. Over a two year follow up, the patient was found to have spasticity in both lower limbs and was ambulant.

Discussion

The first description of a co-existence between acute myelitis and optic nerve involvement was reported in 1870 by Albutt [ 7]. Eugène Devic in 1884, reported a 45-year-old woman with symptoms of headache and malaise followed by development of urinary retention, complete paraplegia and blindness. Devic named the syndrome “neuro-myélite optique”. This led to discovery of a new disease entity which almost 30 years later was named after him as “Devic’s disease” [ 7].

Pathophysiology involves interaction of NMO IgG’s with aquaporin 4 (ACQ4) leading to lysis of astrocytes [ 11]. The clinical presentation of NMO can begin with either isolated myelitis or optic nerve involvement or they can occur simultaneously in a presentation. Acute myelitis presents with mild sensory involvement to paraplegia with bladder bowel dysfunction [ 8]. NMO has a usual relapsing course without marked progression of disability in between two episodes of relapse, but rarely, it can have a monophasic (15-23%) or secondary chronic progressive (2%) course [ 3, 8, 9]. Occurrence of residual deficit and steep advancement of disease is commonly seen.

The classical description includes CSF pleocytosis with elevated CSF proteins. MRI is the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of patients with suspected NMO. MRI reveals T2 hyper-intense lesions extending over three or more vertebral segments in spinal cord. These longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions (LESCLs) are commoner in AQP4 positive patients than those who are negative for the antibody and patient may show short segment T2 hyper-intense lesions on imaging. Delayed imaging after the beginning of symptoms may also result in short segment lesions [ 12, 13].

In the brain, peri-ependymal lesions at the level of third ventricle, aqueduct and fourth ventricle are characteristic in patients who are positive for AQP4 antibody. The optic nerves may show bilateral involvement, altered signal intensity with posterior extension into the optic chiasma and contrast enhancement [ 12, 13]. In the acute phase, pulse dose methyl-prednisolone therapy is the treatment of choice followed by tapering dose of oral steroid for 2-6 months. In resistant cases or those worsening on steroid, plasmapheresis, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, mitoxantrone, rituximab or cyclophosphamide has shown a promising role [ 14].

The disease can have monophasic course with complete remission or polyphasic course with repeated incidents of optic neuritis and transverse myelitis. There can be permanent visual loss in as many as 60% patients, and permanent paralysis (unilateral or bilateral) in 52% patients in those having relapsing course of disease. In some patients, involvement of cervical spinal cord may lead to respiratory muscle involvement and subsequently death due to respiratory failure [ 8].

Conclusion

NMO as a disease is a rare entity in pediatric age group. Still a high index of suspicion is essential to catch as well as treat the patients at an early stage to prevent co-morbidities and complications.

Contributors: NB, RD: manuscript writing, literature search and case management; VU, SB: manuscript editing and critical inputs into the manuscript. RD will act as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References - Mealy MA, Wingerchuk DM, Greenberg BM, Levy M. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica in the United States: A multicenter analysis epidemiology of NMO. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1176-1180.

- Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Fujihara K, et al. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: Distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2004;364:2106-2112.

- Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, Cabre P, Carroll W, Chitnis T, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015;85:177-189.

- Jacob A, Boggild M. Neuromyelitis optica. Pract Neurol. 2006;6:180-184.

- Marignier R, Bernard-Valnet R, Giraudon P, Collongues N, Papeix C, Zéphir H, et al. NOMADMUS Study Group: Aquaporin-4 antibody-negative neuromyelitis optica: distinct assay sensitivity-dependent entity. Neurology. 2013;80:2194-2200.

- Palace J, Leite MI, Nairne A, Vincent A. Interferon beta treatment in neuromyelitis optica: Increase in relapses and aquaporin 4 antibody titres. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1016-1017.

- Peixoto MA. Devic’s Neuromyelitis Optica. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66:120-138.

- Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, Weinshenker BG. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurology. 1999;53:1107-1114.

- Sven J, Friedemann P, Diego F, Patrick W, Frauke Z, Reinhard H, et al. Mechanisms of Disease: aquaporin-4 antibodies in neuromyelitis optica. Nature. 2008;4:4.

- Verkman, AS. More than just water channels: Unexpected cellular roles of aquaporins. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3225-3232.

- Kinoshita M, Nakatsuji Y, Moriya M, Okuno T, Kumanogoh A, Nakano M, et al. Astrocytic necrosis is induced by anti-aquaporin-4 antibody-positive serum. Neuroreport. 2009;20:508-512.

- Barnett Y, Sutton I J, Ghadiri M, Masters L, Zivadinov R, Barnett MH. Conventional and advanced imaging in neuromyelitis optica. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1458-1466.

- Downer JJ, Liete MI, Carter R, Palace J, Kuker W, Quaghebeur G. Diagnosis of Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) spectrum disorder: Is MRI Obsolete? Neuroradiol. 2012;54:279-285.

- Kimbrough DJ, Fujihara K, Jacob A, Lana-Peixoto MA, Leite MI, Levy M, et al. Treatment of neuromyelitis optica: Review and recommendations. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2012;1:180-187.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Google Scholar for

|

|

|

Article Statistics |

|

Bhargava N, Upadhayaya V, Dixit R, Bhargava SSero-Negative Neuromyelitis Optica.JCR 2017;7:250-253 |

|

Bhargava N, Upadhayaya V, Dixit R, Bhargava SSero-Negative Neuromyelitis Optica.JCR [serial online] 2017[cited 2024 Apr 24];7:250-253. Available from: http://www.casereports.in/articles/7/3/Sero-Negative-Neuromyelitis-Optica.html |

|

|

|

|

|