6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff64871d0000005e07000001000700

6go6ckt5b5idvals|804

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Critical stenosis of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) is a comparatively uncommon, however an important cause of coronary artery disease (CAD) with poor prognosis [

1]. Such an occurrence happening in adolescents is much more uncommon [

2] and it is a real challenge in establishing the correct diagnosis and management as in adults. We report an unusual case of a 14 year old girl presenting with acute LMCA occlusion which was successfully treated with percutaneous coronary intervention.

Case Report

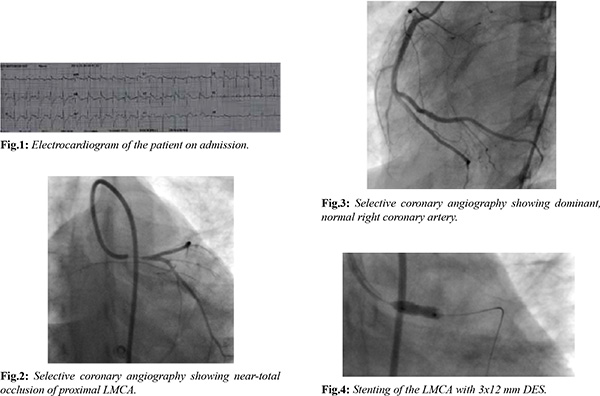

A 14 year old girl was transferred to the Department of Cardiology, Teaching Hospital Kandy, Sri Lanka following an acute extensive anterior myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. She had developed sudden onset severe retrosternal chest pain which was associated with autonomic symptoms lasting for more than two hours before admission to the local hospital. The pain had developed at rest and following the event, she was found to be unconscious at home. In the emergency department at the local hospital, her electrocardiogram showed elevated ST segments in leads I, aVL and V1-V6 with reciprocal changes in the inferior leads [Fig.1]. On admission, she was hypotensive (BP 80/50 mmHg) and had pulmonary edema (Killip class IV). On arrival to our institution, she was supported with intravenous dobutamine and nor-adrenaline infusions. Loading doses of aspirin, clopidogrel and single dose of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin had been administered at the local hospital, though she was not given any thrombolytics.

She had given a history of exertional dyspnea with exercise limitation in the last few months without having angina. She had no history of known cardiac disease, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia or known autoimmune rheumatological disease. There was no family history of premature CAD and had no significant exposure to active or passive cigarette smoking. Physical examination showed no evidence of xanthalesma, stigmata of connective tissue disease, bruie or asymmetrical peripheral pulses.

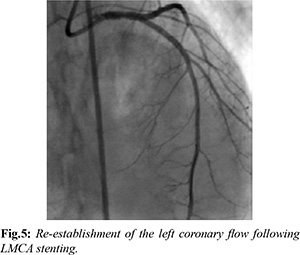

Her two dimensional (2D) echocardiogram on admission showed anterior wall hypokinesia and left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction of 30% without apical ballooning. Selective left and right coronary angiography was performed through femoral arterial approach using left Judking’s 3 (JL 3) and right Judking’s 3.0 (JL 3) diagnostic coronary catheters. It showed near total occlusion of the proximal LMCA with thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) I to II flow in left anterior descending (LAD) and left circumflex (LCX) arteries with no obstructive lesions beyond the left main stem [Fig.2]. Right coronary artery was normal and dominant without having collaterals to left system [Fig.3]. No coronary artery aneurysms were noted during angiography. Root aortogram excluded the proximal aortic dissections. LMCA engaged with left Judking’s 3 guiding catheter and the lesion was crossed with floppy guide wire. The lesion was pre-dilated with 2.25 × 10 mm semi-compliant balloon at 8 atmospheres (atm) pressure. The lesion was stented with 3 × 12 mm Evarolimus Drug Eluting Stent (DES) at 10 atm pressure. The stent was post dilated with 3.5 × 10 mm non-compliant balloon at 20 atm [Fig.4]. During the post-dilatation, a tight area was noted in the osteo-proximal segment of LMCA which was unusual in pure acute thrombotic occlusion. TIMI III flow was noted in LMCA and its branches following the stenting [Fig.5].

The procedure was performed under local anesthesia with conscious sedation. The patient was electively intubated and ventilated following the coronary intervention with intravenous inotropic and diuretic support. Following PCI she showed marked improvement with reduced inotropic support and improvement of LV function. She was extubated at the end of 48 hours of ventilation and discharged on the 7th day of PCI with dual antiplatelet therapy and maximum medical support.

Laboratory tests on presentation were normal except for high ESR (53 mm in 1st hour). During subsequent follow up she was extensively investigated for a course for LMCA stenosis. She had normal blood counts, clotting profile and normal lipid profile. Her liver functions, serum proteins and renal profile were normal. Computed Tomography (CT) aortogram showed no evidence of Takayasus’ arteritis. Her CT pulmonary angiogram also became normal excluding type IV Takayasus’ arteries. Autoimmune screen including anti-phospholipid antibodies, anti-nuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, C & P anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. She had normal hemoglobin electrophoresis and negative tests for human leucocyte antigen-B52. She also had negative tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and venereal disease research laboratory test. She also had normal homocystine levels and negative thrombophilia screening.

Her ESR was found to be persistently elevated and she was treated with oral steroids (30 mg of prednisolone daily) as clinical suspicion of atypical presentation of Takayasus’ arteritis was high. Her LV function showed improvement up to 50% at the end of 4th week following intervention. During further follow up she showed good symptomatic improvement achieving better exercise tolerance at the end of 8th week following discharge.

Discussion

Coronary artery disease involving LMCA is rare during childhood and adolescence [

2]. Congenital partial or complete coronary ostial stenosis or atresia (COSA), atherosclerosis (familial hyperlipidemia), Kawasaki disease, Takayasu aortitis, and syphilis are some of the causes for this rare condition [

1-

8]. In our patient, other than persistent elevation of ESR, no other abnormalities were found in the investigations suggestive of specific type of vasculitis. The empirical steroid treatment was initiated with a high degree of suspicion of atypical Takayasu aortitis though other clinical criteria for this specific diagnosis is lacking.

PCI and stenting are technically demanding treatment options in children and adolescents due to procedural difficulties and possible complications [

9]. Potential technical difficulties include non-cooperation of the patient and need of anesthesia, lack of availability of suitable hardware and potential adverse effects related to pharmacotherapy. In our patient the selective engagement of the left coronary ostium was challenging even with JL3 guiding catheter due to short curvature of the aortic arch. In addition, the pressure dampening while attempting to engage the coronary ostium with a tight stenosis of the LMCA was also technically demanding.

Another concern in this age group is that the stent may hinder the native growth of the intervene segment. Determining the exact nature and extent of the disease as well as the adequate expansion of the stent are some of the important technical consideration of the procedure in this patient. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) would have been extremely useful [

7] in this situation but it was not performed as the facility was not available in our catheterization laboratory at that time. However, this type of urgent coronary intervention with DES may be lifesaving even without pre-procedural IVUS assessment in a resources poor setting. The appropriateness of bio-absorbable vascular scaffold should also to be considered in this context since it may not hinder the natural growth of the coronary system in long term.

The stent thrombosis and re-stenosis are possible complications to be considered in this patient as there was mild under expansion of the osteo- proximal segment of the stent, despite post dilating up to higher pressures (20 atm). Adherence to dual anti-platelet therapy is very crucial in this patient but there may be issues pertained to compliance of drug treatment in a child. The optimal duration of dual anti-platelet therapy is also a matter to be addressed in this age group as there are no widely available evidences to guide the treatment.

Conclusion

Though the definite diagnosis of this patient is a dilemma, the immunosuppressive treatment was initiated to cover the possible coronary vasculits through COSA is one of the possibility in this situation. Here we suggest that PCI would be a promising intervention for acute total or subtotal occlusion of LMCA even in adolescents [6] in a background of unstable clinical setting, though it is technically challenging.

Contributors: AK, TSS, HGWAPLB: manuscript writing, intervention procedure of patient; GM, TK, AJ: manuscript editing, initial diagnosis and management; NWK, WMGW, SRJ, SNBD: critical inputs into the manuscript, and cardiac rehabilitation. HGWAPLB will act as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Angelini P. Congenital coronary artery ostial disease: A spectrum of anatomic variants with different pathophysiologies and prognoses. Texas Hear Inst J. 2012;39:55-59.

- Blieden LC, Neufeld HN, Coronary artery disease in children. Postgrad Med J. 1978;54:163-169.

- Bulut S, Al Hashimi HMM, Verheugt FWA. Left main stem disease in a patient with Takayasu’s arteritis. Neth Heart J. 2007;15:260-262.

- Vikas K, Sachdev MS, Vipul R, Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty following Kawasaki disease. Indian Pediatrics. 2011;48;233-235.

- Cohen MV, Sum M. Main left coronary artery disease Clinical experience from 1964-1974. Circulation. 1975;52:275-285.

- Li J-J, Xu B, Chen J-L. Stenting for left main coronary artery occlusion in adolescent: A case report. World J Cardiol. 2010;2:211-214.

- Nakatani S, Yamagishi M, Tamai J, Goto Y, Umeno T, Kawaguchi A, et al. Assessment of coronary artery distensibility by intravascular ultrasound. Application of simultaneous measurements of luminal area and pressure. Circulation. 1995;91:2904-2910.

- Nakazone MA, Machado MN, Barbosa RB, Santos MA, Maia LN. Syphilitic coronary artery ostial stenosis resulting in acute myocardial infarction treated by percutaneous coronary intervention. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010:830583.

- Sugimura T, Yokoi H, Sato N, Akagi T, Kimura T, Iemura M, et al. Interventional treatment for children with severe coronary artery stenosis with calcification after long-term Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 1997;96:3928-3933.

- Wieman R, Beelen D, Van Der Zwaan C, Lahpor J, De Vos AM, Doevendans PA. Adolescent with occluded left main coronary artery. Neth Heart J. 2005;13:239-241.