|

|

|

|

|

Recurrent Ventricular Tachycardia due to Multiple Etiologies

|

|

|

|

Lal Hussain Mughal, Jeffery P Khoo Grantham and District Hospital, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Lincolnshire, UK. |

|

|

|

|

|

Corresponding Author:

|

|

Dr. Lal Hussain Mughal Email: lal.mughal7@gmail.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received:

27-NOV-2017 |

Accepted:

13-JAN-2018 |

Published Online:

30-JAN-2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

|

|

|

|

Background: Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is a life threatening arrhythmia in which an identification of the correct cause and its timely treatment is vital for the patient. Case Report: We present a case report of a 66 year man with recurrent episodes of sustained and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) confirmed through telemetry on a background of excessive ventricular ectopic activity. Surprisingly, he had different triggers for his ventricular tachycardia (VT) on each presentation to the hospital which settled with anti-arrhythmic drugs and treating the underlying cause. Conclusion: The reason for reporting this case is to highlight rare triggers of VT (a life threatening arrhythmia) and that it is important to keep on looking for other aetiologies especially if VT recurs after satisfactory treatment of an earlier cause as in this case. |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

Anti-Arrhythmia Agents, Telemetry, Ventricular Tachycardia, Ventricular Premature Complexes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff647b1f0000007407000001000200 6go6ckt5b5idvals|825 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is a life threatening/malignant arrhythmia with a myriad of underlying etiologies. Overall VT accounts for 5.6% of all mortality. However in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and non-sustained VT, sudden death mortality approaches up to 30% in two years. Morbidity from VT is associated with hemodynamic collapse. In this fatal arrhythmia an identification of the correct cause and its timely treatment is vital in the longer term management and prognosis of patients with this condition.

Case Report

A 66 year old retired gentleman had recently completed a course of neo-adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy with capecitabine for his colorectal cancer a month prior to his first presentation. He was a non-smoker and consumed about 15 units of alcohol (red wine) per week. He also had a long-standing history of hay fever. He did not take any regular medications and had no known drug allergies. Two years prior to his first presentation, he was seen by cardiology for intermittent palpitations. Exercise tolerance test and echocardiogram were normal. 24 hour Holter ECG, apart from excessive ventricular ectopic activity of around 11% of total duration of recording, did not show any other sustained arrhythmia at that point. A cardiac MRI performed to investigate for any structural heart disease in view of excessive ventricular ectopic activity was normal.

First Presentation:

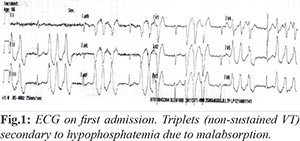

His first presentation was through emergency department with one week history of diarrhea and two days’ history of palpitations and dizziness. On examination, he appeared alert but mildly dehydrated. His pulse was irregular with HR of 70-120 bpm, blood pressure (BP) was 135/75 and rest of cardiovascular examination was unremarkable. His routine bloods (including serum electrolytes, renal functions, thyroid function tests) and urinary catecholamine levels were within normal range. His 12 lead ECG [Fig.1] showed unifocal ventricular ectopics with 3-6 beat runs of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. We then requested serum calcium, magnesium and phosphate levels and this revealed severe hypophosphatemia with serum phosphate levels of <0.21 mmol/L (reference range 0.74-1.5 mmol/L) and mildly raised Troponin I of 0.06 ng/mL (cut-off <0.01 ng/mL). His inpatient echocardiogram again revealed normal biventricular size and function. In view of his mildly raised Troponin I and ventricular arrhythmia a coronary angiogram was performed to exclude any underlying coronary artery disease which was reassuringly normal.

He was diagnosed as VT secondary to hypo-phosphatemia. He was treated with intravenous (IV) amiodarone and IV phosphate infusions. Within 12 hours of starting the regimen his VT episodes settled. An exercise tolerance test to look for any further stress induced arrhythmias was normal. His palpitations and dizziness had significantly improved and he was discharged home on sotalol 80 mg BD. A month following discharge from the hospital he underwent uncomplicated elective anterior resection for his colorectal cancer with loop ileostomy.

Second Presentation:

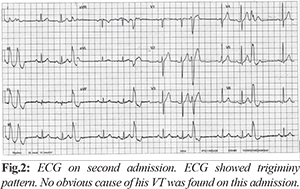

He had a routine review in cardiology clinic two months following his discharge from hospital. He mentioned further symptoms of palpitations and was re-admitted to CCU for observation and investigations to rule out any sustained ventricular arrhythmia. His physical examination was unremarkable and all bloods including phosphate were within normal limits. ECG [Fig.2] showed unifocal interpolated VE’s in trigeminal pattern with normal QTc. Whilst an inpatient he had further episode of sustained VT and given his recurrent VT, sotalol was switched to amiodarone. He was given a loading dose of IV amiodarone followed by oral amiodarone in reducing regimen with long term maintenance at 200 mg once daily. His palpitations improved, however, on that admission the cause for his ventricular arrhythmia remained unclear. He was discharged home and a repeat outpatient 24 hour tape was reassuringly normal without any ventricular ectopic activity. On further outpatient follow up, the patient remained stable and decided to come off amiodarone due issues of long term side-effects.

Third Presentation:

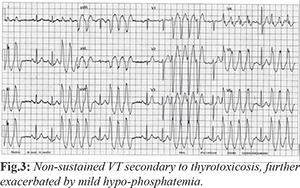

Three month following cessation of amiodarone patient was readmitted with diarrhoea and weight loss for 4 weeks and palpitations for one week. His ECG [Fig.3] was again suggestive of frequent triplets and non-sustained VT. On blood tests this time he was found to have hyperthyroidism with very low TSH of 0.01 mU/L, high T4 at 35.5 pmol/L and T3 at 9.73 pmol/L. He had mild hypo-phosphatemia with a level of 0.55 mmol/L. The thyroid peroxidise antibodies were negative but ultrasound scan was suggestive of thyroiditis. He was treated as non-sustained VT secondary to hyperthyroidism/thyroiditis. This was exacerbated by co-existing mild hypo-phosphatemia due to malabsorption secondary to his bowel malignancy. His arrhythmia settled with bisoprolol 2.5 mg once daily which was up-titrated to 5 mg OD before discharge and was also commenced on carbimazole for thyrotoxicosis. His hypo-phosphatemia was initially corrected with IV phosphate and then maintenance with oral phosphate replacement. He made a good recovery and was discharged home with further cardiology and endocrinology reviews as outpatients. His final diagnosis from endocrine team was primary thyrotoxicosis which eventually settled with carbimazole. Since amiodarone was stopped at least 3 months prior to developing symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, it was not thought to be directly contributing to this. However some studies have shown that its side effects can manifest several months after stopping it.

Patient had further one admission with chest pain and this time investigations were not suggestive of any arrhythmia or other cardiac event and his subsequent outpatient dobutamine stress study confirmed absence of stress related arrhythmia and ischemia. Regarding the excessive ventricular ectopic activity it was suggested that the gentleman routinely suffers from hay fever (which can lead to systemic histamine release). This combined with red wine that also contains histamine compounds could be a trigger of his frequent ventricular extra systoles. He is now on regular antihistamine medication and has not had any further VT episodes since.

Discussion

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is responsible for most of the sudden cardiac deaths. VT refers to any rhythm faster than 100 or more beats/min, with three or more successive irregular beats, arising distal to the bundle of His. The rhythm could be generated by the ventricular myocardium, the distal conduction system, or both. Common symptoms of VT are palpitations, light-headedness, syncope or chest pain. However, patient can be asymptomatic or the symptoms may be related to associated therapy like an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator [ICD] shock. Electrocardiography (ECG) is the standard test for the diagnosis of VT, However in hemodynamically unstable patients the diagnosis is made and ECG rhythm strip if available. Broadly speaking, the causes of VT can be (i) structural for example old MI or non-MI scar [1,2], ischemia/ACS [3], cardiomyopathies/ARVC [4], heart failure [5.6], (ii) electrical: long QT/ short QT/ Brugada syndromes, RVOT- VT (inferior axis and LBBB), catecholaminergic polymorphic VT (CPVT) [7,8]. (iii) extra-cardiac like electrolyte abnormalities (including hypo-magnesaemia and hypo-phosphatemia) [9-11], endocrine disorders especially thyrotoxicosis [12-14], histamine compounds [15,16], and various drugs [17,18]. Amiodarone in some cases can cause delayed thyroiditis leading to thyrotoxicosis [19]. In terms of treatment this could be medical or interventional. In medical treatment, anti-arrhythmic medications like amiodarone are useful option for treating VT [20-22]. However, amiodarone should not be used for VT related to prolonged QT interval [23]. Beta-blockers like bisoprolol as in this case are useful in suppressing ventricular arrhythmic ectopic activity and also providing symptomatic relief [24-26]. Sotalol is another option which apart from beta-blocker activity also acts as an anti-arrhythmic agent [27,28] but is contraindicated in patients with VT secondary to long QT syndrome. For long-term treatment of most patients with left ventricular dysfunction, current clinical practice favours class II (beta-blockers) and III antiarrhythmics (eg, amiodarone, and sotalol). As for as interventional treatment is concerned, various interventional approaches can be useful for useful for treating VT e.g. VT ablation is very effective for monomorphic/unifocal VT [29-31]. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) can be used to prevent VT related cardiac death for complex and congenital cases [32,33].

Conclusion

VT is a life threatening arrhythmia which has a number of underlying causes ranging from very common to rare and could be multi-factorial. Various episodes of VT in a single patient could be due various underlying causes on each presentation as in our case. Hence, a thorough assessment of patient on each presentation is vital as to not miss a treatable underlying cause as outcome could lead to grave consequences. Previously normal cardiac investigations do not exclude the possibility of future ventricular arrhythmia.

Contributors: LHM: Manuscript writing and patient management; JPK: manuscript editing and patient management. LHM will act as guarantor. Both authors approved the final version of this manuscript. Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References - Scott PA, Morgan JM, Carroll N, Murday DC, Roberts PR, Peebles CR, et al. The extent of left ventricular scar quantified by late gadolinium enhancement MRI is associated with spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2011;4:324-330.

- Zorzi A, Perazzolo Marra M, Rigato I, De Lazzari M, Susana A, et al. Nonischemic left ventricular scar as a substrate of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in competitive athletes. Circulation Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2016;29:486-496.

- Harkness JR, Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Ren F, Lopez-Sendon J, et al. Myocardial ischemia and ventricular tachycardia on continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and risk of cardiovascular outcomes after non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 Trial). The American Journal of Cardiology. 2011;108:1373-1381.

- Link MS, Laidlaw D, Polonsky B, Zareba W, McNitt S, Gear K, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias in the North American multidisciplinary study of ARVC: predictors, characteristics, and treatment. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;64:119-125.

- Chakko S, de Marchena E, Kessler KM, Myerburg RJ. Ventricular arrhythmias in congestive heart failure. Clinical Cardiology. 1989;12:525-530.

- Khoshnevis GR, Massumi A. Ventricular arrhythmias in congestive heart failure: clinical significance and management. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 1999;26:42-59.

- Bhar-Amato J, Nunn L, Lambiase P. A review of the mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmia in brugada syndrome. Indian pacing and Electrophysiology Journal. 2010;10:410-425.

- Siegers CEP, Visser M, Loh P, van der Heijden JF, Hassink RJ. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) initially diagnosed as idiopathic ventricular fibrillation: the importance of thorough diagnostic work-up and follow-up. International Journal of Cardiology. 2014;177:e81-83.

- Schwartz A, Brotfain E, Koyfman L Kutz R, Gruenbaum SE, Klein M, Zlotnik A, et al. Association between hypophosphatemia and cardiac arrhythmias in the early stage of sepsis: could phosphorus replacement treatment reduce the incidence of arrhythmias? Electrolyte & Blood Pressure. 2014;12:19-25.

- Venditti FJ, Marotta C, Panezai FR, Oldewurtel HA, Regan TJ. Hypophosphatemia and cardiac arrhythmias. Mineral and Electrolyte Metabolism. 1987;13:19-25.

- Etienne Y, Songy B, Guiserix J, Blanc JJ, Boschat J, Penther P. Treatment of torsades de pointes with magnesium sulfate. Presse Med. 1985;14:640.

- Nadkarni PJ, Sharma M, Zinsmeister B, Wartofsky L, Burman KD. Thyrotoxicosis-induced ventricular arrhythmias. Thyroid. 2008;18:1111-1114.

- Chandra PA, Vallakati A, Chandra AB, Pednekar M, Ghosh J. Repetitive monomorphic ventricular tachycardia as a manifestation of suboptimally treated thyrotoxicosis. The American Heart Hospital Journal. 2010;8:E113-114.

- Erdogan HI, Gul EE, Gok H, Nikus KC. Therapy-resistant ventricular tachycardia caused by amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis: a case report of electrical storm. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;30:2092.e5-7.

- Wolff AA, Levi R. Histamine and cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation Research 1986;58:1-16.

- Marra L, Bevilacqua E, Carella G. Excess of histamine as a possible cause of cardiac arrhythmias. La Clinica terapeutica. 1996;147:145-147.

- Kundu S, Williams SR, Nordt SP, Clark RF. Clarithromycin-induced ventricular tachycardia. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1997;30:542-544.

- Vallejo Camazon N, Rodriguez Pardo D, Sanchez Hidalgo A, Tornos Mas MP, Ribera E, Soler Soler J. Ventricular tachycardia and long QT associated with clarithromycin administration in a patient with HIV infection. Revista espanola de cardiologia. 2002;55:878-881.

- Pillarisetti J, Vanga SR, Lakkireddy D. Amiodarone induced thyrotoxicosis - fluctuating RVOT and LV Scar VT. J Atr Fibrillation. 2013;5:342.

- Ward DE, Camm AJ, Wang R, Dymond D, Spurrell RA. Suppression of long-standing incessant ventricular tachycardia by amiodarone. Journal of Electrocardiology. 1980;13:193-198.

- Kaski JC, Girotti LA, Messuti H, Rutitzky B, Rosenbaum MB. Long-term management of sustained, recurrent, symptomatic ventricular tachycardia with amiodarone. Circulation. 1981;64:273-279.

- Mattison P, Rodger JC. Rapid control of recurrent ventricular tachycardia with oral amiodarone. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed). 1982;285:939-940.

- Di Micoli A, Zambruni A, Bracci E, et al. "Torsade de pointes" during amiodarone infusion in a cirrhotic woman with a prolonged QT interval. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:535-538.

- Tonet J, Frank R, Fontaine G, Grosgogeat Y. Efficacy and safety of low doses of beta-blocker agents combined with amiodarone in refractory ventricular tachycardia. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology: PACE. 1988;11:1984-1989.

- 25. Exner DV, Reiffel JA, Epstein AE, Ledingham R, Reiter MJ, Yao Q, et al. Beta-blocker use and survival in patients with ventricular fibrillation or symptomatic ventricular tachycardia: the Antiarrhythmics versus implantable defibrillators (AVID) trial. American Journal of Cardiology. 1999;34:325-333.

- van der Werf C, Lieve KV. Beta-blockers in the treatment of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:441-442.

- Kus T, Campa MA, Nadeau R, Dubuc M, Kaltenbrunner W, Shenasa M. Efficacy and electrophysiologic effects of oral sotalol in patients with sustained ventricular tachycardia caused by coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal. 1992;123:82-89.

- Hoffmann E, Mattke S, Haberl R, Steinbeck G. Randomized crossover comparison of the electrophysiologic and antiarrhythmic efficacy of oral cibenzoline and sotalol for sustained ventricular tachycardia. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1993;21:95-100.

- Bansch D, Schneider R, Akin I, Nienaber CA. VT ablation in heart failure. Herzschrittmachertherapie & Elektrophysiologie. 2012;23:38-44.

- Tung R, Josephson ME, Reddy V, Reynolds MR, Investigators SV. Influence of clinical and procedural predictors on ventricular tachycardia ablation outcomes: an analysis from the substrate mapping and ablation in Sinus Rhythm to Halt Ventricular Tachycardia Trial (SMASH-VT). Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2010;21:799-803.

- Tanner H, Hindricks G, Volkmer M, Furniss S, Kühlkamp V, Lacroix D, et al. Catheter ablation of recurrent scar-related ventricular tachycardia using electroanatomical mapping and irrigated ablation technology: results of the prospective multicenter Euro-VT-study. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2010;21:47-53.

- Akhtar M, Jazayeri M, Sra J Jazayeri MR, Dhala A, Blanck Z, Deshpande S, et al. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator for prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation: ICD therapy in sudden cardiac death. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology: PACE. 1993;16:511-518.

- Siebels J, Schneider MA, Kuck KH. Low energy cardioversion with the implantable cardioversion defibrillator devices for treatment of ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. Z Kardiol. 1993;82:683-691.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Search Google Scholar for

|

|

|

Article Statistics |

|

Mughal LH, Khoo JPRecurrent Ventricular Tachycardia due to Multiple Etiologies.JCR 2018;8:33-37 |

|

Mughal LH, Khoo JPRecurrent Ventricular Tachycardia due to Multiple Etiologies.JCR [serial online] 2018[cited 2026 Jan 9];8:33-37. Available from: http://www.casereports.in/articles/8/1/Recurrent-Ventricular-Tachycardia-due-to-Multiple-Etiologies.html |

|

|

|

|

|