6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ffec2423000000ff06000001000900

6go6ckt5b5idvals|870

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Meconium peritonitis is a rare prenatal disease with high rate of morbidity and mortality. Antenatal and postnatal ultrasound may show abdominal calcifications, ascites, polyhydramnios, echogenic mass and dilated bowel or intestinal obstruction. We want to report this case as meconium peritonitis should be considered as one of the possibilities of ascites in a newborn and at times can be managed conservatively.

Case Report

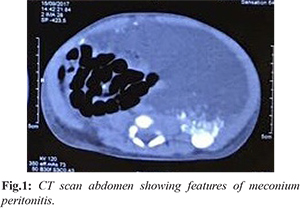

A 2.6 kg four-day-old male infant was brought to the emergency department for an increased work of breathing, accompanied by decreased oral intake since birth. The mother reported that the child’s symptoms started soon after birth along with abdominal distension [Fig.1]. Baby had respiratory distress soon after birth with abdominal distension. The baby was born at full term by vaginal delivery to G3P2 mother with APGAR score of 9, 10, 10. Antenatal scan had showed polyhydramnios, and lesion measuring 7.6×6.9 cms, with irregular margin within the fetal abdomen, pushing the stomach and bowel loops suggestive of dermoid cyst or loculated collection. He was started on oxygen in view of respiratory distress due to abdominal distension, and continued on intravenous fluids. Empirical antibiotic therapy started for suspected neonatal sepsis was stopped after negative septic screen. Liver function tests and renal function tests were within normal limits. Ultrasound abdomen showed edematous gallbladder wall with moderate to gross ascites.

Monitoring of abdominal girth measurements showed no increase. Respiratory distress settled gradually and hence oxygen could be weaned. The baby had passed meconium at birth, passing stools normally with no vomiting and signs of intestinal obstruction. Trophic feeds were started which were gradually graded up to full oral feeds and later to direct breast feeds which baby tolerated well. In view of persistent abdominal distention CT scan abdomen [Fig.2,3] was done which showed moderate ascites with multiple calcifications extending into both scrotal sacs, likely meconium peritonitis. In our case calcifications were not visible in X ray or in ultrasonogram of abdomen and required CT scan abdomen for detection.

Pediatric surgeon consultation was sought who advised no surgical intervention and only conservative management. Baby was discharged on 14th day of life and is doing well on follow up at 40 days of life.

Discussion

Meconium peritonitis was first detected by Morgagni in 1761, but the first surgical correction was performed successfully in 1943 by Agerty [1]. In rare cases, chemical peritonitis heals spontaneously without any clinical manifestations. Attention to this pathology was drawn by findings presented as calcifications, intra-peritoneal, inguinal or scrotal masses [2]. The incidence of meconium peritonitis is about 1:30,000 [3]. Perinatal morbidity and mortality is about 80%. In the case of meconium peritonitis, the incidence of prematurity is 20-30 %. Due to improved neonatal intensive care has resulted in a 10% decrease in mortality [4].

Infants usually present with tense abdominal distension, edematous wall with shiny skin and visible veins, respiratory distress, bilious aspirates/ vomiting, failure to pass meconium and features of peritonitis. Abdominal plain X- ray reveals the calcifications in the peritoneal cavity occasionally; the calcifications may extend to the scrotum. Calcifications are confirmed by ultrasound, appearing as hyper-echogenic images with posterior acoustic shadowing.

Three pathological types of meconium peritonitis can be distinguished depending on the degree of the inflammatory response: fibro-adhesive, cystic and generalized [5]. Fibro-adhesive meconium peritonitis is the most common and results from intense fibroblastic reaction; cyst type occurs when the perforation site is not completely closed and thus forms a thick-walled cyst. Generalized meconium peritonitis is characterized by diffuse bowel thickening of the affected segment, peritoneal fibrosis and calcium deposits. Meconium which is sterile causes chemical inflammation of the peritoneum due to antenatal or postnatal intestinal perforation. As the body attempts to seal off the source of inflammation, intra-peritoneal dystrophic calcification occurs and may extend as inguinal or scrotal masses. In most cases surgery is required immediately after birth. In rare cases, it heals spontaneously without any surgical intervention.

Management and surgical strategy of a patient with meconium peritonitis rely on the clinical presentation and the overall condition of the newborn. Surgery is necessary when signs of intestinal obstruction are present. The presence of intra-peritoneal calcifications is not an indication for surgery [6,7]. Early recognition and treatment of acid base imbalance, superimposed bacterial peritonitis, and septic shock can prevent mortality. The timing of delivery should therefore be discussed with pediatrician and pediatric surgeon. Surgery performed within 24 hours in newborns with bowel obstruction may also improve their outcome. Literature review suggests that the need for postnatal surgical intervention varies from 20-80%.

Diagnosis of meconium peritonitis is rare before 20 weeks’ because peristalsis rarely commences before this time. The first step in evaluation of the fetus with ascites and suspected meconium peritonitis is a careful survey of other aspects of fetal anatomy. If no other anomalies are identified, and the fetus is not hydropic, testing of maternal blood for antibodies to red cell determinants, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasmosis is indicated. Postnatal diagnosis of meconium peritonitis is established after correlation of the clinical presentation with abdominal and/or scrotum radiographs, ultrasound and CT scan [8]. It may be differentiated from liver calcifications that occur in infections with cytomegalovirus and parvovirus and intestinal intra-luminal calcifications which present in the multiple intestinal atresia, colonic atresia, or Hirschsprung's disease. A key element in the further management consists in excluding chromosomal malformations, congenital infections and cystic fibrosis [9].

Assessment of patients is done using a scoring system described by Zangheri. Score 0 describes the presence of isolated calcification, score 1A includes calcifications associated with ascites, score 1B includes calcifications associated with meconium pseudocyst, score 1C corresponds calcifications and dilated intestinal loops, score 2 is based upon the presence of calcifications and two of the events described above and score 3 includes all. The smallest probability for surgery corresponds to isolated cases of calcification (score 0). In other patients with score 1 to 3, the probability of surgery intervention increases to over 50% [10].

Infant in our case had abdominal distension with respiratory distress soon after birth without signs intestinal obstruction, radiographic studies showed meconium peritonitis. He was managed conservatively and feeds were established with an uneventful NICU stay. In some cases infants may need surgical intervention in view of intestinal obstruction. Mortality was reported in few cases due to complications of sepsis and hemorrhage.

Conclusion

We were cautious for any complications that might arise and were ready for any emergency surgical intervention if needed in case of any signs of intestinal obstruction. Baby was managed conservatively and needed no surgical intervention which has been rarely reported. The site of perforation in our case got sealed antenatally, indicating a self- limiting process which occurred postnatally.

Contributors: SAG: manuscript writing, manuscript editing, patient management; ST: critical inputs into the manuscript, patient management. SAG will act as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Sabetay C, Popescu I, Ciuce C. Tratat de chirurgie - volumul III - Chirurgie pediatrica. Editia a II-a. Editura Academiei Romane, 2013.

- Wax JR, Pinette MG. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of meconium periorchitis. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:415-417.

- Saleh N, Geipel A, Ulrich G, Heep A, Heydweiller A. Prenatal diagnosis and postnatal management of meconium peritonitis. J Perinat Med. 2009;37:535-538.

- Chan KL, Tang MH, Tse HY, Tang RY, Tam PK. Meconium peritonitis: prenatal diagnosis, postnatal management and outcome. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:676-682.

- W. S. Lorimer Jr., Ellis DG. Meconium peritonitis. Surgery. 1966;60:470-475

- Nam SH, Kim SC, Kim DY, Kim AR, Kim KS, Pi SY. Experience with meconium peritonitis. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2007;42:1822-1825.

- Maxfield C. Meconium Peritonitis. Oxford University Press. 2014;32:130-132.

- Garel C. Imagerie d'une péritonite méconiale à présentation clinique pseudotumorale. J Radiol. 1997;78:1288-1290.

- Casaccia G, Trucchi A, Nahom A, Aite L, Lucidi V, Giorlandino C, et al. The impact of cystic fibrosis on neonatal intestinal obstruction: the need for prenatal/neonatal screening. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:75-78.

- Zangheri G, Andreani M, Ciriello E, Urban G, Incerti M, Vergani P. Fetal intra-abdominal calcifications from meconium peritonitis: sonographic predictors of postnatal surgery. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:960-963.