6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff2432260000002708000001000100

6go6ckt5b5idvals|905

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Intercostal hernia is a rare clinical entity characterized by the protrusion of lung and/or abdominal viscera through a defect in an intercostal space. Intercostal hernias can be categorized by their contents (lung, liver, small and large bowel, gallbladder, omentum), or depending on their etiology. They generally develop after trauma or surgery. More rarely do they occur spontaneously or in the context of genetic syndromes. In recent years, a further categorization emerged, distinguishing hernias on the basis of the presence of a diaphragmatic defect. The term AAIH, “acquired abdominal intercostal hernia” is reserved to hernias whose intra-abdominal contents reach the intercostal space directly from the peritoneal cavity through an acquired defect in the abdominal wall. When lung or viscera reach the intercostal space through a diaphragmatic defect, the term TIH, “trans-diaphragmatic intercostal hernia”, is preferred. To this day, 22 AAIH cases and approximately 40 TIH cases have been described using the above definitions.

Case Report

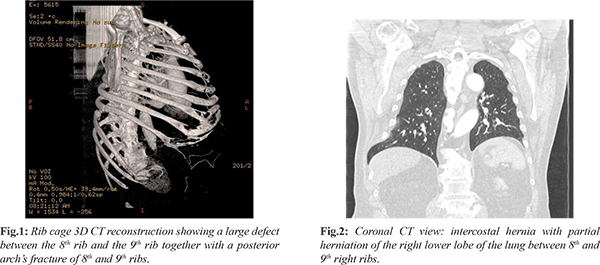

We report a rare case of inter-costal abdominal hernia in a patient who had already previously undergone trans-diaphragmatic inter-costal hernia surgery after a cough-induced fracture of the right costal margin associated with rib separation and subsequent abdominal visceral protrusion through intercostal space. This is a 73-year-old patient known for class II obesity, arterial hypertension, hypo-cholesterolemia and no previous thoraco-abdominal surgery, visiting his family physician for severe chest pain on the right side associated with dyspnea on exertion. These symptoms appeared after a severe cough episode that occurred in the context of bronchitis in the month of September 2014. Anamnesis reveals no history of direct trauma. Although clinical examination reveals a mass at the seventh rib, pain is treated conservatively at first. Three months later, due to persistence of symptoms, a thoraco-abdominal CT scan is requested. The CT allows the diagnosis of a partial herniation of the right lower lobe of the lung associated with a portion of the 7th segment of the liver through a dehiscence of intercostal muscles between the eighth and the ninth right ribs [Fig.1]. A fracture of the posterior arch of the eighth and ninth ribs is also reported [Fig.2]. Moreover, the CT allows the occasional diagnosis of ascending aortic aneurysm. The clinical examper formed at the time of admission to our surgical unit showed a mass in the right basi-thoracic region at the mid-axillary line, soft and painless to palpation, which enlarged with coughing and Valsalva maneuver and spontaneously reduced through a 4-finger diastasis between the eighth and the ninth ribs in the lateral left decubitus position. In the light of these findings, trans-diaphragmatic intercostal hernia (TIH) is diagnosed and surgery indication is decided.

Surgery is performed under general anesthesia with the patient in lateral left decubitus position. A 20-cm incision is made at the intercostal dehiscence and after sectioning the muscles, the eighth and ninth ribs are exposed. After opening and washing the pleural cavity, the diaphragmatic defect is sutured and the two ribs in question are approximated with periosteal sutures using Orthocord®. The muscular wall is mended with a 1-0 Vicryl® continuous suture. Two drains are placed in pre and retro muscular position. Post-operative chest radiography confirms the absence of pneumothorax. The post-operative period is uneventful, drains are removed on the third and sixth days after surgery, and the patient is discharged after a week. At the follow-up check one month after surgery the patient did not show symptoms and the clinical examination was normal.

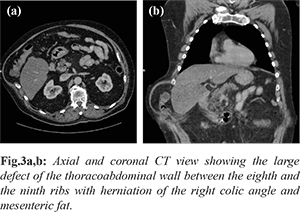

Some months later, after a violent cough episode, the patient notices the appearance of a gradually progressive mass in the right basi-thoracic region. On clinical examination, a 15x10 cm mass is described at the eighth intercostal space, located more anteriorly compared to the previous one, soft and painless to palpation and spontaneously reducing in the lateral left decubitus position. Peristaltic sounds are heard on auscultation. A thoraco-abdominal CT scan shows a large defect of the thoraco-abdominal wall between the eighth and the ninth ribs with herniation of the right colic angle and mesenteric fat [Fig.3a,b]. Surgery is performed under general anesthesia with the patient in lateral left decubitus position. An incision is made at the anterior part of the previous scar. Torn Orthocord® wires are found on the costal plane. After being exposed, the hernial sac is opened, partly resected and finally mended with 2-0 Vicryl® continuous suture. The two ribs are approximated with interrupted stitches using Orthocord®. After preparing the space between the costal plane and the muscles, a polyester mesh is applied in pre-muscular position, and is then secured by 1-0 Vicryl® stitches. Two drains are placed, one in the pre-muscular plane and one in the subcutaneous tissue. Post-operative recovery is uneventful; on the fifth day after surgery the drains are removed and the patient is discharged. At the 3-month follow-up there was no sign of recurrence.

Discussion

Intercostal hernia is a rare condition, scarcely reported in the literature, with almost exclusively occasional case reports being available. However, given that such conditions are often asymptomatic, their real prevalence is likely under-estimated. A recent review by Erdas et al. showed that AIHs are more frequent among males (male/female ratio 1.8/1) and that the mean age at the time of diagnosis is 58.4 years [

1]. Most intercostal hernias are caused by penetrating or blunt injury to the thoraco-abdominal wall, but they can also develop after violent attacks of coughing or even spontaneously, often in the context of genetic syndromes (e.g. Marfan, Ehlers-Danlos). Nevertheless, in almost one fifth of the cases no cause is identified and the hernia is considered spontaneous [

2].

Potential risk factors that are often implied in the development of hernia are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

2], smoking, obesity, osteoporosis, advanced age and collagen diseases. Inter-costal hernias have a tendency to develop more frequently on the left side of the chest and under the 7th rib. From an anatomical perspective, certain areas are more prone to develop intercostal hernia. The chest wall is indeed weaker anteriorly, from the costo-chondral junction to the sternum, due to the lack of external intercostal muscles, and posteriorly, between the posterior costal angle and the vertebra, due to the lack of internal intercostal muscles. Hernial content may consist of colon, omentum, liver, lung, small intestine, stomach and spleen. Clinically, a patient with intercostal hernia presents with a palpable, soft, reducible mass in the infero-lateral portion of the chest, worsened by exertion and coughing. Patients generally report discomfort or pain, but they can also be asymptomatic, as two years pass, on average, between trauma and hospitalization [

1]. The intercostal hernias may be confused with lipomas or hematomas [

3]. High diagnostic suspicion, precise anamnesis and accurate clinical examination are therefore important in presence of chest swelling after minor or major trauma.

CT scan is the most used diagnostic tool, since it allows to confirm intercostal hernia, rule out visceral lesions and plan surgery [

4]. Ultrasonography can be useful to carry out a first assessment, since it is faster and less expensive but not as effective as CT scan in identifying associated intra-abdominal lesions [

5-

9]. As reported by Erdas et al. 15% of AAIHs can be complicated by incarceration or strangulation [

1]. For this reason, the recommended treatment for intercostal hernia is always surgery, but a conservative approach may be indicated for elderly patients with severe co-morbidities which pose a high surgical risk. Although intercostal defects are most often repaired through thoracotomy, indirect approaches (laparotomy and laparoscopy) may be more indicated in case where an associated diaphragmatic or visceral lesion is suspected [

10]. There are no specific recommendations as to the best repair technique; however, according to the principles of modern hernia surgery, tension-free repair with prosthetic mesh should be preferred. Moreover, rib approximation may be indicated, but since it may cause discomfort and chronic pain [

11], rib suture should be reserved to the cases where the intercostal defect is particularly significant.

In the case we described, recurrence was diagnosed approximately seven months after the first surgery. It could be rightfully argued that no mesh was used during the first surgery, but the available data show that in any case the recurrence rate remains high (28.6%) regardless of the technique used [

1].

Conclusion

However rare, intercostal hernias, both abdominal and trans-diaphragmatic, must be suspected when patients present with palpable chest swelling after thoraco-abdominal trauma. CT is the elective technique to perform diagnosis and identify the presence of co-existing diaphragmatic defects or intra-abdominal lesions. The treatment of choice is surgery (thoracotomy, laparotomy or laparoscopy), possibly using tension-free mesh repair. The recurrence rate is high, which ever technique is chosen.

Contributors: RMC: manuscript writing, patient management; GMD: manuscript editing; JCR: manuscript editing, patient management. RMC will act as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Erdas E. Licheri S, Calò PG, Pomata M. Acquired abdominal intercostal hernia: case report and systematic review of the literature. Hernia. 2014;18:607-615.

- Ampollini L, Cattelani L, Carbognani P, Rusca M. Spontaneous abdominal – intercostal hernia”, Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:275.

- Biswas S, Keddington J. Soft right chest wall swellings imulating lipoma following motor vehicle accident: transdiaphragmatic intercostal hernia. A case report and review of literature.” Hernia. 2008;12(5):539-543.

- Unlu E, Temizoz O, Cagli B. Acquired spontaneous intercostal abdominal hernia: case report and a comprehensivereview of the world literature. Australas Radiol. 2007;51:163-167.

- Rosch R, Junge K, Conze J, Krones CJ, Klinge U, Schumpelick V. Incisional intercostal hernia after a nephrectomy. Hernia. 2006;10: 97-99.

- Bendinelli C, Martin A, Nebauer SD, Balogh ZJ. Strangulated intercostal liver herniation subsequent to blunt trauma. First report with review of the world literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7:23.

- Gundara JS, Ip JC, Lee JC. Unusually complicated chest infection: colon containing intercostal hernia. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:851-852.

- Ryan G, Cavallucci D. Traumatic abdominal intercostal hernia without diaphragmatic injury. Trauma. 2011;13:364-367.

- Rodriguez Couso JL, Ladra MJ, Paulos Gomez AM, Fernandez Perez JA, Garcia Prim JM. Hernie digestive intercostale post-traumatique. J Chir. 2009;146:189-190.

- Gundara JS, Ip JC, Lee JC. Unusually complicated chest infection: colon containing intercostal hernia. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:851-852.

- Visagan R, McCormack DJ, Shipolini AR, Jarral OA. Are intercostal sutures better than pericostal sutures for closing a thoracotomy? Interact Cardio Vasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:807-815.