Banu Cevik1, Arzum Orskiran1, Ayhan Cevik2

From the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care1 & Surgery2,

Dr. Lutfi Kirdar Kartal Education and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Banu Cevik

Email: banueler@yahoo.com

Abstract

Adrenal incidentaloma can be described as adrenal lesions that are incidentally diagnosed during abdominal surgery or any abdominal screening without any clinical findings. Roughly 30% of them are functional and a small group of 5-7% may exist as pheochromocytoma. Anaesthetic drugs can exacerbate the cardiovascular effects of catecholamines secreted by these tumours and peroperative management may become complicated. Despite the new developments of drugs and techniques, the management of patients with pheochromocytoma is still an anaesthesiologist’s nightmare. We describe a case of pheochromocytoma in a 58-year-old woman, found coincidentally during surgery. This case serves as an example, when presented with similar findings, to consider pheochromocytoma as one of the differential diagnoses.

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff745c010000003c00000001000e00 6go6ckt5b5idvals|132 6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Pheochromocytoma is a tumour that weighs 1 to 4,000 grams and secrets catecholamine originating in the cromaffin cells of adrenal medulla. The incidence is about 1-4/1,000,000 per year and most tumours occur between ages 20 and 50 years. A high proportion of these tumours are silent but at times hypertensive crises may be triggered on inducing with anaesthetic drugs. In this condition, the mortality rates can rise up to 80% [1]. We describe a patient having undiagnosed pheochromocytoma developing hypertensive crisis during surgery and emphasize the importance of this unexpected condition following anaesthesia induction.

Case Report

A previously healthy 58 year old female patient presenting with epigastric pain and nausea for 1 month was admitted to hospital. During abdominal ultrasonography, a mass containing both liquid and solid areas was detected on the liver. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a 60 x 55 mm size mass with regular borders and showing heterogeneous contrast uptake. In the routine laboratory tests, no data was suggestive to suspect any other pathology. The patient was accepted to the operating room for explorative laparotomy and excision of the mass. After standard monitoring including ECG, non-invasive blood pressure and pulse oximetry, induction of anaesthesia was done with 6 mg/kg thiopental sodium, 75 µg fentanyl and 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium. Sevoflurane 1% in 50%O2-N2O mixture was used for the maintenance of anaesthesia. During surgery, after 10 minutes from induction, the arterial blood pressure abruptly increased up to 210/120 mmHg and the heart rate increased to 150 beats/min. Additional to standard monitoring, an arterial catheter was inserted to be detect and treat arterial blood pressure changes. To return hemodynamic values to normal, fentanyl 100 µg, nitroprusside 160 µg were given intravenously and anaesthesia depth was increased by raising the minimum alveolar concentration of sevoflurane but arterial blood pressure continued to rise to 220/130 mmHg. Esmolol was titrated to 300 µg/kg/min and nitroprusside to 2 µg/kg/min. The treatment resulted in arterial blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg and heart rate of 110 beats/min. Sustained elevation of blood pressure and persistent tachycardia made us suspect pheochromocytoma. Surgery was continued after control of arterial blood pressure, and during exploration of abdomen a solid mass on the right adrenal gland was detected. The patient underwent right adrenelectomy in view of suspected asymptomatic adrenal lesion. Blood pressure was labile during handling and excision of tumour so the doses of nitroprusside and esmolol were adjusted. The cystic lesion on the liver was also completely excised. The patient was transferred to Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for further monitoring and soft extubation. She was extubated after 4 hours and followed in the ICU until her blood pressures were within normal limits for 24 hours. She was discharged to clinic on the 2nd day and home on the 7th day of hospital admission. Histopathology data correlated with pheochromocytoma. .

Discussion

The intraoperative incidental presentation of pheochromocytoma represents therapeutic challenge as a consequence of significant complications directly related to increase in systolic blood pressure. The incidental pheochromocytoma smaller than 1 cm are generally asymptomatic [2]. Rarely, some large pheochromocytomas do not show any clinical symptoms [3]. Invasive procedures such as venous catheterization, tracheal intubation, skin incision, anaesthetic drugs and palpitation of tumour will precipitate the hypertensive crisis. Anaesthetic drugs triggered the hypertensive crisis in our case in view of crises occurring immediately after the induction of anaesthesia.

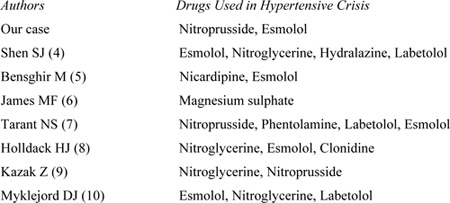

Table 1 mentions the different drugs used by various authors for control of hypertensive crises. Alpha and beta adrenergic blockers should be considered in hypertensive crisis. In our case sodium nitroprusside and esmolol were used. Sodium nitroprusside is considered to be most effective parenteral drug for the treatment of most hypertensive emergencies as it is an effective arterial and venous vasodilator. It has an extremely rapid onset (within seconds) and duration of action of 1-2 minutes with a plasma half-life of 3-4 minutes. It is light sensitive, requires intra-arterial monitoring and has risk of developing fatal cyanide or thiocyanate toxicity. Nitroprusside releases cyanide which is metabolized in liver and is excreted largely by the kidney. Therefore, cyanide removal requires the adequate liver and renal function. Coma, encephalopathy, convulsions, unexplained cardiac arrest, and irreversible neurologic abnormalities have been documented as a result of cyanide toxicity. The current methods of monitoring for cyanide toxicity are insensitive and not widely available and the clinical manifestations of cyanide toxicity like coma, encephalopathy, cardiac arrest often present too late for effective treatment to be initiated [4].

Esmolol is a cardioselective, beta blocking agent with immediate onset of action, a short half-life of 9 minutes, and duration of action of 10–30 minutes. Its short half-life is due to rapid hydrolysis by red blood cell esterases and is not dependent on renal or hepatic function for metabolism. These properties make esmolol an ideal agent for use in critically ill patients with hypertensive emergency. For hypertensive emergencies, esmolol often must be combined with a vasodilating agent to achieve optimal blood pressure control [4].

Table-1: Drugs used in different studies to control hypertensive crisis

Our patient had absence of typical symptoms of pheochromocytoma, consisting of hypertension, headaches, palpitations, and sweating attacks. The patient having normotension despite high circulating levels of catecholamines can be explained by hypovolemia and nonresponsiveness due to prolonged stimulation [4]. Continuation with the planned surgery is controversial in such cases. In our case, the use of sodium nitroprusside and esmolol together with the intravascular hydration effectively controlled the crisis preventing the cancellation of surgery.

In conclusion, rare tumour like pheochromocytoma, may present unexpectedly during anaesthesia. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are the keys to reduce morbidity and mortality. In any patient presenting with unexplained hypertension and tachycardia during anaesthesia, undiagnosed pheochromocytoma must be considered.

References

Our patient had absence of typical symptoms of pheochromocytoma, consisting of hypertension, headaches, palpitations, and sweating attacks. The patient having normotension despite high circulating levels of catecholamines can be explained by hypovolemia and nonresponsiveness due to prolonged stimulation [4]. Continuation with the planned surgery is controversial in such cases. In our case, the use of sodium nitroprusside and esmolol together with the intravascular hydration effectively controlled the crisis preventing the cancellation of surgery.

In conclusion, rare tumour like pheochromocytoma, may present unexpectedly during anaesthesia. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are the keys to reduce morbidity and mortality. In any patient presenting with unexplained hypertension and tachycardia during anaesthesia, undiagnosed pheochromocytoma must be considered.

References

- O’Riordan JA. Pheochromocytomas and anesthesia.Int Anesthesiol Clin 1997; 35, 99-127.

- Blake MA, Krishnamoorthy SA, Boland GW, Sweeney AT, Pitman MB, Harisinghani M et al. Low-density pheochromocytoma on CT: A mimicker of adrenal adenoma. Am J Roentgenol 2003; 181:1663-1668.

- Shin S, Tsujihata M, Miyake O, Itoh H, Itatani H. Asymptomatic pheochromocytoma: a report of three cases. Hinyokika Kiyo 1994; 40: 1087-1091.

- Shen SJ, Cheng HM, Chiu AW, Chou CW, Chen JY. Perioperative hypertensive crisis in clinically silent pheochromocytomas: report of four cases. Chang Gung Med J 2005; 28: 44-50.

- Bensghir M, Elwali A, Lalaoui SJ, Kamili ND, Alaoui H, Laoutid J et al. Management of undiagnosed pheochromocytoma with acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surgery 2009; 4:, 35.

- James MF. Use of magnesium sulphate in the anaesthetic management of pheochromocytoma: a review of 17 anaesthetics. Br J Anaesth 1989; 62: 616-623.

- Tarant NS, Dacanay RG, Mecklenburg BW, Birmingham SD, Lujan E, Green G. Acute appendicitis in a patient with undiagnosed pheochromocytoma. Anesth Analg 2006; 102: 642-643.

- Holldack HJ. Induction of anesthesia triggers hypertensive crisis in a patient with undiagnosed pheochromocytoma: could rocuronium be to blame? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2007; 21: 858-862.

- Kazak Z, Darcin K, Kazbek K, Sekerci S, Süer H. Hypertensive crisis in a patient with an undiagnosed pheocromocytoma. Erciyes Medical Journal 2010; 32: 213-216.

- Myklejord DJ. Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma: The anesthesiologist nightmare. Clin Med Res 2004; 2: 59-62.

|