Govind Eriat, Radheshyam Naik, BJ Srinivas, S Smitha, Mehdi Intezar, Raghuram CP, S Gunasagar, Shilpa Prabhudesai, Diganta Hazarika, Renu Ethirajan

From the Department of Stem Cells and Bone Marrow Transplant, HCG, Bangalore, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Govind Eriat

Email: research.hcg@gmail.com

Abstract

Myelophthisis is the breakdown of bone marrow due to replacement of hematopoietic tissue by anomalous tissue, mostly seen in metastatic carcinomas. Metastasis of colon cancer to the bone marrow is seldom seen. We present a very unique case of adenocarcinoma of the colon, with myelophthisis; where the patient presented with a leukemic blood picture and bleeding due to coagulopathy, masquerading as an acute leukemia without any primary bowel symptoms.

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff04c201000000b200000001000400 6go6ckt5b5idvals|146 6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext An established treatment for colon cancer is surgical resection of tumor before metastasis or invasion into the bowel wall [1]. Bone marrow metastasis in colon cancer has been examined in extensive necropsy studies and found to be 16 to 34% [2]. However, in clinical practice, suppressed secondary infiltration to bone marrow is not usually seen. We present a case of adenocarcinoma of the colon, with myelophthisis; where the patient was diagnosed as acute leukemia. This case is unique as metastases to the bone marrow has shown clinical features and hematological picture suggesting acute leukemia.

Case Report

Mr. X aged 75 without any severe co morbidities developed high grade fever and fatigue, three months ago. He was evaluated elsewhere and treated empirically as malaria. Patient became afebrile, however he developed progressive fatigability with new onset gingival bleeds, hematochezia and extensive petechiae. He had no history of weight loss, altered bowel symptoms, dysphagia, abdominal distension or melena. He was diagnosed with acute leukemia upon bone marrow aspiration from a sternal puncture. Patient was then referred to our Oncospeciality hospital for further management. Upon admission patient was, icteric, pale without significant lymphadenopathy or edema with a performance status of 2 (ECOG). Gingival bleeds, bilateral upper and lower limb ecchymosis were accompanied by ongoing epistaxis. Fundoscopy was normal. Examination of the abdomen revealed hepatosplenomegaly and a 2x3 cm non tender swelling in the right hypochondriac region 6 cm below the lower border of the liver. Rectal examinations were noncontributory. Waldeyers’s ring and testes were not involved.

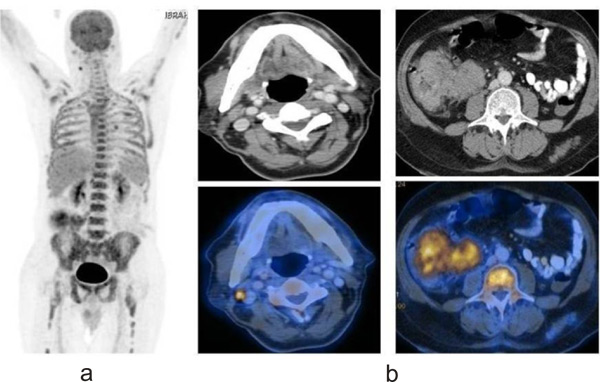

Work up showed high uncorrected reticulocyte index with a hypochromic blood picture with anisopoikilocytosis and 30% atypical blasts, indirect hyperbilirubinemia, high LDH, and normal haptoglobulin. In view of a palpable mass in right hypochondrium, a sonological examination of the abdomen was warranted, which revealed that in addition to hepatosplenomegaly there was a diffuse irregular mass involving the proximal ascending colon. An FDG -PET [Fig. 1] based staging work up revealed a large ill-defined irregular mass measuring 11.6x9.2 cm in the lower abdomen in the medial wall of proximal ascending colon without ascites, with cutaneous deposits in the right breast and gluteal region.

1a: A discrete enhancing right submandibular lymphnode of 7mm

1a: A discrete enhancing right submandibular lymphnode of 7mm

1b: Well defined polypoidal moderate enhancing 2.9 x 3.1 cm mass in the 1st part of duodenum region along the medial wall without any adjacent extra-luminal extension. Large ill defined irregular heterogeneously enhancing mass measuring 11.6 x 9.2cm in the right lower abdomen in relation to the medial wall of proximal ascending colon, caecum and ileo-caecal junction

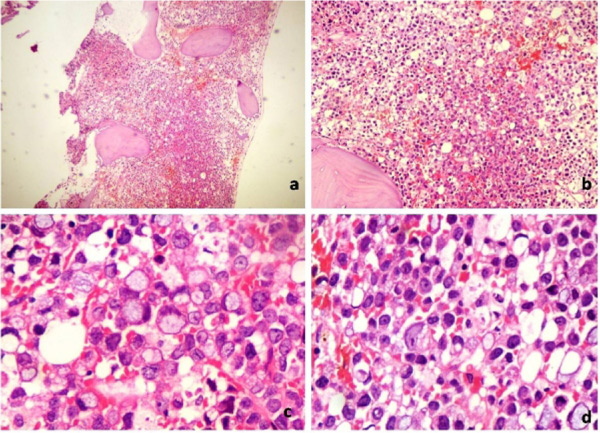

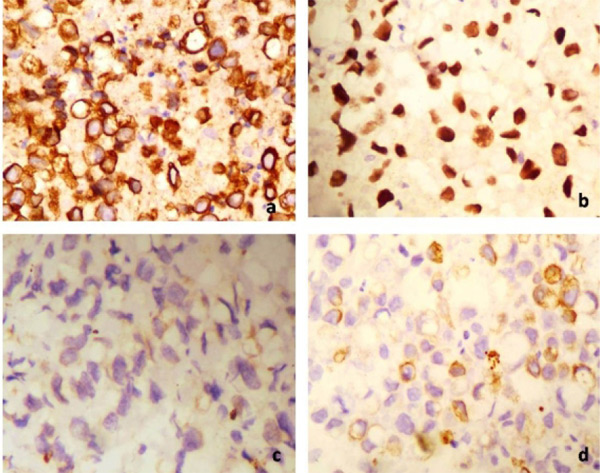

Bone marrow aspirate showed atypical blast with cytoplasmic budding with coarse granules which were MPO and PAS negative , but trephine biopsy revealed complete effacement of the bone marrow with signet ring cells from an adenocarcinoma which were positive for pancytokeratin, CDX2, CK20 and very focally for CK7 [Fig. 2,3] CEA levels were elevated at 44.4ng/ml. Patients’ coagulopathy was managed with fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate, and received multiple PRC transfusions for ongoing gastrointestinal bleed. After hemodynamic stabilization colonoscopy was attempted. However, biopsy failed due to torrential hemorrhage from the mass. There were no intraluminal lesions on the gastroduodenoscopy. Patient was planned for embolization mass for immediate haemostasis, followed by FOLFOX based chemotherapy with biologicals. However, post chemo embolization the patient developed a massive bleed from the puncture site and could not be revived despite aggressive resuscitation in the medical intensive care unit.

Fig. 2: Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma. heatoxyline-Easin stain Low power 4X (a) medium 10X (b) and high power 40 X (c&d); note the signet rings.

Fig. 3: Tumour cells are positive for pancytokeratin (a), CSX 2(b), very focally for CK 7 (c) and positive for CK 20 (d)

Discussion

Colon cancer remains one of world leading cause of tumor-related deaths, in spite of screening for fecal occult blood and colonoscopy, use of “no-touch” surgery, triumphant adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and life-prolonging palliative therapy [3]. Micrometastatic spread of visible cancer cells could be one of the leading cause of deaths in patients with colon cancer [4]. The occurrence of micrometastases is a superior prognostic factor in colorectal cancer [5,6], thus identifying patients at risk for relapse. Due to the easy access, generally bone marrow is the preferred organ of choice for taking samples to detect micrometastases. Autopsy studies have exposed that even though bone metastases are infrequent in stage IV colorectal cancer, micrometastasis can be detected quite regularly [7].

Bone marrow derived cells (BMDC) have shown to participate in the growth and spread of tumors of the breast, lung, brain and stomach. Some studies show that cancer cells fuses with macrophages or other BMDC [8]. There are very few studies to show the involvement of bone marrow in colon cancers; however these findings are of prime importance to bring a paradigm shift in colon cancer therapy. A small sub-group of tumour-initiating cells (TICs) are found in the colon, which is believed to be a functionally consistent stem-cell-like population driving tumour continuance and metastasis pattern [9].

Emerging data indicate that reliable and specific anti-cytokeratin antibodies like A45-B/B3 can be used as markers for the recognition of micrometastatic tumour cells in bone marrow. Prospective clinical studies have revealed that immunoassays based on anti-cytokeratine antibodies recognize patients' subgroups with early onset of metastasis and reduced overall survival in various epithelial tumour bodies, including breast, colon, rectum, stomach, oesophagus, prostate, renal, bladder, and non-small cell lung cancer [10]. Apart from this, assessing tumour specific antigens and other glycoproteins associated with the primary tumour in distant sites help identify early signs of relapse in such cases.

Use of the alkaline phosphatase–antialkaline phosphatase reaction based immunocytology polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques, ?ow cytometry, and ?uorescent in situ hybridization (FITC) are some of the methods to detect distant organ micrometastases [3]. The requirement for small cell yield and good reliability and validity make magnetic activated cell sorter superior to earlier techniques. Small amount of cells can be amplified and micrometastases detected using MACS [11].

In this case, the patient had no primary symptoms suggestive of a colonic malignancy, which is quite unusual for such an extensive disease. And it is a palpable mass per abdomen upon clinical examination which directed further evaluation and confirmed the diagnosis of myelophthisis by carcinoma colon. In this era of protocol based testing and high end radiological investigations, the benefits of a detailed history and thorough clinical examination cannot be overstated.

Various new drugs and protocols are tested every year. Assessing micrometastatic disease will allow us to recognize the early cancer and the mechanisms behind relapses [3]. We could adapt these techniques in our lab to detect the micrometastasis of solid tumors and revamp the existing staging system and subsequent therapeutic interventions. Proven micrometastasis, in an otherwise documented stage one disease would upstage the disease and question our existing treatment strategies.

References

- Yilmaz Sema, Özütemiz Ömer, Alkanat Murat. Colon cancer with bone marrow metastasis concurrent with disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome: Case report. The Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology.2001;12:162-164.

- Bresalier RS, Young KS. Malignant neoplasms of the large intestine. In: Feldman M, Sleisenger MH, Scharschimidt BF., (eds), Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Co.1998; 906-942.

- Weihrauch MR, Skibowski E, Koslowsky TC, Voiss W, Re D, Kuhn-Regnier F, et al. Immunomagnetic enrichment and detection of micrometastases in colorectal cancer: correlation with established clinical parameters. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3404-3412.

- Braun S, Pantel K. Micrometastatic bone marrow involvement: detection and prognostic significance. Med Oncol. 1999;16:154-165.

- Lindeman F, Schlimok G, Dirschedl P, Witte J, Riethmuller G. Prognostic significance of micrometastatic tumour cells in bone marrow of colorectal cancer patients. Lancet 1992; 340:685-689.

- Leinung S, Wurl P, Weiss CL, Roder I, Schonfelder M. Cytokeratin-positive cells in bone marrow in comparison with other prognostic factors in colon carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2000; 385:337-343.

- Grunow N, Goertchen R. Micrometastases of the spine in an unselected autopsy sample with nearly 100% autopsy frequency (Gorlitz study)[in German]. Pathologe 1991; 12:270-274.

- Pawelek JM, Chakraborty AK. The cancer cell – leukocyte fusion theory of metastasis. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;101:397-444.

- Dieter SM, Ball CR, Hoffmann CM, Nowrouzi A, Herbst F, Zavidij O, et al. Distinct types of tumor-initiating cells from human colon cancer tumors and metastases. Cell Stem Cell 2011;9:357-365.

- Braun S, Schindlbeck C, Hepp F, Janni W, Kentenich C, Riethmüller G, Pantel K. Occult tumor cells in bone marrow of patients with locoregionally restricted ovarian cancer predict early distant metastatic relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:368-375.

- Miltenyi S, Muller W, Weichel W, Radbruch A. High gradient magnetic cell separation with MACS. Cytometry 1990;11:231-238.

|