6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff6409320000006807000001000600

6go6ckt5b5idvals|2052

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Amyand's hernia occurs in 1% of inguinal hernias, in which a normal vermiform appendix is incarcerated within the hernia, whilst associated appendicitis occurs 0.1% of cases [

1-

3]. It is most commonly found in males, on the right, and can occur in any age. Amyand’s hernia was first reported case in year 1736 (perforated appendicitis), but its pathophysiology and risk factors remain unclear [

4]. It is believed to be secondary to a patent processus vaginalis or the presence of a fibrous band between the testes and hernia. Amyand’s hernia usually presents as an incarcerated inguinal hernia, but its presentation can be quite variable. Inguinal hernias are typically diagnosed clinically or with ultrasound. Computed tomography scan (CT) is the most commonly used imaging modality for evaluation of complex abdominal hernias.

Appendicitis arises from luminal obstruction (i.e. appendocolith), causing bacterial overgrowth, increased pressure and localized ischaemia, resulting in appendicitis, gangrenous perforation, thus leading to localized abscess or peritonitis. Appendicitis can also occur as a result of strangulation of the appendix within the Amyand’s hernia. Appendicitis present with right iliac pain, vomiting, fever, loss of appetite and raised inflammatory markers [(white cell count (WCC), C-reactive protein (CRP)]. Appendicectomy is the treatment of choice and this is increasingly done as a laparoscopic procedure [

5].

The aim of the study is to illustrate two cases where patients experienced appendicitis within an Amyand’s hernia. These two cases illustrate the management of appendicitis prior to repair of the Amyand’s hernia.

Case Reports

Case 1

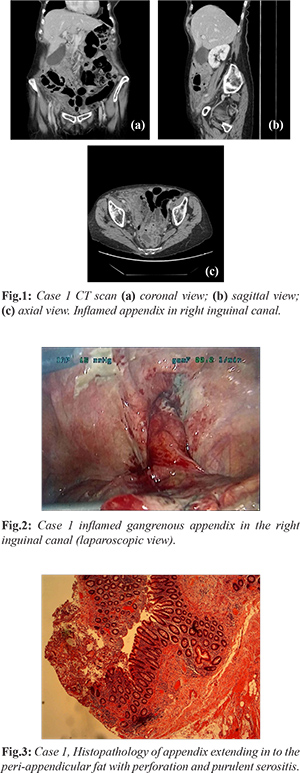

A 83 years old female with past history of right inguinal hernia, abdominal hysterectomy, hypercholesterolemia, primary hyperparathyroidism, hypertension, hypercalcemia and osteopenia, presented to the A & E (accident and emergency) department with acute right groin pain, abdominal distension and rigors for 3 days. She was having tender right iliac fossa and right inguinal hernial canal. She had a temperature (38°C), tachycardia (heart rate 113 beat per minute) with pain score 8/10 (Numerical Pain Rating Scale), CRP 120 mg/L and white cell count 10.6×109/L. Arterial blood gases (ABG) demonstrated respiratory alkalosis on room air (pH 7.47, pCO2 4.2 kPa, HCO3 23.3 mmol/L) and lactate of 2 mmol/L. She was commenced on intravenous fluids and kept nil per mouth, and catheterized.Inpatient CT scan demonstrated acute appendicitis herniating into the inguinal hernia [Fig.1]. She was commenced on intravenous antibiotics. She subsequently underwent laparoscopic appendectomy on the NCEPOD (national confidential enquiry into patient outcomes & deaths) list, where an acutely inflamed gangrenous appendix was found within the right inguinal hernia [Fig.2]. Post-operative recovery was generally uneventful and patient was discharged with oral antibiotics for 5 days. Histopathology demonstrated transmural neutrophilic inflammation of the appendix extending in to the peri-appendicular fat with perforation and purulent serositis [Fig.3]. Patient subsequently underwent laparoscopic totally extra-peritoneal hernia (TEP) repair 6 months later.

Case 2

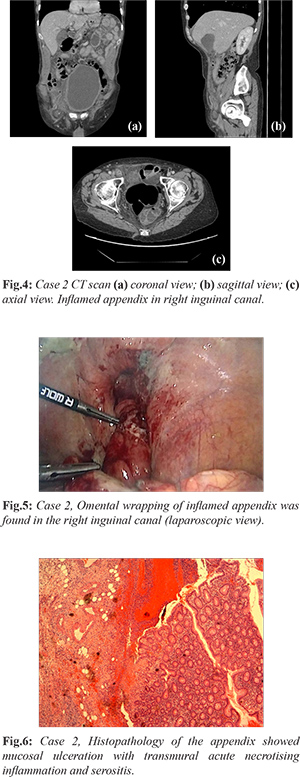

60 years old male with benign hypertrophy of prostate and glaucoma presented in A&E with acute abdominal pain (central abdominal with migration to right inguinal fossa) for 1 day. Clinically he had a painful right groin swelling with onset of abdominal pain, without fever. He had generalised abdominal tenderness which centralised over the Mcburney's point. On his right inguinal area there was 2×4 cm swelling, no cough impulse, pulsation, tenderness or erythema. Bowel sounds were heard. Serological tests showed raised inflammatory markers (WCC 13.9×109, CRP 77 mg/L). A subsequent CT scan demonstrated acute appendicitis in a right inguinal hernia (Amyand’s hernia) [Fig.4]. He was commenced on intravenous antibiotics. He underwent laparoscopic appendectomy on the NCEPOD list. Omental wrapping of inflamed appendix was found in the right inguinal canal [Fig.5]. The tip was adhered to the hernia sac and had to be freed by blunt dissection associated with reducing the hernia with external pressure. The appendix was dissected out of the hernia successfully via blunt dissection and some hydro-dissection with external pressure on the hernia. Post-operative period was uneventful and patient was subsequently discharged with oral antibiotics with review in out-patient clinic for elective laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Histopathology of the appendix showed mucosal ulceration with transmural acute necrotising inflammation and serositis [Fig.6].

Discussion

Amyand’s hernia is most frequently reported in men, on the right side, exceptions occur in situs inversus, intestinal mal-rotation, a very mobile caecum or a large appendix [

6]. Amyand’s hernia may contain cecum, bladder, ovary, fallopian tube, omentum or a Meckel’s diverticulum. Amyand’s hernia usually presents as strangulated or incarcerated hernia with coincidental finding of appendix in the hernia. Appendicitis can result from either obstruction or direct trauma over the hernia, resulting in a reduced vascular flow, ischemia and infection.

Pre-operative clinical diagnosis is difficult, but can be aided by trans-abdominal ultrasound or computed tomography CT scan [

7-

9]. Diagnostic laparoscopy can also demonstrate a Amyand hernia with a tubular blind-ended structure originating from the cecum wall and extending to the hernia sac. There is no standardized treatment for Amyand’s hernias. Losanoff and Basson proposed an Amyand hernia classification system in 2007 with guidelines for surgical management (

Table 1) [

10,

11]. Management should be individualized according to each case in respect to patient co-morbidities.

Conclusion

These two cases demonstrated Amyand’s hernia, presenting with typical features of appendicitis. At diagnostic laparoscopy, the inflamed appendix was found in the inguinal canal.These two patients underwent laparoscopic appendicectomy, but didn’t have their hernias repaired at the time of the operation as there was too much inflammation.

Contributors: FF: Manuscript writing, patient management; OS, MAG: manuscript revision and patient management; MMS, UAK: critical inputs into the manuscript and patient management. MAG will act as study guarantor. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of the study.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Baldassarre E, Centonze A, Mazzei A, Rubino R. Amyand's hernia in premature twins. Hernia. 2009;13(2):229-230.

- Sharma H, Gupta A, Shekhawat N, Memon B, Memon M. Amyand's hernia: a report of 18 consecutive patients over a 15-year period. Hernia. 2007;11(1):31-35.

- Burgess P, Brockmeyer J, Johnson E. Amyand hernia repaired with Bio-A: a case report and review. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(1):62-66.

- Amyand C. Of an inguinal rupture, with a pin in the appendix coeci, incrusted with stone; and some observations on wounds in the guts. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1735;39(8):329-342.

- Jaschinski T, Mosch C, Eikermann M, Neugebauer E, Sauerland S. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11(11): CD001546.

- Unver M, Ozturk S, Karaman K, Turgut E. Left sided Amyand's hernia. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5(10):285-286.

- Maekawa T. Amyand's hernia diagnosed by computed tomography. Intern Med. 2017;56(19):2679-2680.

- Guler I, Alkan E, Nayman A, Tolu I. Amyand's hernia: Ultrasonography findings. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(1):e15-17.

- Constantine S. Computed tomography appearances of Amyand hernia. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33(3):359-362.

- Losanoff J, Basson M. Amyand hernia: what lies beneath-a proposed classification scheme to determine management. Am Surg. 2007;73(12):1288-1290.

- Losanoff J, Basson M. Amyand hernia: a classification to improve management. Hernia. 2008;12(3):325-326.