6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff34ae03000000fc01000001000d00

6go6ckt5b5idvals|226

6go6ckt5b5idcol1|ID

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Facial diplegia is an extremely rare [

1] condition which occurs with various systemic illnesses such as sarcoidosis, Lyme disease and Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS), to name a few. It often occurs as a simultaneous onset, which means the involvement of the opposite side occurs about 30 days of the onset of the first side. It most often occurs as a special finding of a symptom complex in systemic diseases. It occurs in about 0.3% to 2.0% of facial palsy cases [

2]. A study of Adour et al, found only three bilateral cases in a consecutive series of 1,000 patients with Bell’s palsy [

3].

The relative lack of awareness of this condition often leads to dilemma in diagnosis. In this case study, we report a 22-year old female who developed an isolated, spontaneous, simultaneous facial diplegia which was misdiagnosed as bilateral Bell’s palsy.

Case Report

A 22-year female developed a sudden onset of left sided facial paralysis. Her major complaints were left ear pain followed by deviation of mouth, partial loss of taste and difficulty in closing left eye. She also had associated shortness in breath and palpitations. She consulted a neuro physician and was diagnosed as left sided Bell’s palsy. She was advised physiotherapy which resulted in gradual improvement in facial muscle strength with electrical stimulation and facial exercise over the period of one month.

Thirty days after presentation, she experienced gradual onset slight weakness on right side of her face and also found difficulty in opening her jaw. Within next three days, she developed complete facial weakness on her right side along with complete lose of taste. A second consultation lead to suspicion of a space occupying lesion and she was advised to go for computerized tomography (CT) of the brain, to ascertain the presence or absence of the lesion. The result of the study was negative ruling out any space occupying lesions. Without any further evaluation or investigation, she was diagnosed as having bilateral Bell’s palsy.

She complained about severe facial asymmetry, difficulty in mashing food and make facial expressions, as the weakness was now bilateral. She continued physiotherapy and following up with the neuro physician. Her recovery from the impairment was slow and she isolated herself due to her severe facial asymmetry. She visited our outreach physiotherapy centre for further management. It was 64 days after her first episode. During a detailed neuro physiotherapy evaluation, they found involvement of various cranial nerves and some variations in her deep tendon reflexes. On suspicion of it being a variant of GBS, they referred to us for another opinion in order to confirm their suspicion. While exploring the history, she hinted that she suffered from upper respiratory infection just before the first episode.

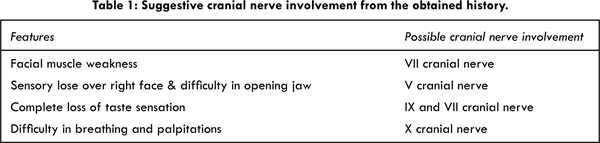

On examination, there was bilateral facial weakness (right more pronounced than left), severe facial asymmetry, lose of nasolabial fold, inability in closing right eye, unable to purse lip or smile. Bell’s phenomenon was positive on her right side. Cranial nerve examination showed involvement of trigeminal nerve (loss of sensation over right side face); facial nerve (loss of facial muscle power and sensory loss over anterior 1/3 of tongue); vagus nerve (exaggerated gag reflex, breathing difficulty and palpitations) and glossopharyngeal nerve (loss of taste over posterior 2/3 of tongue). Table 1 shows the possible cranial nerve involvements in her condition; this was gleaned from her history and examination.

She was self-ambulatory [Huges (4) grade 1]. There was no sensory loss or motor weakness in her extremities. Her muscle tone was normal. Her deep tendon reflexes were brisk in biceps, triceps as well as in ankle jerks and normal response was felt in others. Her plantar responses were flexor on both the side. Abdominal reflex was normal.

She was only able to hold breath for 19 counts, which indicated that reduction in her vital capacity. Her facial muscle function evaluated using House Brackmann grading system [

5], which was grade III on her left side face and grade V on her right side face. We also administered subscale of facial disability index (FDI) to measure her social function and her score was 52%. FDI is a self-reported, disease-specific instrument designed to provide the clinician with information about the disability and related social and emotional well-being of patients with facial nerve disorders [

6].

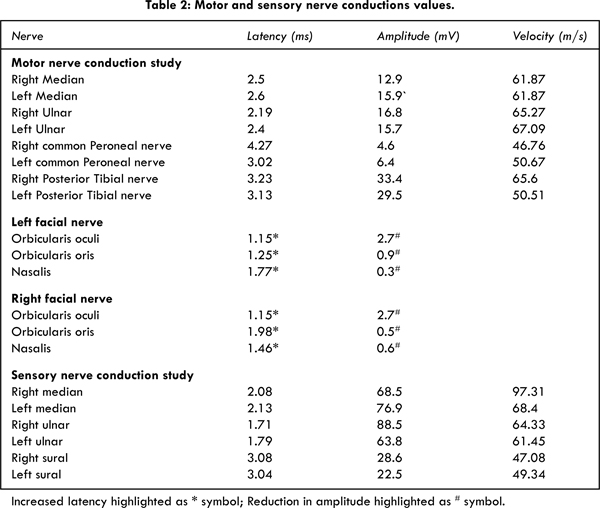

Nerve conduction study (NCS) revealed normal Compound Muscle Action Potential (CMAP) and amplitude in her upper and lower extremities. Table 2 shows the NCS values of facial nerve and extremities. Facial nerve showed moderate demyelination on both the side. No other invasive serological and cerebrospinal fluid examination were seen, as her duration of injury was more than two months. Most of the values would have been normalized by this time. Antiganglioside antibodies were not sent and no imaging studies of the brain were carried out, as her presentation was consistent with a demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. We were not able do any kind of test to correlate her clinical presentation with the serological values except the NCS.

The chances of administering intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange were minimized in her condition, as it is not an early diagnosis. Due to this reason, she was treated only with steroids for two weeks and was instructed to continue the physical therapy exercises. Over the period, her facial asymmetry got reduced. In her eighth week’s review with us, her House Brackmann grading was I on her left side and grade II on her right side. Her social function score increased to 92%. With the intensive physiotherapy treatment, her physical and social functions have reached near to the normal.

Discussion

Isolated facial diplegia is always going to be a diagnostic dilemma as various systemic conditions brings out this presentation. The possible systemic conditions causes this kind of presentation are Bell’s palsy, sarcoidosis, lyme disease, Hansen’s disease (leprosy), diabetes mellitus, brainstem encephalitis, brainstem stroke, herpes zoster (Ramsay Hunt and Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome), HIV and GBS.

Keane, [

1] in a 23-year review, found that out of 43 patients with bifacial palsy as the predominant sign, bilateral Bell’s palsy (10/43) and GBS (5/43) were the most common underlying causes. Among the cases, two out of the five with GBS progressed clinically; information on the others was not available. In our patient, the weakness remained localized to the face with no clinical evidence of progression. The absence of blink reflexes (RI and R2) indicated an abnormality in the trigemino-facial reflex arc on both sides.

A careful history collection and a complete neurological evaluation will help us to make differential diagnosis. In our case, key points which were suggestive of the variant of GBS are history of upper respiratory infection three days before the first occurrence of facial palsy; involvement of cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X and simultaneous facial diplegia with the second occurrence within one month duration.

A case report of Sethi et al, demonstrates similar features of simultaneous facial diplegia and hyperreflexia with preserved motor and sensory functions on the extremities. Hyper-reflexia as a variant in GBS has also been described and is currently not thought to be inconsistent with the diagnosis [

7-

9]. It is thought to be due to increased motor neuron excitability and spinal inhibitory interneuron dysfunction. Preservation of reflexes is considered to be a good indicator for recovery [

10].

In our case, the first and second visited neurophysician who first saw her presentation, concluded as Bell’s palsy. By the time she reached us, her disability had lasted for more than two months, and she suffered considerable distress and the condition resulted in her isolating herself even from her family members.

This type of presentation frequently gets misdiagnosed as the examiner misses important signs and symptoms, which could lead to the diagnosis. The evaluation should done by keeping in mind the differential diagnosis and the physician should ensure that he has ruled out the disorders, which could mimic the conditions at hand. A complete neurological examination does not end with examining the various neural components. It is complete by evaluating patient as a whole.

Conclusion

GBS should be considered as a differential diagnosis for facial diplegia even when there are brisk reflexes.

References

- Keane JR. Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: Analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature. Neurology 1994;44:1198-1202.

- Stahl N, Ferit T. Recurrent bilateral peripheral facial palsy. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:117–119.

- Adour KK, Byl FM, Hilsinger RL, Kahn ZM, Sheldon MI. The true nature of Bell’s palsy: analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients. Laryngoscope. 1978; 88:787–801.

- Hughes RA, Newsom-Davis JM, Perkin GD, Pierce JM. Controlled trial prednisolone in acute polyneuropathy. Lancet. 1978;2:750-753.

- Reitzen SD, Babb JS, Lalwani AK. Significance and reliability of the House-Brackmann grading system for regional facial nerve function Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:154-158.

- VanSwearingen JM, Brach JS. The Facial Disability Index: reliability and validity of a functional assessment instrument for dis orders of the facial neuromuscular system. Phys Ther. 1996;76:1288-1300.

- Sethi KN, Josh Torgovnic, Edward Arsura, Alissa Johnston, Elizabeth Buescher. Facial diplegia with hyperreflexia-a mild Guillain-Barre Syndrome variant, to treat or not to treat? Journal of Brachial Plexus and Peripheral Nerve Injury. 2007;2:9.

- Susuki K, Atsumi M, Koga M, Hirata K, Yuki N. Acute facial diplegia and hyperreflexia, A Guillain-Barré syndrome variant. Neurology. 2004;62:825-827.

- Singhal V, Bhat KG. Guillian Barre syndrome with hyperreflexia: A variant. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6:144-145.

- Kuwabara S, Mori M, Ogawara K, Hattori T, Yuki N. Indicators of rapid clinical recovery in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:560–562.