6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff6474350000006d07000001000500

6go6ckt5b5idvals|3091

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is a uncommon cutaneous lesion which resembles benign tumor. It is a nevoid proliferation of vascular, eccrine, and occasionally fatty tissues and pilar structures. Even though congenital and elderly cases have been reported, EAH commonly presents in children and young adults. Generally, it is located in the distal area of the extremities, and may be in the shape of a nodule or a tumorous plaque on the dermis [

1-

4]. The diagnosis of the present case was confirmed with the histopathological examination of the cutaneous lesion that caused swelling and pain.

Case Report

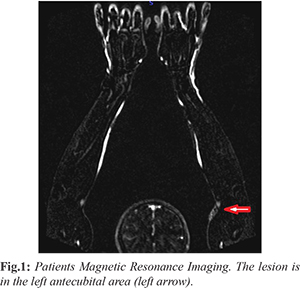

A 27-year-old man presented to our polyclinic with complaints of a painful tubercle of firm consistency that had been growing for 2 years in the left antecubital fossa. After the clinical evaluation, ultrasonography (USG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of the lesion led to a possible diagnosis of a hemangioma [Fig.1]. We decided that bulk excision was appropriate after other pathologies were ruled out by physical examination and laboratory test findings. After obtaining informed consent, the 3×2×2 cm tumor was removed in a day case surgery along with light brown subcutaneous vascular structures located in the subcutaneous area. The wound had completely healed at a follow-up visit 15 days later, and the antecubital fossa was normal. No relapse was observed after 2 years.

The specimen was histopathologically examined and confirmed on immunohistochemistry. On the macroscopic examination a 3×2×2 cm dark brown tissue sample was observed, whose cross-section had a bleeding appearenge. On the microscopic examination we observed a proliferous eccrine gland structure in the myxoid stoma, with mature adipose tissue [Fig.2]. The lesion was generally dilated and had congested thin-walled vascular structures formed by scattering between thick collagen bundles [Fig.3,4]. Cellular atypia and mitotic activity were absent. The lesion showed a continuous surgical border.

Discussion

EAH is a rare benign cutaneous hamartoma that consists of a proliferation of thin walled vascular canals. It was first defined as an angiomatous-appearing lesion by Lotzbeck in 1859 and exactly defined in 1968 by Hymen et al. [

2,

5-

7]. To date, approximately 220 cases of EAH have been reported worldwide by the Pubmed database. It is generally seen in the distal extremities of children. It occurs at the same rate in both sexes, and lesions can exist at birth or develop during pre-adolescence. The frequency is low at higher ages, but it can be seen at all ages [

4-

6,

8]. The lesions can be in the form of a single nodule or as a solitary tumorous plaque on the dermis [1,3,4,8]. Typically, they are in the form of skin-colored, blue-brown, reddish papules, plaques or nodules, and can be seen as macular rash or hyperkeratosis at more than one location on the body [

6,

8].

Although the origin of EAH is unknown, the congenital form is thought to involve a defective biochemical interaction between the differentiated epithelium and underlying mesenchyme during early organogenesis, leading to a proliferation of abnormal adnexal and vascular structures. There are various theories for its etiology such as an abnormal induction of heterotypic dependency with resultant malformation of the adnexal as well as mesenchymal elements [

8-

10]. Growth and proliferation of lesions in puberty and pregnancy suggests that hormonal factors can affect the disease [

10]. Late-onset lesions can be related to recurrent trauma [

8-

10]. There was no majör or recurrent trauma story in our case.

EAHs are generally asymptomatic; however, pain, hyperhidrosis, and hypertrichosis are the most commonly encountered symptoms [

5,

6,

8]. The pain is probably a consequence of infiltration of small nerves. Hyperhidrosis may develop because of a local temperature increase due to proliferation of the veins and increase in the number of free glands. Martinelli et al. [

6] conducted a literature search and recorded the results of 42 patients; the detected pain in 42%, hyperhidrosis in 32%, and both symptoms in 17%. In our case, the tubercle, which was in the antecubital fossa for 2 years, had been getting bigger, and painful symptoms had emerged in the last 6 months. On the histopathological examination, the lesion contained well differentiated proliferous eccrine glands, thin-walled and dilated vascular structures, and mature oil cell groups, as well as general mucinosis in the stroma. The glands were unencapsulated in the middle and deep dermis [

1-

7]. The vascular structures are generally thin-walled, but may be thick-walled (some parts are irregular) in some lesions [

7]. The histomorphological signs of our case were consistent with those observed in previous cases. For diagnosis, although ultrasound (USG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with physical examination can be used, the final diagnosis is established only by histopathology [

2,

4,

6]. We initially used USG and MRI for making the diagnosis. Although the diagnosis was not certain, it was thought to be a hemangioma because of the workup findings and was hence totally excised. The associated findings consistent with EAH, such as lesion enlargement, hypertrichosis, hyperhidrosis, pain, and itching, can provide valuable diagnostic clues to help differentiate EAH clinically from vascular malformations, hamartomas, hemangiomas, tufted angiomas, smooth muscle hamartomas, glomus tumors, and blue rubber bleb nevi. Unlike in EAH, there is no significant eccrine proliferation in sudoriferous angiomas, which should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Eccrine glands exhibit dilatation in EAH [

8].

The treatment for symptomatic cases of EAH is total excision. Cutaneous grafting or amputation may be required; embolization can be applied before the operation [

8,

9]. Asymptomatic cases can be followed-up. Botulinum toxin, intra-lesional sclerosant injection and laser can also be used as treatments [

8,

9,

11]. Lin et al. [

8] and Sanusi et al. [

9] used surgical excision for 11 of 15 and 22 of 26 patients, respectively, as reported in their published series. A post-operative relapse was observed in the first study, and a patient required limb amputation in the second study. In our case, relapse was not observed during 2-years follow-up.

Conclussion

EAH is a benign non-neoplastic skin lesion. Because of symptoms such as pain and hyperhidrosis and cosmetic reasons require treatment. Surgical excision is usually sufficient in the treatment. Skin grafting may be necessary in some cases, and tissue loss may occur in some cases.

Contributors: ESC, FB: conception or design of the work, manuscript writing, patient management; SO: conception or design of the work, manuscript editing, histopathology; UA, BE: conception or design of the work, critical inputs into the manuscript. ESC will act as a study guarantor. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of this study.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Sanmartin O, Botella R, Alegre V, Martinez A, Aliaga A. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:161-164.

- Laeng RH, Heilbrunner J, Itin PH. Late-onset eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: clinical, histological and imaging findings. Dermatology. 2001;203:70-74.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, Lin AN. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Asiran Serdar Z, Mansur AT, Pekcan Yasar S, Göktay F, Barutcugil B, Günes P. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: case report. Turkiye Klinikleri J Dermatol. 2008;18(1):40-43.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler MB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Martinelli PT, Tschen JA. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;71:449-455.

- Tsunemi Y, Shimazu K, Saeki H, Ihn H, Tamaki K. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with massive mucin deposition. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:291-292.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, Chuang YH. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Sun L, Wang C, Zhou Y, Huang C. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a clinicopathological study of 26 cases. Dermatology. 2015;231:63-69.

- Mendiratta V, Malik M, Agrawal M, Jain M, Gupta B. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: A rare entity revisited. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:188-190.

- Felgueiras J, del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Bonet Mdel M. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: successful treatment with pulsed dual-wavelength sequential 595- and 1,064-nm laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:428-430.