|

Baian Alhindawi, Kimberley Nash, Jude Jose The Fertility Unit at Luton and Dunstable Hospital NHS Trust, Luton, United Kingdom.

Corresponding Author:

Dr Baian Alhindawi Email: baianalhindawi@hotmail.com

Abstract

Background: Ureteral endometriosis commonly presents with non-specific symptoms or no symptoms. Diagnostic challenges are multifactorial but essentially caused by diagnostic delay due to the silent nature of the disease. Management requires a multidisciplinary approach to optimise the outcome. Case Report: A 29-year-old woman presented with severe deep infiltrating endometriosis resulting in bilateral hydronephrosis and loss of left kidney function. Laparoscopic excision of deep infiltrating endometriosis, ureterolysis, bowel resection and colostomy formation were performed. Eventually the left non-functional kidney required nephrectomy. Conclusion: The presence of posterior deep infiltrating endometriosis with uterosacral involvement should increase clinical suspicion of ureteral endometriosis and trigger targeted investigations. The best outcome is achieved by the individualisation of patient’s care.

|

6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff68e5370000006207000001000b00 6go6ckt5b5idvals|3123 6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Endometriosis affects 2-10% of the reproductive age female population and up to 50% of sub-fertile women [1]. Common symptoms associated with endometriosis include cyclical pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea, deep dyspareunia and cyclical intestinal upset. Additional symptoms include dyschezia, rectal bleeding, dysuria and haematuria which can be suggestive of the location of the endometriosis, however, the symptoms may also be very non-specific [1-3]. Involvement of the urinary tract is seen in 1-5% of women with endometriosis having urinary tract involvement [4]. Ureteral endometriosis is an uncommon but serious condition that may lead silently to obstruction of the urinary tract leading to hydronephrosis, hydroureter and potential loss of kidney function. The literature reported cases of ureteral endometriosis with various degrees of renal damage and management with different surgical interventions [4]. Ureteral endometriosis is often associated with extensive endometriosis especially ovarian endometriomas, deeply infiltrating endometriotic (DIE) lesions, and the involvement of uterosacral ligaments. Diagnosis is often challenging due to the silent nature of the disease and the presence of nonspecific or no symptoms [5].

Case Report

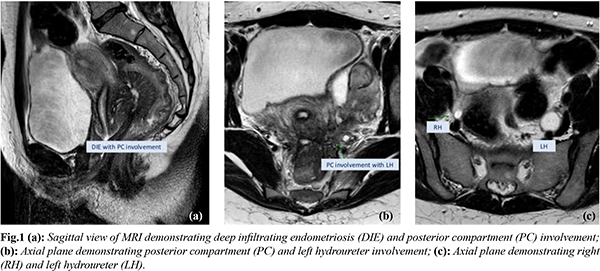

A 29-year-old female and her 36-year-old male partner presented to the subfertility team with a 2-year history of primary subfertility. The patient had a long-standing background history of congestive dysmenorrhoea and menorrhagia which was managed with the contraceptive pill. The patient stopped the pill as she wanted to conceive. The previously mentioned symptoms resumed and she progressively started to experience dyspareunia and cyclical rectal bleeding for a period of almost 2 years prior to seeing her GP. No urinary symptoms were reported. The symptoms triggered investigations by her general practitioner (GP) for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Upon referral to the fertility clinic, she underwent an initial assessment. The gynaecology examination was unremarkable. Screening tests into subfertility were instigated for the couple. A hormone profile suggested anovulation with a 21-day progesterone and a pelvic ultrasound scan (USS) revealed bilateral endometriomas. In the absence of urinary symptoms, the USS study did not involve the urinary tract system examination. In view of her symptoms and the finding in the USS, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis was performed to assess for the presence of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE). This revealed severe deep infiltrating endometriosis, multiple endometriomas were identified on both ovaries with involvement of the uterosacral ligaments and rectum, and there was mass like involvement of the pelvic sidewalls with encasement of the right ureter and encasement and obstruction of the left ureter resulting in bilateral hydronephrosis and thinning of the left kidney parenchyma. Reaching the final diagnosis took 6 months from the initial referral. As a result of these findings, kidney function was assessed. Creatinine levels were raised at 104 mmol/L. An urgent discussion took place with the urology team and a renal DMSA scan was performed. This demonstrated a normal right kidney with minimal function of the left kidney. An urgent bilateral ureteric stenting was performed by the urologists. Further joint surgical intervention following a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) review was undertaken with the colorectal and urology team. Laparoscopic excision of deep infiltrating endometriosis, ureterolysis, bowel resection and colostomy formation were performed. Following surgical intervention, a renal DMSA scan was performed. No improvement was seen, with less than 6% function of the left kidney. As a result, a left nephrectomy was performed by the urology team and reversal of the loop colostomy by the colorectal team. Following a successful post-operative recovery, the couple were referred for in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) and achieved a successful pregnancy.

Discussion

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of active endometrial tissue, glands and stroma deposited outside the uterine cavity resulting in a chronic inflammatory reaction [6]. The endometrial tissue is most commonly confined to the pelvis. However, extra-pelvic locations can include the lungs, lymph nodes and kidneys [7,8]. The bladder is involved in 70-85% of cases, whereas 9-23% of urinary tract endometriosis involves the ureters making it the second most common site after the bladder. The left ureter is more frequently affected than the right with bilateral involvement seen in 20-25% of cases [1]. About 90% of ureteric endometriosis is associated with primary endometriosis in other sites. 50-70% of cases are associated with ovarian endometriomas, 45-55% with DIE like rectovaginal space and 10-50% with uterosacral ligaments [5]. Endometriosis of the ureter has been suggested to arise from the extension of endometriotic lesions within the pelvis, with the presence of ovarian endometriomas and the involvement of the uterosacral ligaments being a pre-requisite for ureteral disease in many cases due to the close anatomical relation [7,9]. Ureteric endometriosis is divided into intrinsic or extrinsic disease. The extrinsic disease is four times more common and involves endometrial tissue encasing the surrounding connective tissue and subsequently obstructing the ureter and causing hydronephrosis. The intrinsic disease is rare and found to be more symptomatic. With intrinsic disease, endometriotic glands and stroma are found in the muscularis layer and uroepithelium of the ureter. Both types can present concurrently [3,8,9]. Women with ureteral endometriosis can present with a wide range of non-specific symptoms such as cyclical pelvic pain, significant dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia and up to 50% of women are completely asymptomatic [ 10]. Specific urinary symptoms associated with ureteral endometriosis represent only 9-16% of patients. These include flank pain, renal colic, cystitis and haematuria, but women remaining asymptomatic may present later with unexplained hypertension and renal failure [ 1]. This represents the poor correlation between the degree of urinary symptoms and the severity of ureteral endometriosis. Moreover, many cases were found incidentally at the time of laparoscopic surgery for excision of extensive endometriosis [ 11].

Ureteral endometriosis can pose a diagnostic dilemma and the consequences of the undiagnosed disease can result in severe morbidity. One of the diagnostic challenges faced is the delay in clinical presentation leading to a hindrance in obtaining the relevant investigations. Having non-specific symptoms that overlap with many gynaecologic, gastroenterological and urologic conditions mislead the investigations and can result in significant diagnostic delays. Additionally, there is a lack of patient awareness and uncertainty about endometriosis symptoms, an embarrassment of reporting and stigmatisation [ 12- 14]. Furthermore, clinician-centred factors such as underestimation of patient’s symptoms and the financial burden in primary care, lead to suboptimal utilisation of the diagnostic tools and the referral system. This by far has a negative impact on patient care. Studies suggested severe diagnostic delays up to 6-7 years largely related to late primary care referral to a specialist [ 13] and over 4 years of diagnostic delay by a specialist [ 15]. This was apparent in our case. The patient had over 2 years of symptoms suggestive of endometriosis without any relevant investigations and a subsequent process of subfertility referral and investigations took 6 months to reach a diagnosis. By the time the patient suffered adverse outcomes and irreversible morbidity.

Diagnostic modalities include pelvic ultrasound scan (USS) as first-line. It is a non-invasive and cost-effective tool. With trained hands, transvaginal ultrasound scans can improve the detection of deep infiltrating endometriosis [4,16]. Hydronephrosis and ureteral stenosis associated with ureteral endometriosis can be evaluated on abdominal USS [16]. With continual developments in the identification of DIE on USS, and due to the high association between DIE and ureteral endometriosis, it has been suggested that ultrasound assessment of the kidneys and ureters should be included as part of the assessment in women who have a suspicion of DIE or ovarian endometriomas [4]. This suggestion optimises the early diagnosis if introduced in primary care. MRI is highly reliable in the detection of DIE and considerably accurate in the recognition of the type of ureteral endometriosis with a possibility of overestimation of intrinsic ureteral involvement [17]. Furthermore, it is a valuable tool in the pre-surgical staging, patient’s counselling of possible complications and surgical planning.

Multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach is essential in the management of ureteral endometriosis due to the complexity in such cases, especially in a young female population where it commonly presents. Treatment depends on disease severity, renal function, the degree of hydronephrosis and reproductive wishes. Minimal disease can be managed with hormonal treatment, which suppresses ovarian function, however, the incidence of recurrence is high and hormonal treatment is not recommended in those with severe disease. Hormonal treatment is not effective in the presence of coincident DIE and surgical intervention is required ultimately to excise the disease, relieve symptoms and ease ureteral obstruction [10]. The surgery is complex and requires the expertise of gynaecologists, urologists and colorectal surgeons. Evidence is limited with regards to the most appropriate surgical intervention and is based on individual circumstances and MDT conclusion. Surgical intervention may consist of cystoscopy and ureteric stenting, ureteroneocystostomy, ureterolysis, ureteral resection and end-to-end anastomosis. Nephrectomy is considered in the presence of a non-functioning kidney. In cases of intrinsic ureteral disease, resection of the ureter involved is required [10]. Although complete excision of endometriosis is associated with improvement in symptoms, quality of life and overall reproductive outcomes. The direct impact of advanced endometriosis on fertility is not fully established [18].

Conclusion

Ureteral endometriosis is rare and can present primarily with kidney loss. The presence of posterior DIE with uterosacral involvement should increase clinical suspicion and trigger targeted investigations. USS and MRI are useful diagnostic modalities, especially in presurgical assessment. The early consideration of combining urinary tract system examination with pelvic ultrasound as a primary investigation tool especially in the presence of DIE offers a revolutionary step in the diagnosis. A multidisciplinary approach and experienced laparoscopic surgeons are key in the optimisation of outcomes.

Contributors: BA: Wrote the manuscript and did literature review; KN: Obtained the case details, contributed in writing the manuscript and did structural work arrangement; JJ: critical inputs into the manuscript. BA will act as a study guarantor. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of this study. Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References - Dunselman GAJ, Vermeulen N, Becker C, Calhaz-Jorge C, D'Hooghe T, De Bie B. et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with endometriosis. September 2013. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:400-412.

- Nezhat C, Paka C, Gomaa M, Schipper E. Silent loss of kidney secondary to ureteral endometriosis. Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2012;16(3),451-455

- Yohannes P. Ureteral endometriosis. J Urol. 2003;170:20-25.

- Reid S, Condous G. Should ureteic assessment be included in the transvaginal ultrasound assessment for women with suspected endometriosis. Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2015;18(1):2.

- Seracchioli R, Raimondo D, Di Donato N, Leonardi D, Spagnolo E, Paradisi, R., et al. Histological evaluation of ureteral involvement in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis: analysis of a large series. Human Reproduction, 2015;30(4):833-839.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):511-519.

- Cornillie FJ, Oosterlynck D, Lauweryns JM, Korninckx PR. Deeply infiltrating pelvic endometriosis: Histology and clinical significance. Fertility and Sterility. 1990;53:978-983.

- Chapron C, Chiodo I, Leconte M, Amsellem-Ouazana D, Chopin N, Borghese B, Dousset B. Severe ureteral endometriosis: the intrinsic type is not so rare after complete surgical exeresis of deep endometriotic lesions. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;93(7):2115-2120.

- Abrao MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA, Jr., Averbach M, Silva LF, Marino de Carvalho F. Endometriosis lesions that compromise the rectum deeper than the inner muscularis layer have more than 40% of the circumference of the rectum affected by the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:280-285.

- Barra F, Scala C, Biscaldi E, Vellone VG, Ceccaroni M, Terrone C, et al. Ureteral endometriosis: a systematic review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, risk of malignant transformation and fertility, Human Reproduction Update. 2018;24:710-730.

- Vercellini P, Pisacreta A, Pesole A, Vicentini S, Stellato G, Crosignani PG. Is ureteral endometriosis an asymmetrical disease. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;107(4):559-561.

- Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296-301.

- Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, d’Hooghe T, Nardone FC, Nardone CC, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(366–73): e8.

- Cromeens MG, Carey ET, Robinson WR, Knafi K, Thoyre S. Timing, delays and pathways to diagnosis of endometriosis: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2021;11: e049390.

- Soliman AM, Fuldeore M, Snabes MC. Factors associated with time to endometriosis diagnosis in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017; 26:788-797.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, Van den Bosch T, Valentin L, Leone FPG, Van Schoubroeck D, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016;48(3):318-332.

- Balleyguier C, Roupret M, Nguyen T, Kinkel K, Helenon O, Chapron, C. Ureteral endometriosis: the role of magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, 2004;11(4):530-536.

- Somigliana, E, Garcia-Velasco JA. Treatment of infertility associated with deep endometriosis: definition of therapeutic balances. Fertility and Sterility. 2015;104(4):764-770.

|