|

Anurag Singh, Sanjay Mishra, Nida Shabbir, Akanksha Singh, Tanya Tripathi Department of Pathology, King George Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Anurag Singh Email: anugsvm@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background: Primary Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) is an infrequent subtype of aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, representing a small fraction of all lymphomas. Primary gastrointestinal B cell lymphomas are a rare subset of B cell lymphomas and are characterized by their aggressive behaviour and an unusual chromosomal rearrangement (11;14) with overexpression of cyclin D1. The initial presentation of primary MCL as rectal nodules is an exceptionally uncommon, and sparsely documented in medical literature. Case Report: A 59-year-old male patient who presented with symptoms of rectal bleeding, constipation, and abdominal pain that persisted for four months is the subject of this case report. A subsequent colonoscopy revealed distinct features such as edema, loss of vascularity, nodularity, and central ulceration encircling the rectal region. A punch biopsy was performed on the affected area, followed by a comprehensive histopathological examination. Based on the distinctive histomorphology and immunohistochemistry findings of the biopsy specimen, a diagnosis of MCL was conclusively established. Conclusion: This case serves as a reminder that lymphoproliferative neoplasms, including MCL, should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients who present with rectal bleeding and rectal nodularity, especially in older individuals. Immunohistochemistry plays a vital role in the definitive diagnosis, as clinical symptoms and colonoscopy findings may mimic those of rectal cancer.

|

Introduction

Mantle cell lymphoma is an aggressive low-grade B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with a prevalence of approximately 6% of all NHL [ 1]. The incidence rate of MCL is 0.8 per 100,000 people, according to the SEER database (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program) [ 2]. According to a previous retrospective study, the prevalence is 5.6% in the Indian population [ 3]. The median age at presentation is between 60 and 65 years, and it is more prevalent in men. Having a pathognomonic chromosomal translocation (11;14) and overexpression of cyclin D1 are hallmarks of the uncommon and aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma known as mantle cell lymphoma [ 4]. Prior to the introduction of rituximab antibody treatment and autologous stem cell transplantation (SCT), the prognosis for MCL was generally poor; now, results have considerably improved with long-term disease-free survival [ 4- 6]. Histomorphology, immunohistochemistry, and evidence of overexpression of the cyclin-D1 MCL protein by immunophenotyping and/or fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) are used to make the diagnosis of MCL [ 7]. In this rare case report, our primary aim was to describe the rare presentation of MCL patients as rectal nodules and to discuss the histomorphology, immunophenotyping, and options for treatment for such patients.

Case Report

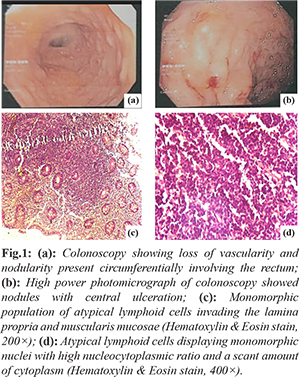

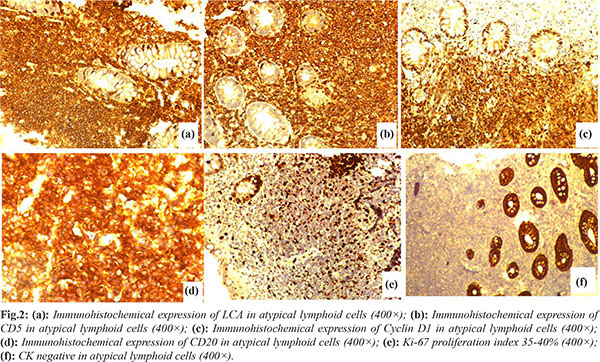

We report a 59-year-old man who presented to the gastroenterology unit with chief complaints of rectal bleeding, constipation, and abdominal pain over the previous four months. There were no B symptoms. Hemogram, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, urea, creatinine, electrolyte levels, and coagulation profile were all in the normal range. A colonoscopy revealed erythema, edema, loss of vascularity and nodularity with central ulceration present circumferentially involving the rectum [Fig.1a,b]. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the thorax and abdomen was ordered, which showed no organomegaly and lymphadenopathy. On the basis of clinical presentation and colonoscopy findings, differential diagnoses of rectal carcinoma and lymphoma were kept in mind. A colonoscopy-guided punch biopsy of the rectal lesion was ordered based on the clinical manifestation and endoscopic findings. Histopathological analysis of the hematoxylin-eosin (H-E) stained sections from colonoscopy guided punch biopsy revealed diffuse infiltration of the lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae by atypical small-sized lymphoid cells disposed in nests and sheets displaying irregular nuclei, coarse chromatin, and a scant amount of cytoplasm [Fig.1c,d]. Based on the above histomorphology, we made the differential diagnosis of poorly differentiated carcinoma, small cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma. An immunohistochemistry panel was applied which showed positive expression of leucocyte common antigen (LCA/CD45), CD20, CD5, and cyclin D1 in atypical lymphoid cells. Ki67 proliferation was 35-40%. CD3, CD10, and cytokeratin (CK) were negative in atypical lymphoid cells [Fig.2]. Based on the above histomorphology and immunohistochemistry, a diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma was rendered. A bone marrow examination was also performed to stage the disease, which revealed normal haemopoiesis and was negative for lymphomatous infiltration. 18-fluorodeoxyglucose did not show uptake in any organ of body on PET scan. He was referred to the Clinical Hematology department for chemotherapy. The patient had received two cycles of rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) therapy and currently doing well.

Discussion

The mantle cell type of the neoplastic lymphoid neoplasm was identified in 1984 [ 8, 9]. In the Romaguera et al. study, it was noted that 88% of MCL patients had lower gastrointestinal system (GIS) involvement, compared to 43% of MCL patients who had upper GIS involvement [ 9]. The colon and rectum (57.1% and 47.6%, respectively) for the lower GIS and the stomach mucosa (74%) for the upper GIS are the most frequently affected sites. According to the endoscopic examination of the lesions within the GIS, the multiple lymphomatous polyposis (MLP) type is the most prevalent type (80%), whereas protruding nodular lesions are less common (18%). [ 10, 11]. The endoscopic appearance of lesions is very variable and the clinical signs are non-specific; polyps, rectal ulcers, a solitary mass, or widespread mucosal thickening may all be present in addition to normal mucosa. Morbidity and death are prevalently high among cases of MCL associated with the gastrointestinal system [ 12]. Men are more likely to be affected, and symptoms often appear in their fifth or sixth decade of life [ 13]. Abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, or haematochezia symptoms are frequently present. The majority of patients have extra-intestinal involvement and are present at an advanced stage. The bone marrow, peripheral lymph nodes, liver, and Waldeyer's ring, are the primary extra-gastrointestinal sites affected [ 14, 15]. The atypical lymphoid cells in MCL are small to medium-sized and display uneven nuclear outlines, coarse chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and a scant cytoplasm [ 14]. Mantle cell lymphoma express CD5 and pan B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, and CD22) on immunohistochemistry but are negative for CD10 or CD23 expression. Despite the fact that 84% of mantle cell lymphoma patients, regardless of the existence of gastrointestinal symptoms, have some degree of microscopic gastrointestinal involvement [9], only 4 to 9% of all primary gastrointestinal B cell lymphomas are primary MCL [ 15]. Gastrointestinal mantle cell lymphoma is the most common cause of multiple lymphomatous polyposis (MLP). Even with the best treatment, multiple lymphomatous polyposis has a mean survival rate of about three years [ 16]. Considering present case, only manifestation of disease was per rectal bleed, abdominal discomfort and constipation. Since there was no involvement of any other organs or abdominal lymph nodes, it was classified as primary gastro-intestinal lymphoma. His blood workup was also within the normal range, and he had no palpable peripheral lymph nodes. Endoscopic examination of our patient's gastrointestinal system revealed several circumferential nodular lesions rather than the typical picture of multiple lymphomatous polyposis. The current treatment plan is based on clinical risk factors, symptoms, and stages of the disease. An aggressive frontline immunochemotherapy induction regimen combining rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) and a high dose of cytarabine is advised for patients younger than 65 years of age who are in good condition. Conventional immunotherapy (R-CHOP) followed by rituximab is the gold standard for the group of elderly patients or those in poor health [17,18]. Unfortunately, remissions are frequently brief, the likelihood of recurrence is high, and the median survival is only 3 to 4 years, despite the high response rate to aggressive chemotherapy regimens that typically result in the regression of macroscopic and occasionally microscopic lesions [15]. Unsatisfactory clinical status, involvement of several extra-nodal locations, advanced age (greater than 70 years), increased lactate dehydrogenase levels, and bone marrow infiltration are all indicators of a poor prognosis [18].

Conclusion

Lymphoproliferative neoplasm should be considered in the differential diagnosis if patients present with rectal bleeding with rectal nodularity, especially at an advanced age. Immunohistochemistry is a great way to make definitive diagnosis, because symptoms and results of a colonoscopy and histomorphology findings may mimic with rectal carcinoma.

Contributors: AnS did study designing, data acquisition, manuscript writing and literature search. SM did a literature search and proof correction. NS did conceptual analysis and designing. AkS did proof reading. TT contributed to literature searches. SM will act as a study guarantor. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of this case study. Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References - Das CK, Gogia A, Kumar L, Sharma A, Sharma MC, Mallick SR. Mantle cell lymphoma: a north Indian tertiary care Centre experience. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2016;17(10):4583.

- Howlader NN, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2010. National Cancer Institute. 2014 Jan 28. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2010/. Accessed on July 23, 2022.

- Naresh KN, Srinivas V, Soman CS. Distribution of various subtypes of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in India: A study of 2773 lymphomas using REAL and WHO Classifications. Annals of Oncology. 2000;11:S63-67.

- Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, Wörmann B, Dührsen U, Metzner B, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1984-1992.

- Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, Broglio KR, Hagemeister FB, Pro B, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):7013-7023.

- Delarue R, Haioun C, Ribrag V, Brice P, Delmer A, Tilly H, Salles G, et al. CHOP and DHAP plus rituximab followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 study from the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2013;121(1):48-53.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375-2390.

- Kelkitli E, Atay H, Yildiz L, Bektas A, Turgut M. Mantle cell lymphoma mimicking rectal carcinoma. Case Rep Hematol. 2014;2014:621017.

- Romaguera JE, Medeiros LJ, Hagemeister FB. Erratum: Frequency of gastrointestinal involvement and its clinical significance in mantle cell lymphoma (Cancer (2003) 97 (586-591)). Cancer. 2003;97(12):3131.

- Iwamuro M, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Shinagawa K, Morito T, Yoshino T, et al. Endoscopic features and prognoses of mantle cell lymphoma with gastrointestinal involvement. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(37):4661.

- Chittmittraprap S, Intragumtornchai T, Wisedopas N, Rerknimitr R. Recurrent mantle cell lymphoma presenting as a solitary rectal mass. Endoscopy. 2011;43(S02):E284-285.

- Martin-Dominguez V, Mendoza J, Diaz-Menendez A, Adrados M, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, et al. Colon lymphomas: an analysis of our experience over the last 23 years. Revista Espanola de Enfermadades Digestivas (REED). 2018;110(12):762-768.

- Arieira C, Castro FD, Carvalho PB, Cotter JA. Primary colon mantle lymphoma: a misleading macroscopic appearance. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111(12):965-967.

- Khuroo MS, Khwaja SF, Rather A, Hassan Z, Reshi R, Khuroo NS. Clinicopathological profile of gastrointestinal lymphomas in Kashmir. Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 2016;37(04):251-255.

- Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Audouin J. Primary gastrointestinal tract mantle cell lymphoma as multiple lymphomatous polyposis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 2010;24(1):35-42.

- Vignote Ml, Chicano M, Rodriguez FJ, Acosta A, Gómez F, Poyato A, et al. Multiple lymphomatous polyposis of the GI tract: report of a case and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:579-582.

- Martins C, Teixeira C, Gamito É, Oliveira AP. Mantle cell lymphoma presenting as multiple lymphomatous polyposis of the gastrointestinal tract. Revista brasileira de hematologia e hemoterapia. 2017;39:73-76.

- Waisberg J, Anderi AD, Cardoso PA, Borducchi JH, Germini DE, Franco MI, et al. Extensive colorectal lymphomatous polyposis complicated by acute intestinal obstruction: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2017;11(1):1-6.

|