Introduction

Persistent urogenital sinus (UGS) anomalies are one of the more complex problems, and they occur in a spectrum [1]. In these anomalies there is a persistent communication of the vagina with the urinary tract. This communication between the vagina and the urinary tract may occur at any point from the urethral meatus to the bladder, but the majority occurs within the mid to distal portion of the urethra. The two structures join and exit on the perineum as a single common urogenital sinus channel [1]. Regardless of how the confluence of the urinary and genital tracts is described, the confluence location in relation to the bladder neck is a more critical factor in surgical management than the length of the common channel [2]. In urogenital sinus anomalies the location of the anus is usually in the normal location, however anterior displacement is not uncommon, and this bridges the gap to cloacal anomalies [1].

The three steps in surgical reconstruction are clitoroplasty, vaginoplasty, and labioplasty. Surgical management is tailored according to the anatomical characteristics of the individual case as well as the presence of coexisting genitourinary anomalies. In most cases the low UGS could be successfully treated with a simple flap vaginoplasty [3]. In cases of intermediate UGS, characterized by a higher confluence of the urethra and vagina, but with acceptable urethral length (greater than 1.5 cm), an en bloc or total mobilization without jeopardizing urinary continence would be more suitable [4,5]. In cases with high UGS (1.5 cm or less) the application of this technique appears controversial. Some experts favor separating the vagina from the UGS confluence and pulling it through to the perineum [6]. The exposure of the urethrovaginal junction in such cases would be difficult and may result in complications (including strictures, diverticula, stenosis, incontinence and urethrovesical fistulas) [6,7]. We report on a case of high urogenital sinus with anteriorly displaced anus repaired by posterior sagittal approach.

Case Report

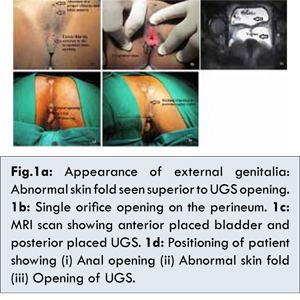

A sixteen year old adolescent girl approached the hospital gynecological services with complaints of passing bloody urine during menstruation. Physical examination revealed a single opening situated anterior to the anal verge in the perineum [Fig.1]. The child was continent for both urine and feces. The child’s milestones were normal and the child had no other obvious anomaly. Endoscopy revealed separate vaginal and urethral opening. The urethral length was adequate. As the anal verge was displaced anteriorly, it was decided to approach the repair through the posterior sagittal route.

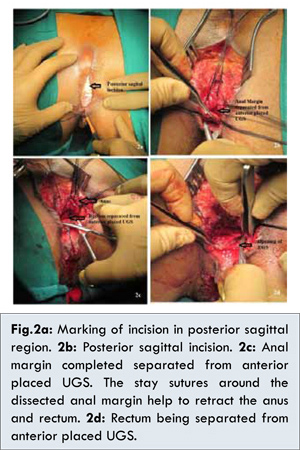

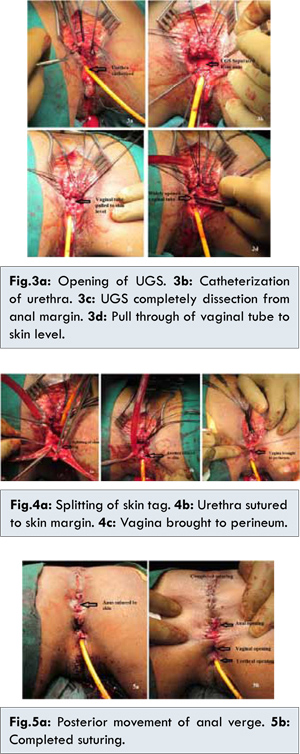

The child was prepared adequately for surgery. No preoperative bowel washes were given. Under general anesthesia the child was positioned in a prone, modified jackknife position [Fig.1d]. The position of the anal sphincteric activity was assessed using a muscle stimulator. A vertical incision posterior to the anal verge was made and the posterior wall of the anus and rectum was dissected [Fig.2]. The incision was continued to encircle the anal verge. The anus was dissected carefully so as to prevent damage to the anal sphincteric fibers. The dissection was continued anteriorly between the rectum and the urogenital sinus. A catheter was introduced into the vagina to facilitate the dissection [Fig.3]. The dissection was further carried around the urogenital sinus. This permitted the descent of the urogenital sinus towards the perineum. The urethra and the vagina were drawn down to the perineum. The urethral meatus and the vagina were sutured to the surrounding genital skin. No proper clitoral structure was noted and hence the tissue was left as it is. The excess skin tag at the anterior margin of the urogenital sinus was dissected and split in the middle to create labia minora on either side [Fig.4]. The anus was pushed posteriorly to place the anus as posterior as possible. The anus was sutured to the perianal skin. The final appearance showed the three openings of the urethra, vagina and anus [Fig.5].

The wound healed satisfactorily and the catheter was removed after 10 days. The child was continent for both urine and feces. The child was satisfied with the outcome and was happy with the appearance of her genitalia. The child answered positively to the questionnaire (modified outcome questionnaire) given to her [8].

Discussion

It is very important to know certain critical details of the anatomy in a child with urogenital sinus anomalies, including the length of the common urogenital sinus, the location of the vaginal confluence and its proximity to the bladder neck, the size of the vagina and the number of vaginas and the presence of a cervix. The bladder and urethral anatomy, must be defined adequately both by radiographic and endoscopic means. The location of the vagina in relation to the bladder neck is the critical issue in determining the type of surgery, and this distance is more important than the length of the common channel. A new urogenital sinus classification that measures the exact distance of the common channel and the distance of the bladder neck to the vagina has been devised to help delineate the exact level of the confluence, as well as clitoral size and appearance of the external genitalia [2].

Hendren and Crawford [6] proposed a complete separation of the vagina from the urogenital sinus with vaginal “pull-through” vaginoplasty as the best solution to a high vaginal confluence. The concept of vaginal separation and pull through as proposed by Hendren and Crawford appears theoretically simple, but it often resulted in an isolated vaginal opening which lacked mucosal lining. The critical and most technically demanding aspect of a pull-through vaginoplasty is separation of the anterior wall of the vagina from the urethra and bladder neck. There exists no proper plane of dissection, and great care needs to be taken to avoid injury to the urinary tract and its sphincteric mechanism. This area is also the most difficult to visualize, and poor exposure naturally leads to poor results, with the potential for a stricture, fistula, diverticulum, or retained distal vagina [1,2].

Pippi Salle et al. performed a retrospective review of a 6-year multi-institutional experience treating patients with a urogenital sinus anomaly using the anterior sagittal transrectal approach (ASTRA) without preoperative colostomy or prolonged postoperative fasting [3]. The study included a total of 23 children with a mean age of 2.3 years (range 3 months to 17 years) who underwent surgery between 2003 and 2010. Mean follow-up was 3.4 years (range 14 months to 7 years). All children had a high urogenital sinus with (16) or without (7) congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Only 1 anterior sagittal transrectal approach related complication was encountered when a perineal infection developed in a child and required temporary diverting colostomy without compromising the repair. All toilet trained patients were continent for feces and most were voiding normally per urethra (21), except for 2 with associated urological malformations. There were 15 patients who underwent follow-up examination under anesthesia, and demonstrated separate urethral and vaginal openings. The authors concluded that anterior sagittal transrectal approach provided excellent exposure for the management of a high urogenital sinus, facilitating the separation of urogenital structures. Good outcomes in terms of urinary/fecal continence as well as the absence of urethrovaginal fistulas were achieved in the majority of cases, supporting its consideration for the surgical management of this congenital abnormality.

The anterior sagittal transrectal approach (ASTRA) gradually became popular to treat urogenital sinus anomalies. It provided much better exposure however the morbidity associated with this technique could be potentially decreased if the anterior sagittal access were to be made without sectioning the rectum. Leite et al. reported on their initial experience using anterior approach without rectal sectioning and concluded that the technique was feasible and provided excellent exposure to the posterior urethra in most cases [9]. The technique was less morbid as it avoided the splitting and suturing of the anterior rectal wall.

The posterior sagittal approach as described in our case is a good access while dealing with urogenital sinus anomaly associated with anterior displacement of the anus. This access not only provides good exposure of the vagina and urethra, but also helps in positioning of the anus posteriorly. A band of skin can be mobilized easily in-between the anus and the vagina. The final appearance becomes more acceptable to the patient.

References

- Rink RC, Kaefer M. Surgical Management of Disorders of Sexual Differentiation, Cloacal Malformation, and Other Abnormalities of the Genitalia in Girls. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW and Peters CA ed Campbell-Walsh Urology, 10th Ed, Elsevier-Saunders, Philadelphia, 2012: pp. 3629-3666.

- Rink RC, Adams MC, Misseri R. Anew classification for genital ambiguity and urogenital sinus anomalies. BJU Int 2005;95:638-642.

- Pippi Salle JL, Lorenzo AJ, Jesus LE, Leslie B, AlSaid A, Macedo FN, et al. Surgical Treatment of High Urogenital Sinuses Using the Anterior Sagittal Transrectal Approach: A Useful Strategy to Optimize Exposure and Outcomes. J Urol 2012;187:1024-1031.

- Jednak R, Ludwikowski B, González R. Total urogenital sinus mobilization: a modified perineal approach for feminizing genitoplasty and urogenital sinus repair. J Urol 2001;165:2347.

- Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Tatsuo ES, Silva IN, Pippi Salle JL. Prospective evaluation of feminizing genitoplasty using partial urogenital sinus mobilization for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Urol 2006;176:2199.

- Hendren WH, Crawford JD. Adrenogenital syndrome: the anatomy of the anomaly and its repair. Some new concepts. J Pediatr Surg 1969;4:49.

- Peña A. Total urogenital mobilization - an easier way to repair cloacas. J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:263.

- Hoag CC, Gotto GT, Morrison KB, Coleman GU, MacNeily AE. Long-term functional outcome and satisfaction of patients with hypospadias repaired in childhood Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2(1):23-31.

- Leite MTC, Fachin CG, Maranhão RFA, Shida MEF, José Luiz Martins. Anterior sagittal approach without splitting the rectal wall. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:723–726.