Introduction

Tuberculosis remains highly prevalent in India, with many cases either left untreated or inadequately managed, often due to reliance on unqualified practitioners [

1]. Such mismanagement can lead to severe long-term complications, including lung fibrosis and collapse [

2]. We present a case of a patient with unilateral fibrotic lung collapse, likely secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis, who required emergency exploratory laparotomy. Anaesthetic management in such cases is particularly challenging, requiring meticulous intraoperative and postoperative strategies.

During general anaesthesia, special attention must be given to avoid barotrauma to the functional lung, as well as prevent complications such as pneumothorax, bronchospasm, and ventilation-perfusion mismatch [3]. Postoperative pain management is equally critical, as inadequate analgesia can further reduce lung volumes specifically functional residual capacity and vital capacity which may be especially detrimental in patients with compromised pulmonary reserve [4].

Case Report

A 35-year-old male presented to the emergency department with complaints of generalized abdominal pain for four days, associated with multiple episodes of vomiting, abdominal distension, and inability to pass flatus. He also reported increasing shortness of breath. The patient had a past history of pleural tapping around the age of 10 years and was a known case of pulmonary tuberculosis, for which he had taken irregular treatment and was currently not on any anti-tubercular therapy. He was a chronic smoker for the past 15 years, with a 15 pack-year history.

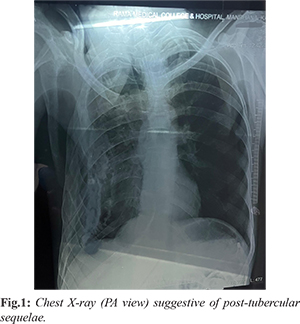

On clinical examination, the patient appeared thin-built, moderately nourished, and afebrile, lying in bed with knees flexed. There was no pallor or icterus. Respiratory examination revealed a sunken right chest wall with scoliosis and absent air entry on the right side, while breath sounds were normal on the left. Cardiovascular and central nervous system examinations were within normal limits, with a GCS of 15/15. Abdominal examination showed marked distension, tenderness, and guarding, with absent visible peristalsis. Initial vitals showed a heart rate of 120/min, blood pressure of 100/70 mmHg, and SpO2 of 94% on room air. Laboratory investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 9 g/dL, total leukocyte count of 15,000/mm³, and platelet count of 1.12 lakh/mm³. A chest X-ray (PA view) showed significant volume loss and architectural distortion in the right lung, with reticular opacities and calcified pleural thickening in the mid and lower zones, findings consistent with post-tubercular sequelae [Fig.1]. An erect abdominal X-ray revealed multiple air-fluid levels and dilated small bowel loops, suggestive of small intestinal obstruction. Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen demonstrated a proximal ileal stricture, trace ascites, and multiple enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, all indicating abdominal tuberculosis as the likely cause of the obstruction.

The patient was taken up for emergency exploratory laparotomy [Fig.2]. Standard ASA monitors were attached, and two wide-bore (18G) intravenous cannulas were secured. Preoperative assessment of tidal volume using a face mask on spontaneous mode showed a volume of approximately 180 mL and a respiratory rate of 20/min, giving an estimated minute ventilation of around 3-3.5 L/min. An epidural catheter was inserted at the T12-L1 interspace under aseptic precautions for postoperative analgesia. Premedication included intravenous glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg), midazolam (0.15 mg/kg), and fentanyl (1 mcg/kg). Rapid sequence induction was performed using ketamine (1 mg/kg), propofol (1 mg/kg), and succinylcholine (2 mg/kg). Endotracheal intubation was carried out using a 7.5 mm internal diameter tube. Air entry was confirmed on the left side; none was present on the right due to lung collapse.

The patient was ventilated in volume control mode with a tidal volume of 200 mL (approximately 4 mL/kg), respiratory rate of 16/min, I:E ratio of 1:2, and PEEP of 5 cm H2O. Isoflurane was administered at 0.5 MAC with 3 L/min of oxygen. Intraoperative parameters remained stable, with blood pressure of 130/90 mmHg, heart rate of 110/min, and oxygen saturation of 100%. Fluid balance and blood loss were carefully monitored throughout the procedure. At the end of surgery, which involved an ileostomy, 0.125% bupivacaine with 50 µg fentanyl was administered via the epidural catheter for postoperative analgesia. The patient was gradually weaned to spontaneous mode and demonstrated adequate respiratory efforts. Extubation was carried out smoothly once the patient was fully awake and hemodynamically stable. Post-extubation vitals were BP 100/70 mmHg, HR 100/min, and SpO2 98% on room air. The patient was shifted to the ICU for postoperative monitoring and observed for four hours without any complications.

Discussion

In Indian hospital settings, a significant number of patients present to the emergency department with acute abdominal conditions such as intestinal perforation or obstruction. These often necessitate emergency exploratory laparotomy, which involves major fluid shifts and, in some cases, extensive intestinal resection. Consequently, perioperative management requires meticulous attention to hemodynamics, electrolyte balance, and fluid management.

In our case, the patient had severe compromise of the right lung, likely a sequela of longstanding pulmonary tuberculosis, and was functionally dependent on a single lung. Administering general anaesthesia in such patients presents substantial risks, particularly the possibility of barotrauma and pneumothorax due to positive pressure ventilation. Tagera Tageza Ilala et al. have described a similar case managed successfully with epidural anaesthesia alone [5]. As spontaneous ventilation is maintained in such techniques, risks associated with positive pressure ventilation are minimized, making it a favorable option in select cases. However, the sole use of high-dose epidural anaesthesia may not be advisable in emergency surgical settings, particularly when the surgeon is less experienced, as it may lead to significant hypotension and bradycardia posing immediate risks to patient safety. Therefore, in our case, the epidural catheter was used solely for postoperative analgesia, a well-recognized benefit of neuraxial blocks [6]. Given that the patient had likely adapted to a single functional lung since adolescence and maintained a fair level of physical activity (METs score 3-4), we opted for general anaesthesia using a lung-protective ventilation strategy. Tidal volume was estimated preoperatively via mask ventilation under spontaneous breathing, revealing volumes around 180 mL. We employed low tidal volume ventilation (approximately 4 mL/kg) along with low-level positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP of 5 cm H2O) to reduce the risk of atelectasis and further lung injury. The intraoperative course was uneventful, with adequate surgical relaxation and hemodynamic stability. Postoperative analgesia was effectively managed using epidural bupivacaine combined with opioids. Adequate pain control is particularly important in such cases, as pain-induced splinting and reduced respiratory effort can lead to atelectasis and postoperative pulmonary complications. The selection of anaesthetic agents and ventilation strategy should be individualized based on the patient’s preoperative pulmonary status. With careful assessment and planning, general anaesthesia can be safely administered even in patients with significant pulmonary compromise.

Conclusion

While most surgical cases follow standard anaesthetic protocols, cases involving chronic pulmonary compromise such as post-tubercular lung fibrosis require tailored perioperative management. In this case, anaesthetic planning accounted for the patient’s altered pulmonary physiology and metabolic derangements. With vigilant intraoperative care and appropriate postoperative pain management, general anaesthesia proved to be a safe and effective approach. A successful outcome, including early extubation and stable recovery, can be achieved through comprehensive, patient-specific anaesthetic planning.

Contributors: GL: manuscript writing, patient management; ST: manuscript editing, patient management. ST will act as a study guarantor. Both authors approved the final version of this manuscript and are responsible for all aspects of this study.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Chauhan A, Parmar Malik P, Dash GC, Solanki H, Chauhan S, Sharma J, et al. The prevalence of tuberculosis infection in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis Indian J Med Res. 2023;157(2-3):135-151.

- Bansal A , Yanamaladoddi VR, Sarvepalli SS, Vemula SL, Aramadaka S, Mannam R, et al. Surviving pulmonary tuberculosis: Navigating the long term respiratory effects. 2023;15(5):e38811.

- Canet J, Mazo V. Postoperative pulmonary complications. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:138-143.

- Kelkar KV. Post-operative pulmonary complications after non-cardiothoracic surgery. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59(9):599-605.

- Ilala TT. Epidural anesthesia for abdominal laparotomy in an obese patient with severe cardiac disease and epilepsy: A rare case report. Journal of Anaesthesia and Clinical Research. 2022;13:1064.

- Block BM, Liu SS, Rowlingson AJ, Cowan AR, Cowan Jr JA, Wu CL. Efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;290(18):2455-2463.