Introduction

Pneumonia in children is considered an invasive disease that should be treated promptly and adequately without delay. Inspite of availability of effective parenteral antibiotic and the pneumococcal conjugated vaccine that cover the most prevalent and dangerous 13 serotypes of streptococcus pneumonia, we still encounter in our practice severe pneumonias that ended up with different types of complications as reported in our case below.

Case Report

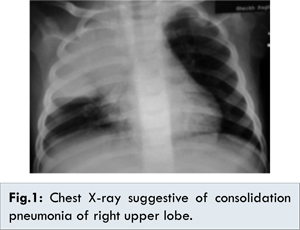

A previously healthy eleven month-old-boy was referred to our hospital for a history of upper respiratory tract infection of minimal symptomatology. This was accompanied by persistent fever of more than 10 days that prompted his primary physician to order a chest X-ray and blood tests which revealed a huge consolidation pneumonia of the right upper lobe [Fig.1], and leukocytosis with increased C-reactive protein. Child was active with no cough, dyspnea, cyanosis or decreased oral intake. But given the family history of death of their four-year old child of pulmonary aspergillosis two years ago, he was admitted for further evaluation and management. His past history was not suggestive of recurrent fever, respiratory symptoms, or tuberculosis exposure and he had received 2 doses of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

He was admitted to regular pediatrics floor and started on intravenous ceftriaxone 100 mg/kg/day and oral azithromycin 10 mg/kg/day. He had normal color and oxygen saturation on room air, leukocytosis: 30,000/mm3; CRP: 280 mg/dL (normal value < 10 mg/dL). After five days of hospitalization he continued to have high grade fever up to 40 degree Celsius and he started to have productive cough but continued to have stable hemodynamic and physical conditions. Further laboratory tests revealed normal immunoglobulin quantification levels and negative PPD test for screening of latent tuberculosis. A second chest X-ray [Fig.2], revealed a new cystic enlarging lesion in the existing consolidation which prompted us to order an urgent contrast CT scan of chest that revealed multiple cystic lesions of thin wall resembling pneumatoceles [Fig.3]. At this time it was decided to broaden our antibiotics regimen to cover the most culprit pathogens such as resistant pneumococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Anaerobes; so he received triple antibiotics course that included intravenous meropenem, vancomycin and metronidazole.

Two days after the new therapeutic regimen, the patient was afebrile with progressive decrease in WBC and CRP. His serial chest X-rays revealed improvement of the consolidation pneumonia and pneumatoceles size, [Fig.3,4]. He was continued on intravenous antibiotics for twenty days and one week oral cefibuten with no reported complications. His follow up chest X-ray at two weeks after discharge, revealed disappearance of pneumatoceles [Fig.5].

Discussion

The incidence of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in children is estimated to be 3% to 4% [

1]. Majority of these patients can be managed effectively by primary care, though the thresholds for referral and admission to hospital in those less than 6 months of age should be lower [

2]. Hospitalization rates for CAP in children range from 9.5% to 42% [1] and the median time to resolution of symptoms in children with oxygen saturations of >85% at the time of admission is 9 days [

3]. Complicated pneumonias in children are most commonly caused by bacterial pathogens, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus [

4], but cultures are reported to be negative in 45% to 89% of cases [

5].

Treatment failure may be due to antibiotic resistance or because CAP is the first presentation of an underlying condition such as cystic fibrosis, immunodeficiency or congenital thoracic malformation (CTM). As seen in our reported case where a typical lobar pneumonia failed to respond to the routinely indicated third generation cephalosporin and had a more severe course of tissue necrosis and cystic lesions that required a more intensive course of broad spectrum antibiotics. He was further investigated to seek any secondary underlying disease that could be the inciting event. The recognized sequelae of pediatric CAP, necrotizing or cavitary pneumonia was first, described in 1994 and has recently been shown to complicate up to 20% of childhood empyemas [

6]. The primary causative pathogen was thought to be S. aureus but S. pneumoniae, [

6], is now the predominant cause, although M. pneumoniae, methicillin-resistant S. aureus and PVL strains of S. aureus [

7] have also been implicated. Diagnosis is usually made on CT. Pneumatoceles are common in necrotizing pneumonia as one-way passage of air into the peripheral airways occurs following necrosis of bronchioles and alveoli [

8]. The majority of pneumatoceles (more than 85%) resolve spontaneously, partially or completely over weeks to months without clinical or radiographic sequelae [

9] as occurred in our reported case which had clinical and radiological evidence of almost complete resolution within six weeks of the primary presentation and antibiotic initiation.

Conclusion

Community acquired pneumonia does not always have a simple course and persistence of fever or deterioration should prompt the treating physician to search an underlying complications or a hidden secondary causes. Contrast CT scan of chest is a helpful diagnostic imaging option that should be performed as soon as possible in case of difficult to treat pneumonias.

References

- Jokinen C, Heiskanen L, Juvonen H, Kallinen S, Karkola K, Korppi M, et al. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in the population of four municipalities in eastern Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:977-988.

- Jadavji T, Law B, Lebel MH, Kennedy WA, Gold R, Wang EE. A practical guide for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric pneumonia. CMAJ. 1997;156:S703-S711.

- Atkinson M, Lakhanpaul M, Smyth AR, Vyas H, Weston V, Stephenson T. Comparison of oral amoxicillin and intravenous benzyl penicillin for community acquired pneumonia in children (PIVOT trial): a multicentre pragmatic randomised controlled equivalence trial. Thorax. 2007;62:1102-1106.

- Kunyoshi V, Cataneo DC, Cataneo AJ. Complicated pneumonias with empyema and/or pneumatocele in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:186-190.

- Tan TQ, Mason EO Jr, Wald ER, Barson WJ, Schutze GE, Bradley JS, et al. Clinical characteristics of children with complicated pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1-6.

- Sawicki GS, Lu FL, Valim C, Cleveland RH, Colin AA. Necrotising pneumonia is an increasingly detected complication of pneumonia in children. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1285-1291.

- Knight GJ, Carman PG. Primary staphylococcal pneumonia in childhood: a review of 69 cases. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992;28:447-450.

- Wilmott RW, Boat TF, Bush A, et al (editors). Kendig and Chernick’s disorders of the respiratory tract in children, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2012.

- Imamoglu M, Cay A, Kosucu P, et al. Pneumatoceles in postpneumonic empyema: An algorithmic approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1111-1117.