Introduction

“Benign maturation” of teratomas were first described in 1969 [

1]. The term growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) was first coined in 1982 by Logothetis et al. in their description of six patients with metastatic mixed germ cell tumors (GCT) [

2]. The incidence of GTS according to various studies is 1.9%-7.6% [

3]. Since 1994, only 13 cases (6 ovarian, 7 testicular) of GTS have been reported from India [

4-

9]. We report a testicular immature teratoma presenting postoperatively, as a retroperitoneal mass refractory to chemotherapy.

Case Report

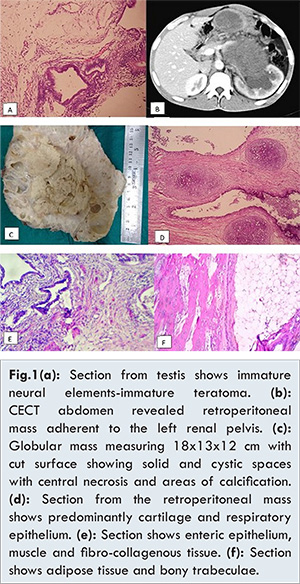

This 21 year old male had been referred to the Urology department for the evaluation of a retroperitoneal mass in November 2015. He had undergone treatment for a painless left-sided testicular swelling at another hospital in November 2014; left orchidectomy had been performed, and post-operatively, he had remained asymptomatic for about 6 months. His ß-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß HCG) and a-fetoprotein (AFP) prior to his surgery in November 2014 were 34.8 mIU/mL (normal <0.8) and 6393 ng/mL (normal <50) respectively. He was finally diagnosed to have an immature testicular teratoma [Fig.1a]. Six months postoperatively, he had developed left-sided abdominal pain of a nonspecific nature. There was no abdominal distension or other gastrointestinal complaints. There was no history of hematuria, decreased urine output or fever. He did not have any other chronic illness.

At the time of his visit, he was conscious and oriented, with pulse rate 82/minute, blood pressure 116/80 mm Hg and respiratory rate 18/minute, with otherwise normal general examination. On systemic examination, respiratory and cardiac systems were normal; a firm mass was palpated in the left hypochondrium, umbilical and left lumbar regions. His penis and right testis were normal, while his left-sided scrotum was empty with a surgical scar. His laboratory investigations were as follows: hemoglobin: 12.1 g/dL, total leukocyte counts: 8.63x109/L, platelets: 324x109/L, random blood sugar: 82 mg/dL, urea: 36 mg/dL and serum creatinine: 1.1 mg/dL. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a large well-defined heterogeneous mass in the retroperitoneum, measuring 16x9x9 cm with specks of calcification. This mass appeared to displace the left kidney superiorly, causing a mild degree of left-sided hydroureteric nephrosis [Fig.1b].

In view of his previous history of immature teratoma, metastasis of immature teratoma was suspected and he was referred to our hospital’s Oncology department. Thereafter, he received four cycles of bleomycin-etoposide-cisplatin (BEP) based chemotherapy between September and November 2015. Post-chemotherapy, his ß-HCG and AFP were 5 mIU/mL and 131.3 ng/mL respectively. Even after chemotherapy, the size of the mass had remained unchanged (both clinical and radiological) and hence he had been referred to the Urology department. Following evaluation, he was planned for tumor excision. Per-operatively, a retroperitoneal mass encasing the lateral border of the renal artery and vein, aorta, small intestine, colon, gonadal vein, ureter, left common iliac artery and psoas fascia was noticed. Tumor excision, left nephrectomy and aortic resection with aortic graft placement was performed. Histopathological evaluation revealed a mature teratoma. He is still under follow up.

Discussion

Testicular tumors constitute 1% of all malignancies in males. Among these, 90% are germ cell tumors; half of these are non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT) [

10]. The usual presentation of GTS is patients with NSGCT, after appropriate chemotherapy and normalization of serum markers, developing metastatic masses [

3]. Theories of GTS include: immature malignant elements destroyed by chemotherapy leaving benign mature elements behind; tumor cell kinetics being altered by chemotherapy and totipotent malignant germ cells transforming into mature benign teratoma; spontaneous and inherent differentiation of malignant cells into benign tissues [

11]. Another reasonable explanation for GTS is “chemotherapeutic reconversion” of immature teratoma cells into mature tissue [

12]. Our patient had a metastatic mass even before chemotherapy but it is also probable that chemotherapy could have also altered the immature elements. Sites for GTS are the retroperitoneum (commonest: 80%), mediastinum, chest, liver, abdomen, sublcavian node, inguinal nodes and the mesentery [

1,

13].

Three criteria are required for diagnosis of GTS: a patient is receiving or has received chemotherapy, previously elevated serum markers (ß-HCG and AFP) become normal, and there is a paradoxical increase in tumor size with absence of immature component [

2]. For primary mediastinal NSGCT, Kesler et al. proposed that the criteria for GTS also include cardiopulmonary deterioration due to compression of vasculature, heart or lungs [

14]. GTS has been commonly reported with the BEP chemotherapy regimen as in our patient [

1].

Serum markers for GTS include AFP, ß-HCG and lactate dehydrogenase [

1]. Radiological exam in GTS reveals masses ranging in sizes between 1 and 25 cm with well circumscribed margins, cystic changes with adipose tissue and calcifications which may be either punctate or curvilinear [

1]. Microscopy shows both solid and cystic components and can comprise cartilaginous elements, epithelium (enteric and respiratory), and neurogenic tissue with undifferentiated spindle cell stroma [

1]. GTS tumors are chemoradiotherapy resistant and the treatment of choice is surgical excision, as in our case. Complications of GTS occur predominantly due to compression of surrounding structures leading to problems such as hydroureteronephrosis and venous stasis. Our patient had tumor adherence to blood vessels and the left kidney. The fate of GTS, studied in a large French cohort includes relapse of GTS or NSGCT, or second malignancies such as sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, PNET, carcinoid and leukemia [

15].

Conclusion

GTS is a rare tumor with very few reports from India in the last 22 years. Pathologists, urologists, gynecologists and oncologists need to be aware to prevent misdiagnosis of recurrence, to institute early surgical resection and carefully follow up patients with immature teratoma for detecting new metastatic tumors.

References

- Gorbatiy V, Spiess PE, Pisters LL. The growing teratoma syndrome: Current review of the literature. Indian J Urol. 2009;25:186-189.

- Logothetis CJ, Samuels ML, Trindade A, Johnson DE. The growing teratoma syndrome. Cancer. 1982;50:1629-1635.

- Boukettaya W, Hochlaf M, Boudagga Z, Ezzairi F, Chabchoub I, Gharbi O, et al. Growing Teratoma Syndrome after Treatment of a Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumor: A Case Report and a Review of Literature. Urol Case Rep. 2014;2:1e3.

- Sengar AR, Kulkarni JN. Growing teratoma syndrome in a post laparoscopic excision of ovarian immature teratoma. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010;21:129-131.

- Hariprasad R, Kumar L, Janga D, Kumar S, Vijayaraghavan M. Growing teratoma syndrome of ovary. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:83-87.

- Panda A, Kandasamy D, Sh C, Jana M. Growing teratoma syndrome of ovary: avoiding a misdiagnosis of tumour recurrence. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:197-198.

- Mir R, Kaul S, Singh VP. Growing teratoma syndrome: Case report and review of literature. Apollo Med. 2014;11:e293-296.

- Ravi R. Growing teratoma syndrome. Urol Int. 1995;55:226-228.

- Tongaonkar HB, Deshmane VH, Dalal AV, Kulkarni JN, Kamat MR. Growing teratoma syndrome. J Surg Oncol. 1994;55:56-60.

- Coscojuela P, Llauger J, Pérez C, Germá J, Castañer E. The growing teratoma syndrome: radiologic findings in four cases. Eur J Radiol. 1991;12:138-140.

- Hong WK, Wittes RE, Hajdu ST, Cvitkovic E, Whitmore WF, Golbey RB. The evolution of mature teratoma from malignant testicular tumors. Cancer. 1977;40:2987-2992.

- DiSaia PJ, Saltz A, Kagan AR, Morrow CP. Chemotherapeutic retroconversion of immature teratoma of the ovary. Obstetr Gynecol. 1977;49:346-350.

- Lorusso D, Malaguti P, Trivellizzi IN, Scambia G. Unusual liver locations of growing teratoma syndrome in ovarian malignant germ cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep. 2011;1:24-25.

- Kesler KA, Patel JB, Kruter LE, Birdas TJ, Rieger KM, Okereke IC, et al. The “growing teratoma syndrome” in primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: criteria based on current practice. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:438-443.

- Andre F, Fizazi K, Culine S, Dros JP, Taupin P, Lhomme C, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome: results of therapy and long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1389-1394.