Introduction

Primary chylous disorder is an abnormality caused by congenital lymphangiectasis with or without thoracic duct obstruction [

1-

4]. Abnormal discharge from skin vesicles around perineum, scrotum, labia, or limbs can impair their quality of life. The rupture of lymphatic vesicles may become port d’entrée for bacteria causing cellulitis or lymphangitis [

5]. In patients with lymphatic damage and lymphangiectasis, lymph fluid may reflux to renal pelvis causing chyluria (urine mixed with lymph fluid) once it got ruptured [

6].

Currently, there are not many literatures discussing chylorrhea in external genitalia, both from diagnosis and treatment perspective. Based on this deficiency, we want to give a case illustration about chylorrea in male external genitalia and how to diagnose and manage it. We hope this experience could give alternatives to patient because this abnormality significantly impairs patient’s quality of life, and self-confidence.

Case Report

A 17 years old urban male patient presented with milky discharge from his scrotal skin and penis since he was 8 years old. The discharge was spontaneous, in copious amount, increased on eating fatty food or on activity, and not related to urination

[Fig.1]. He denied fever, urinary complaints, breathing difficulty, abdominal bloating or swelling in lower limb. There was no preceding history of trauma and previous surgery in genitalia or pelvis area. He reported having lost 10 kg in last 3 years. No history of family or neighbours complaining about disease caused by parasites, such as filariasis, or chylous discharge could be elicited.

Physical examination revealed hemodynamically stable patient with 37 kg body weight and 150 cm body height. Body mass index was 16.4, categorized as malnutrition. No abnormalities were found in thorax and abdominal examination. In external genitalia examination, we found no structural abnormalities in penis and scrotum. No white fluid was discharged when these regions were palpated. Rectal examination showed no inflammation in prostate. There was no urethral discharge with prostate massage.

Laboratory examination showed normal hemoglobin, white blood cell (WBC), and platelet counts. Blood urea, creatinine and lipid profile reports were normal. In urinalysis, we found cloudy urine, with pH of 6, urinary WBC 4-5/high power field, red blood cell 0-1/high power field, and no bacteria. Body fluid analysis from urethral and scrotum discharge was suggestive of scrotum fluid. Rivalta test was positive in accordance with chylous-type fluid. Wauchereria bancrofti antigen analysis from the same fluid was negative. Transrectal ultrasonograpghy showed no abnormalities in both prostate and vesica seminalis. Retrograde uretrocystography showed no contrast extravasation or urethra stenosis. Chest X-ray was normal. We did urethrocystoscopy and there were no stricture or fistula in urethra. The bladder was normal and no discharge was found in both ends of ureter.

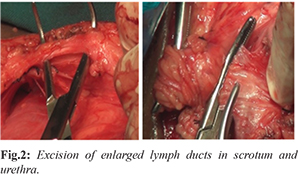

Scrotum and periurethral exploration revealed enlarge lymphatic vessels in scrotum area. There were seven enlarged lymphatic canals in left scrotum

[Fig.2], three enlarged lymphatic canals in right scrotum, and two in periurethral region. Ligations were done in these canals using multifilament absorbable sutures. Scrotum skin was excised entirely. All excised tissues were sent for histopathologic examination.

Povidone iodine was used to identify oozing chylous fluid from lymph nodes around operating area. The white-cloudy colored chylous was easily visible with dark background created by povidone iodine. Operation wound was washed with sterile saline. Designs were made to make flap from skin and subcutaneous tissue on medial side of both thighs. The size of flaps design was customized to the defect made. Flaps then were freed until subcutaneous level and ensured to be tension-free. After the flaps were tension-free and had no resistant for mobilization, both flaps, each from medial side of thigh, were sutured to medial side of the scrotum. All sides of the flaps were sutured using multifilament absorbable 2-0 for subcutaneous and monofilament non-absorbable 2 for skin suturing. Two drains were then set under the base of flaps

[Fig.3]. Surgery took approximately 4 hours, with about 200 ml intraoperative bleeding.

Post-surgery, fixation was done using elastic bandage on both limbs to prevent mobilization. Three days after surgery, the fixation was freed and patient was allowed to do restricted mobilization. Five days after surgery, patient was allowed to sit. Vacuum drains on both thighs were released on day seven after surgery. The sutures in skin were opened two weeks after surgery. Histopathology examination showed tissues with inflammation and no malignancy was found.

All symptoms of scrotal discharge resolved within three month, examination showed healthy surgical wound with well-formed granulation tissue

[Fig.4a]. Our patient was followed up for 3 years after resolution of symptoms

[Fig.4b].

Discussion

Chylorrhea on external genitalia is a rare abnormality. Noel, et al. retrospectively reviewed 35 patients with primary chylous disorder [

7]. Majority of patients from the study complained white discharge during urination (chyluria). However, in our study, patient complained chylous discharge from urethral ends and scrotum since the age of 8 years that was not related to urination. The discharge was also getting heavier with certain food consumption, such as instant noodle or food with flavor enhancement. Although, until today, there is no data about association of preservatives and food flavorings with chylorrhea, in our patient situation, his concern about increasing chylorrhea production related to food intake might have affected his food habits making him undernourished. The other psychological problem that may interfere is low self-esteem due to this abnormality. Spontaneous and continuous chylous discharge not related to urination forced him to use diapers or menstrual pads every day, further decreasing his self-confidence.

His physical and radiologic examination along urethroscopy were normal. His diagnosis was based on chylous fluid analysis that came from external genitalia. According to Noel et al, further examination may include CT-scan or MRI, lymphoscintigraphy, or lymphangiography [

7]. Moreover, we have limitation to do lymphatic imaging. Based on this consideration, we didn’t do further examinations stated by Noel et al. We did trans-rectal ultrasound to see obstruction or inflammatory signs in vesical seminalis causing urethral discharge. Urethrographic and urethroscopic examination were performed to see possible fistula or inflammation from lymphatic tissue along urethra and bladder that cause chylous fluid secretion.

We found lymphatic duct enlargement in some places when the scrotum and periurethral areas were explored. Generally, normal lymphatic duct is not visible macroscopically and hard to differentiate from nearby tissues. In this patient, clear-colored ducts with cloudy-white fluid that seeps from them were macroscopically found. Enlarge lymphatic ducts were then ligated and cut. Intraoperative evaluation can be done using povidone iodine as marker for remaining lymphatic ducts that produce chylous fluid. Povidone iodine gives dark background that will make white cloudy fluid be easier visible. All scrotum skin was excised because all lymphatic ducts ends are located on it. Defect closure was done using flap from cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue from both thighs after it was ensured no more lymphatic duct produce chylous. Flap was made using rotational flap to get better vessels supply compared to skin graft.

Conclusion

External genitalia chylorrhea is a rare lymphatic abnormality that may impair patient’s quality of life. Excision of enlarged lymphatic ducts can reduce patient’s complaint. Defect closure after procedure using rotational flap from both thighs may be effective solution and give good results.

Contributors: All authors have contributed to patient management and manuscript writing.

Funding: None;

Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Kinmonth JB, Cox SJ. Protein-losing enteropathy in lymphoedema. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;16:111-114.

- Servelle M. Congenital malformation of the lymphatics of the small intestine.J Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;32:159-165.

- Servelle M. Surgical treatment of lymphedema: a report on 652 cases. Surgery. 1987;101:485-495.

- Browse NL, Wilson NM, Russo F, al-Hassan H, Allen DR . Aetiology and treatment of chylous ascites. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1145-1150.

- Gloviczki P, Noel AA. Lymphatic reconstructions. Rutherford RB. Rutherford’s vascular surgery. 5th ed. 2000. Philadelphia : WB Saunders Company. pp. 2159-2174.

- Schield PN, Cox L, Mahony DT. Anatomic demonstration of the mechanism of chyluria by lymphangiography, with successful surgical treatment. New Engl J Med. 1966;274:1495-1497.

- Noel AA, Gloviczki P, Bender CE, Whitley D, Stanson AW, Deschamps C, et al. Treatment of symptomatic primary chylous. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2001;34:785-791.