6go6ckt5b8|3000F7576AC3|Tab_Articles|Fulltext|0xf1ff68d4250000006307000001000a00

6go6ckt5b5idvals|900

6go6ckt5b5|2000F757Tab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Chronic constrictive pericarditis is a chronic inflammatory process that causes fibrous thickening of the pericardium. As a result, diastolic filling of the heart is restricted causing reduced venous return and cardiac output [

1-

3]. The etiological factors include infections, idiopathic chronic pericarditis, post-cardiac surgery, mediastinal radiotherapy. The pericarditis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common cause in endemic area [

2-

4]. Tuberculous pericarditis still now remain as a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the medical practitioners even in endemic area because of its diagnostic dilemma.

Case Report

A 25-year-old Vietnamese, non-smoker, non-alcoholic, non-diabetic, normotensive salesman from a province in Vietnam presented with dyspnea on exertion, ankle edema, puffiness of face and abdominal distension, non-productive cough, weight loss of about 14 kg in two and half months. This was accompanied by night sweats and evening fever for about a week. The patient was previously healthy, referring no prior cardiac surgery, chest radiotherapy or tuberculosis. General examination revealed generalized pitting edema, swelling of face, good build and nutritional status, elevated jugular venous pressure, Kussmaul’s sign [Videoclip 1]. His vitals were blood pressure: 125/85 mmHg, pulse: 85/min, respiratory rate: 20/min, temperature: 98.4ºF, SpO2: 96% (air room). Cardiovascular system examination revealed no visible apex beat or any other pulsation, no palpable apex beat, no parasternal heave, no palpable P2. First and second heart sound were soft in all the areas of precordium, a high pitched early diastolic pericardial knock over the left sternal border [Audioclip 1]. Examination of abdomen revealed distended abdomen, shifting dullness positive, bowel sound present, and liver 3 cm from right costal margin in mid-clavicular line. After hospitalization and taking treatment like diuretics (furosemide and spironolactone), anti-tussive (dextromethorphan) and following few advices e.g. restricted fluid intake slight improvement was seen.

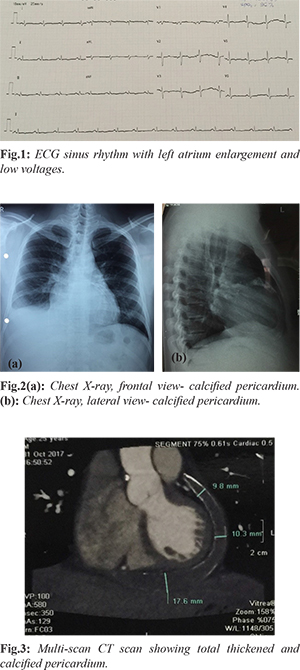

His hematological and biochemical profile showed white blood cell: 6.2 K/µL (4.6-10.2 K/µL) with high monocyte: 15% (0-12%), hemoglobin: 14.6 g/dL, serum creatinine: 1.168 mg/dL, modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD): 76 ml/min/1.73m2, C-reactive protein: 25.44 mg/L (<5 mg/L). NT-pro-BNP: 592 pg/mL (<75 years: = 125 pg/ml; =75 years: =450 pg/mL), TSH: 4.76 µIU/mL (0.32-5 µIU/mL). Mycobacterium tuberculosis Quantiferon test and anti ds-DNA were negative. Electrocardiogarphy showed sinus rhythm with left atrium enlargement and low voltages [Fig.1]. Chest X-ray frontal and lateral views showed calcified pericardium. Cardiac shadow was within normal limits [Fig.2]. Mild ascites and congestive hepatomegaly were noted on ultrasonography. Echocardiography revealed thickened pericardium (5 mm), mild to moderate pericardial effusion (12 mm), left atrium enlargement (LA= 48 mm), respiratory variation of the mitral peak E velocity of 29%, ejection fraction: 55%, PASP: 20 mmHg. 640 slices-cardiac multi-slice computed tomography showed left and right atrium enlargement, total thickened and calcified pericardium, normal coronary arteries with moderate right pleural effusion [Fig.3]. Pleural fluid analysis showed transudate according to Light’s criteria: effusion protein (29.7 g/L)/serum protein (79.7 g/L) ratio less than 0.5; effusion lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (91 U/L)/serum LDH (277 U/L) ratio less than 0.6; effusion LDH level (91 U/L) less than two-thirds the upper limit of the laboratory's reference range of serum LDH (248 U/L); adenosine deaminase: 4.21 U/L (<30 U/L). Constrictive pericarditis was diagnosed on basis of history, clinical findings and investigations. After 42 days of admission, pericardiectomy was done by standard median sternotomy. In some areas, pericardium was stony hard and was very difficult to cut by scissor. Pericardium was sent for histopathological report. Straw colour fluid and thick caseous materials present in the pericardial cavity was sent for microbial, biochemical study. Report was positive in favour of tuberculosis. Histopathological report of removed pericardium showed dense infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells and granulomatous inflammation consistent with tuberculous pericarditis. After operation patient’s post-operative course was uneventful with improvement of heart function. Pre-operatively, the patient was in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III-IV. During the 1st post-operative week, our patient’s functional capacity improved dramatically, and he was in NYHA functional class I-II.

Discussion

The diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis based on 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases [

5,

6] consist of the association of signs and symptoms of right heart failure: ankle edema, puffiness of face and abdominal distension, elevated jugular venous pressure, liver enlargement and impaired diastolic filling due to pericardial constriction (Kussmaul’s sign, pericardial knock) by one or more imaging methods including chest X-ray showing calcified pericardium. The detection of pericardial calcification on radiography is important for definitive diagnosis [

5]. Echocardiography shows thickened pericardium (5 mm), respiratory variation of the mitral peak E velocity of >25%; cardiac MSCT: pericardial thickness and calcification.

The incidence of post-tuberculous constrictive pericarditis has always been comparatively low in the developed world as compared to the developing world. In sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, tuberculosis continues to be the most common cause of constrictive pericarditis [

3,

6]. This patient lived in endemic areas of tuberculosis (Vietnam). Based on 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases score of 7 suggested tuberculous pericarditis for people living in endemic area [

6]. This diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological report.

The dissociation of intra-thoracic and intra-cardiac pressures and enhanced ventricular interdependence are hallmark of restrictive cardiomyopathy which is differential diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis [

6]. Modern trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) techniques, cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging help in establishing a diagnosis in majority of cases [

6]. Surgical and medical treatment are two therapeutic options of treatment of constrictive pericarditis. Between these two options, pericardiectomy is considered as the only definitive treatment [

3,

6]. In our case after symptomatic improvement on medical therapy, patient underwent definitive treatment pericardiectomy followed by anti-tubercular chemotherapy for another six months.

Conclusion

A high index of suspicion for constrictive pericarditis is required in endemic areas for patients presenting with right heart failure. The mainstay of treatment of chronic constrictive tuberculous pericarditis is pericardiectomy and anti-tubercular therapy.

Contributors: HTP wrote the manuscript, did literature search, involved in patient management, and approved the final version of this article. He will act as guarantor of the study.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

References

- Liu YW, Tsui HR, Li WH, Lin LJ, Chen JH. Tuberculous constrictive pericarditis with concurrent active pulmonary tuberculosis infection: a case report. Cases Journal. 2009;2:1-5.

- Nicholas TK, Eugn HB, Donald BD, Frank LH, Robert BK. Pericardial disease In: Kirklin/Barratt-Boyes Cardiac susgery.3rd ed. NewYork:Churchill Livingstone; 2003, pp. 1779-1793.

- Basak RK, Aftabuddin M, Adhikary AB, Khan OS, Rahman KMA. A case report of tubercular constrictive pericarditis. University Heart Journal. 2014;10:42-44.

- Chhina D, Gupta R, Mohan B. Early diagnosis in an unusual presentation of tubercular pericarditis - A case report. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3:161-163.

- Yetkin U, IIhan G, Calli AO, Yesil M, Gurbuz A. Severe calcific chronic constrictive tuberculous pericarditis. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2008;35:224-225.

- 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. European Heart Journal. 2015;36:2921-2964.