Introduction

Giant cell reparative granuloma was first described by Jaffe in 1953 [

1]. This lesion occurs most commonly in maxilla and mandible [

2], rare cases have been reported in the bones of skull, including the orbit [

3,

4], paranasal sinuses [

5], cranial vault [

6], temporal [

7,

8], sphenoid [

9] and occipital [

10] bones.

Case Report

A 20-year-old woman presented with protrusion of her left eye with reduced vision. No history of trauma was present. A complete physical examination revealed no abnormality except exophthalmia and chemosis in left eye. Hemogram, serum free calcium and alkaline phosphotase were within normal limits.

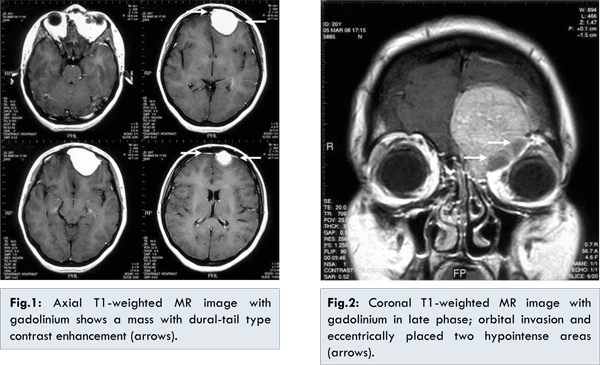

Axial T1-weighted MR image with gadolinium (TR: 582 ms, TE: 10 ms, slice thickness: 5.5 mm) showed a spherical mass with smooth margin and homogenous contrast enhancement in the left superior orbital region, left frontal and ethmoidal sinuses. Dural-tail type contrast enhancement which is a typical finding of meningioma was also seen in this lesion [Fig.1]. Indentation to the left frontal lobe, causing a shift of midline to right hemisphere, was observed. T1 imaging showed isointense lesion in grey matter of brain, while it was moderately hyperintense on T2 image. Coronal T1-weighted MR image with gadolinium in late phase (TR: 709 ms, TE: 200 ms, slice thickness: 3.5 mm) showed orbital bone and fat tissue involvement of the mass more clearly. Contrast enhancement was diffusely diminished due to late phase. Superior oblique muscle was compressed. Eccentrically placed two hypointense areas were visible in the orbital neighboring of the mass reflecting bone formation and fibrous tissue [Fig.2].

The patient underwent bi-frontal craniotomy with total excision of the mass. The histopathologic examination revealed a lesion composed of randomly distributed multinuclear giant cells in a background of cellular fibroblastic stroma [Fig.3]. There was no atypia or atypical mitotic figures. Cystic spaces, hemosiderin deposition and reactive osteoid formation were also seen. Immunohistochemistry was performed by using p63 antibody (Neomarkers, 1/100), no immunolabelling was detected. Eleven months after surgery, MR imaging showed no recurrence and the patient had no complaints.

Discussion

GCRG is a non-neoplastic, reactive fibro-osseous proliferation due to an inflammatory process following a trauma or an infection [

2,

5,

8,

10,

11]. GCRG occur most commonly in women before the age of 30 [

11,

12]. In head and neck, GCRG usually involve the mandible and maxilla [

2,

7,

13]. Cases with the involvement of the orbit is rare [

3,

4]. Sood et al. reported the first case in orbit in 1967 [

14]. Histologically, GCRG is composed of multinucleated giant cells unevenly distributed within a non-neoplastic fibrous stroma, admixed with areas of hemorrhage and reactive osteoid formation [

2,

9,

10,

12].

The differential diagnosis of GCRG includes the other giant cell lesions. These lesions are true giant cell tumor (GCT), aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) and brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism [

2,

11,

13]. The most important one to distinguish from GCRG is GCT because of their different biological behaviour, prognosis and treatment [

2,

8,

10]. Unlike GCT, no metastasis or malignant transformation is observed in GCRG and surgery alone is the choice of treatment [

2,

10,

13]. Recurrence in GCRG may be observed because of incomplete resection [

13]. The clinical data, location and histopathological appearance must be considered together in the differentiation of these two lesions. As in our case, GCRG occurs in a younger population than GCT [

11,

12]. GCRG occurs most commonly in maxilla and mandible while GCT usually occurs in the epiphyses of long bones [

2,

12]. Histologically, both lesions have multinuclear giant cells. The giant cells in GCRG have fewer nuclei and are irregularly distributed while those in GCT are larger in size with a greater number of nuclei and are evenly distributed. The presence of reactive osteoid, hemorrhage, hemosiderin and fibrosis favors GCRG while the presence of necrosis and high mitotic rate favors GCT [

2,

8,

9,

10,

15]. Dickson et al. reported that p63 is a useful biomarker to differentiate GCT from GCRG. As in our case, no p63 immunoreactivity was detected in GCRG while in all cases of GCT p63 expression was identified [

16].

ABC affecting the craniofacial bones may histologically be mistaken for GCRG. Although ABC was characterized by a cystic rapidly enlarging lesion and histologically fibroblastic proliferation with giant cells and stromal hemorrhage similar to those seen in GCRG, ABC has large blood-filled spaces that GCRG doesn’t have. In any event the diagnosis of GCRG depend not only microscopic examination of the lesion, but also on its location, especially whether it occurs in the long bones or the vertebra. The distinction of these two entities is more complicated when an otherwise histologically typical GCRG is secondarily involved by ABC [

17,

18].

Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism is histologically similar with GCRG. Normal serum calcium, phosphorus and parathormone levels favors the diagnose of GCRG [

4,

7]. In MR findings of the previously reported GCRG cases always had a hypointense component reflecting fibrous tissue and bone formation [

7] as in our case. Dural tail sign that is typical finding for meningioma [

18] was also seen in our case. Felsberg et al. also reported a frontoethmoidal GCRG with dural tail sign in MR images due to thickening of the dura [

19].

Treatment of GCRG is surgical excision and does not require radiation therapy. GCRG has a good prognosis, no cases of metastases or malignant transformation have been reported [

2,

10,

13]. The incidence of recurrence is 12%-16% because of incomplete excision [

2]. For recurrent cases anti-angiogenic therapy is used, Collins reported successful results in the treatment of GCRG [

20]. Alternative treatments for GCRG are systemic injections of calcitonin and intralesional injections of corticosteroids [

21,

22].

In conclusion, GCRG is a benign bone lesion that may sometimes be difficult to distinguish histologically from GCT which has a different biological behaviour and treatment. In such cases p63 immunolabelling may be helpful in differential diagnosis. Radiology do not differ these two lesions. The presence of the dural tail that is typical sign of meningioma in MR makes our case more confusing preoperatively.

References

- Jaffe HL. Giant cell reparative granuloma, traumatic bone cyst and fibrous (fibro-osseous) dysplasia of the jaw bones. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1953;6:159-175.

- Williams JC, Thorell WE, Treves JS. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the petrous temporal bone: A case report and literature review. Skull Base Surg. 2000;10(2):89-93.

- Mercado GV, Shields CL, Gunduz K.Giant cell reparative granuloma of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:485-487.

- Pherwani AA, Brooker D, Lacey B. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the orbit. Ophthal Plast Recostr Surg. 2005;21(6):463-465.

- Plontke SK, Adler CP, Gawlowski J. Recurrent giant cell reparative granuloma of the skull base and the paranasal sinuses presenting with acute one-sided blindness. Skull Base Surg. 2000;10(1):9-17.

- Uchino A, Kato A, Yonemitsu N.Giant cell reparative granuloma of the cranial vault. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1791-1793.

- Reis C, Lopes JM, Carneiro E. Temporal giant cell reparative granuloma: A reappraisal of pathology and imaging features. Am J Neuroradiol.2006;27:1660-1662.

- Tian XF, Li TJ, Yu SF. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the temporal bone. Arch Pathol Lab Med: 2003;127:1217-1220.

- Aralasmak A, Aygun N, Westra WH, Yousem DM. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the sphenoid bone. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol.2006;27:1675-1677.

- Santoz-Briz A, Lobato RD, Ramos A. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the occipital bone. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:151-155.

- Magu S, Mathur SK, Gulati SP. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the base of the skull presenting as a parapharingeal mass. Neurol India. 2003;51:260-262.

- Morris JM, Lane JI, Witte RJ, Thompson DM. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the nasal cavity. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1263-1265.

- Arda HN, Karakus MF, Ozcan M. Giant cell reparative granuloma originating from the ethmoid sinus. Int J Ped Otorhinolarynology. 2003;67:83-87.

- Sood GC, Malik SRK, Gupta K, Kakar PK. Reparative granuloma of the orbit causing unilateral proptosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967;63:524-527.

- Auclair PL, Cuenin P, Kratochvil FJ. A clinical and histomorphologic comparision of the central giant cell granuloma and the giant cell tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:197-208.

- Dickson BC, Li S, Wunder JS. Giant cell tumor of bone express p63. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:369-375.

- Huvos AG. Bone Tumors. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1991:469-477.

- Goldsher D, Litt AW, Pinto RS, et al. Dural tail associated with meningiomas on Gd-DTPA-enhanced MR images: characteristics, differential diagnostic value, and possible implications for treatment. Radiology. 1990;176:447-450.

- Felsberg GJ, Tien RD, McLendon RE. Frontoethmoidal giant cell reparative granuloma. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1551-1554.

- Collins A. Experience with anti-angiogenic therapy of giant cell granuloma of the facial bones. Ann R Aust Coll Dent Surg. 2000;15:170-175.

- Harris M. Central giant cell granulomas of the jaws regress with calcitonin therapy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;2:89-94.

- Carlos R, Sedano O. Intralesional corticosteroids as an alternative treatment for central giant cell granuloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 200293:161-166.